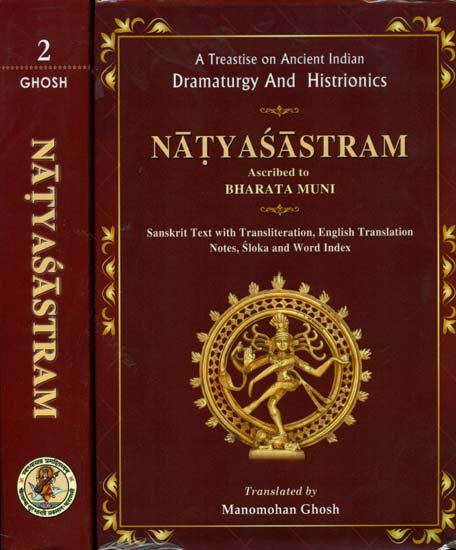

Natyashastra (English)

by Bharata-muni | 1951 | 240,273 words | ISBN-13: 9789385005831

The English translation of the Natyashastra, a Sanskrit work on drama, performing arts, theater, dance, music and various other topics. The word natyashastra also refers to a global category of literature encompassing this ancient Indian tradition of dramatic performance. The authorship of this work dates back to as far as at least the 1st millenn...

Part 1 - The Present Work

1. General History of the Study

Since the West came to know of the Sanskrit literature through William Jones’s translation of the Śakuntalā[1], the nature and origin of the ancient Indian theatre have always interested scholars, especially the Sanskritists, all over the world. H. H. Wilson who published in 1826 the first volume of his famous work on the subject[2] deplored that the Nātyaśāstra, mentioned and quoted in several commentaries and other works, had been lost for ever[3]. F. Hall who published in 1865 his edition of the Daśarūpa[4], a medieval work on the Hindu dramaturgy, did not see any Ms. of the Nāṭyaśāstra till his work had greatly advanced[5]. And for the time being he printed the relevant chapters of the Nāṭyaśāstra as an appendix to his Daśarūpa. Later on he undertook to critically edit the Ms. of the Nāṭyaśāstra he acquired; but this venture was subsequently given up, due perhaps to an insufficiency of materials which consisted of one unique Ms. full of numerous lacunae.[6] But even if the work could not be brought out by Hall, his very important discovery soon helped others to trace similar Mss. elsewhere. And in 1874 Heymann, a German scholar, published on the basis of Mss. discovered up till that date a valuable article[7] on the contents of the Nāṭyaśāstra. This seems to have been instrumental in attracting competent scholars to the study of this very important text. The French Sanskritist P. Regnaud published in 1880 chapter XVII[8] and in 1884 chapter XV (in part) and the chapter XVI[9] of the Nāṭyaśāstra. This was soon followed by his publication of chapters VI and VII in 1884.[10] And J. Grosset another French scholar and a pupil of Regnaud, published later on (in 1888) chapter XXVIII[11] of the Nāṭyaśāstra which treated of the general theory of Hindu music.

But the different chapters of the work and studies on them, which were published up till 1888, though very helpful for the understanding of some aspects of the ancient Indian dramatic works cannot be said to have thrown any considerable light on the exact nature of the ancient Hindu plays, especially the manner of their production on the stage. Sylvain Lévi’s Théatre indien (1890) in which he discussed comprehensively the contribution of his predecessors in the field and added to it greatly by his own researches, made unfortunately no great progress in this specific direction. Though he had access to three more or less complete Mss. of the Nāṭyaśāstra, Lévi does not seem to have made any serious attempt to make a close study of the entire work except its chapters XVII-XX (XVIII-XXII of our text) and XXXIV. The reason for his relative indifference to the contents of the major portion (nearly nine-tenths) of the work, seem to be principally the corrupt nature of his Ms. materials, like his predecessors, Lévi paid greater attention to the study of the literary form of the ancient Hindu plays with the difference that he utilised for the first time the relevant chapters of the Nāṭyaśāstra,[12] to check the accuracy of the statements of later writers on the subject like Dhanañjaya[13] and Viśvanātha[14] who professed their dependence on the Nāṭyaśāstra. But whatever may be the drawback of Lévis magnificient work, it did an excellent service to the history of ancient Indian drama by focussing the attention of scholars on the great importance of the Nāṭyaśāstra. Almost simultaneously two Sanskritists in India as well as one in the West were planning its publication. In 1894 Pandits Shivadatta and Kashinath Pandurang Parab published from Bombay the original Sanskrit text of the work.[15] This was followed in 1898 by J. Grosset’s[16] critical edition of its chapters I-XIV based on all the Mss. available up till that date.

Though nearly half a century has passed after the publication of Grosset’s incomplete edition of the Nāṭyaśāstra, it still remains one of the best specimens of modern Western scholarship, and though in the light of the new materials available, it is possible now-a-days to improve upon his readings in a few places, Grosset’s work will surely remain for a long time a landmark in the history of the study of this important text. It is a pity that this very excellent work remains unfinished. But a fact equally deplorable is that it failed to attract sufficient attention of scholars interested in the subject. Incomplete though it was, it nevertheless contained a good portion of the rules regarding the presentation of plays on the stage, and included valuable data on the origin and nature of the ancient Indian drama, but no one seems to have subjected it to the searching study it deserved. Whoever wrote on Hindu plays after Lévi depended more on his work than on the Nāṭyaśāstra itself, even when this was available (at least in a substantial part) in a critical edition. It may very legitimately be assumed that the reasons which conspired to render the Nāṭyaśāstra rather unattractive included among other things, the difficulty of this text which was not yet illuminated by a commentary.

Discovery in the early years of the present century of a major portion of a commentary of the Nāṭyaśāstra by the Kashmirian Abhinavagupta[17] seemed to give, however, a new impetus to the study of the work. And it appeared for the time being that the Nāṭyaśāstra would yield more secrets treasured in the body of its difficult text. But the first volume of the Baroda edition of the work (ch. I-VII)[18] including Abhinava’s commentary, disillusioned the expectant scholars. Apart from the question of the merit of this commentary and its relation to the available versions of the Nāṭyaśāstra, it suffered from a very faulty transmission of the text. Not only did it contain numerous lacunae, but quite a number of its passages were not liable to any definite interpretation due to their obviously vitiated nature. Of this latter condition the learned editor of the commentary says, “the originals are so incorrect that a scholar friend of mine is probably justified in saying that even if Abhinavagupta descended from the Heaven and seen the Mss. he would not easily restore his original reading. It is in fact an impenetrable jungle through which a rough path now has been traced”. The textual condition of Abhinava’s commentary on chapters VIII-XVIII (VIII-XX of our text) published in 1934[19] was not appreciably better.

But whatever may be the real value of the commentary, the two volumes of the Nāṭyaśāstra published from Baroda, which were avowedly to give the text supposed to have been taken by Abhinava as the basis of his work, presented also considerable new and valuable materials in the shape of variant readings collated from numerous Mss. of the text as well as from the commentary. These sometimes throw new light on the contents of Nāṭyaśāstra. A study of these together with a new and more or less complete (though uncritical) text of the work published from Benares in 1929[20] would, it is hoped, bo considered a desideratum by persons interested in the ancient Indian drama. The present work has been the result of such a study, and in it has been given for the first time a complete annotated translation of the major portion of the Nāṭyaśāstra based on a text reconstructed by the author.[21]

2. The Basic Text

The text of the Nāṭyaśāstra as we have seen is not available in a complete critical edition, and Joanny Grosset’s text (Paris-Lyons, 1898) does not go beyond ch. XIV. Hence the translator had to prepare a critical edition of the remaining chapters before taking up the translation.[22] For this he depended principally upon Ramakrishna Kavi’s incomplete edition (Baroda, 1926, 1934) running up to ch. XVIII (our XX) and including Abhinava’s commentary, as well as the Nirnayasagar and Chowkhamba editions (the first, Bombay 1894, and the second, Benares, 1929). As the text of the Nāṭyaśāstra has been available in two distinct recensions, selection of readings involved some difficulty. After the most careful consideration, the translator has thought it prudent to adopt readings from both the recensions, whenever such was felt necessary from the context or for the sake of coherence, and these have been mentioned in the footnotes. But no serious objection may be made against this rather unorthodox procedure, for A. A. Macdonell in his critical text of the Bṛhaddevatā (Cambridge, Mass. 1904) has actually worked in this manner, and J. Grosset too in his edition does not give unqualified preference to any racension and confesses that due to conditions peculiar to the Nāṭyaśāstra his text has “un caractere largement éclectique” (Introduction, p. xxv) and he further says “nous n’avions pas l’ambition chimérique de tendre a la reconstitution du Bharata primitif... (loc. cit.)”. Conditions do not seem to have changed much since then.

3. Translation

Though the translation has been made literal as far as possible except that the stock words and phrases introduced to fill up incomplete lines have been mostly omitted, it has been found necessary to add a number of of explanatory words [enclosed in rectangular brackets] in order to bring out properly the exact meaning of the condensed Sanskrit original. Technical terms have often been repeated (within curved brackets) in the translation in their basic form, especially where they are explained or defined. In cases where the technical terms could not be literally rendered into English they were treated in two different ways: (1) they were given in romanised form with initial capital letters e.g. Bhāṇa and Vīthī (XX. 107-108, 112-113), Nyāya (XXII. 17-18) etc. (2) Words given as translation have been adopted with a view to indicating as far as possible the exact significance of the original, e.g. State (bhāva) Sentiment (rasa), VI. 33-34. Discovery (prāpti), Persuasion (siddhi), Parallelism (udāharaṇa) (XVII. 1), Prominant Point (bindu), Plot (vastu) (XX.15) etc: Lest these should be taken in their usual English sense they are distinguished by initial capital letters. Constantly occuring optative verbal forms have been mostly ignored. Such verbs as kuryāt and bhavet etc, have frequently been rendered by simple ‘is’ or a similar indicative form. And nouns used in singular number for the sake of metre have been silently rendered by those in plural number and vice versa, when such was considered necessary from the context.

4. Notes to the Traslation

Notes added to this volumes fall generally into three categories, (a) Text-critical. As the basic text is not going to be published immediately, it has been considered necessary to record variant readings. For obvious reasons variants which in the author’s opinion are less important have not been generally recorded, (b) Explanatory. These include among other things references to different works on allied subjects and occasional short extracts from the same. Abhinavagupta’s commentary naturally occupies a prominent place among such works, and it has very often been quoted and referred to. But this does not mean that the worth of this work should be unduly exaggerated.[23] (c) Materials for Comparative Study. A very old text like the Nāṭyaśāstra not illuminated by anything like a complete and lucid commentary, should naturally be studied in comparison with works treating similar topics directly or indirectly. Hence such materials have been carefully collated as far as the resources at the author’s disposal permitted.

But even when supplied with these notes, readers of this translation may have some difficulty in reconstructing from the work written in difuse manner the picture of the ancient Indian drama in its theatrical as well as literary form, as it existed in the hoary antiquity. To give them some help the theory and practice of the ancient Hindu drama has been briefly discussed below together with other relevant matters.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Sacontalā, or the Fatal Ring. Translated from the original Sanskrit and Pracrita, Calcutta 1789.

[2]:

H. H. Wilson, Select Specimens of the Theatre of the Hindus (3 vols), Calcutta. 1826-1827.

[3]:

Wilson, p. 37. Grosset, Introduction, p. iij.

[4]:

The Daśarūpa by Dhananjaya (Bibliotheca Indica), Calcutta, 1861-1865.

[5]:

Grosset, Introduction, v. iij.

[6]:

See note 5 above.

[7]:

Ueber Bharata’s Naṭyaśāstram in Nachrichten von der Koeniglischen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften, Goetingen 1874, pp. 86 ff. Ref, Grosset, Introduction p x; ID. pp 2-3.

[8]:

Le dix-septieme chapitre du Bhāratīya-naṭyaśātra. Annales du Musee Guimet; Tome, l. 1880, pp. 85 ff.

[9]:

La metrique de Bharata, texte Sanscrit de deux chapitres du Nāṭyaśāstra public pour premier fois et suivi d’une, interpretation francaise, Annales due Musee Guimet, Tome, II, 1884, pp. 65 ff.

[10]:

Rhetorique sanscrite, Paris, 1814.

[11]:

Contribution a l'étude de la musique hindou, Lyons, 1888.

[12]:

Chapters XVII-XX (XVIII-XXII of our text).

[13]:

The author of the Dasarūpa. See above note 4.

[14]:

The author of the Sāhityadarpaṇa. See below.

[15]:

Śrī Bharatamuni-praṇītam, Nāṭyaśāstram, (Karyamala, 42) Bombay, 1894.

[16]:

Treats du Bharata sur le Theatre. Tex to sanscrit, Edition critique. Tome 1. Partie, 1. (Annales de I’Universite de Lyons, Fasc. 40, 1898)

[17]:

Dr. S. K. De seems to be the first in announcing the existence of a more or less complete Ms. of Abhinava’s commentary, and in recommending its publication. See Skt, Poetics, Vol I. pp. 120-121.

[18]:

Nāṭyaśāstra with the commentary of Abhinavagupta. Edited with a preface, Appendix and Index by Ramakrishna Kavi. Vol I, Baroda 1926.

[19]:

Nāṭyaśāstra with the commentary of Abhinavagupta. Edited with an Introduction and Index by M. Ramakrishna Kavi. Vol, II, Baroda, 1934.

[20]:

Śrī-Bharatmuni-praṇītam Nāṭyaśāstram. (Kashi-Sanskrit Series), Benares, 1929.

[21]:

This edition will be published later on. The following chapters of the NŚ. have been translated into French: ch XIV and XV (our XV and XVI) Vagabhinaya by P. Regnaud in his Metrique du Bharata; see note 8 above, ch. XVII (our XVIII) Phasavidhana by Luigia Ni?ti-Dolci in her Les Grammairiens Prakrit, This has been partially (1-24) translated into English by the present writer in his Date of the Bharata-Nāṭyaśāstra, See JDL, 1930, pp. 73f. Chapter XXVIII by J. Grosset in his Contribution a l'étude de la musique hindou; see note 10 above. Besides these, ch, XXVIII by B. Breoler in his Grund-elemente der alt-indischen Musik nach dem Bhāratīya-nāṭyaśāstra. Bonn. 1922, and ch. IV by B. V. N. Naidu, P. S. Naidu and O.V.R. Pantlu in the Tāṇḍavalakṣaṇam, Madras, 1936 and chapters I-III translated into Bengali by the late Pandit Asokenath Bhattacharyya in the Vasumati, 1352 BS.

[22]:

???

[23]:

See M, Ghosh, “The NŚ. and the Abhinavabhāratī” in IHQ vol. X, 1934, p p. 161ff.