The Matsya Purana (critical study)

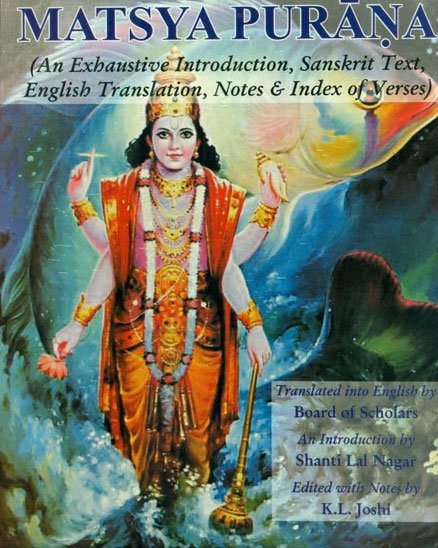

by Kushal Kalita | 2018 | 74,766 words | ISBN-13: 9788171103058

This page relates ‘concept of Vrata’ of the English study on the Matsya-purana: a Sanskrit text preserving ancient Indian traditions and legends written in over 14,000 metrical verses. In this study, the background and content of the Matsyapurana is outlined against the cultural history of ancient India in terms of religion, politics, geography and architectural aspects. It shows how the encyclopedic character causes the text to deal with almost all the aspects of human civilization.

Part 4 - The concept of Vrata

As mentioned earlier the importance of sacrificial system prevailing in the Vedic age diminished with the passing time due to its rigidity and the vratas, upavāsas, śrāddhas, prāyaścittas, dānas, dīkṣās etc. took its place in Purāṇic age. All kinds of people can participate in these austerities which Vedic yajña restricted within a group of people only. The Purāṇas are repositories of such religious rites and customs. Among the religious rites described in the Purāṇas vratas occupy a very important place which is testified by the large numbers of vratas enjoined here.

The term vrata means will, obedience, conduct or custom. It also denotes religious vow or practice, any pious observance, meritorious act of devotion or austerity, any vow or firm purpose, resolve to practice of always eating the same food, feeding only on milk etc.[1]

P. V. Kane in his History of Dharmaśāstra derives the term vrata from the root vṛ (to choose or will) with the suffix ta. He says,

“Therefore, when the word vrata is derived from 'vṛ' with the suffix 'ta', the meaning of vrata can be ‘what is willed’or simply ‘will’.”[2]

This term is used in the sense of law or ordinance as the will of a person who has authority is obeyed by others as law. People generally believe that the gods have laid down certain rules and duties to be followed by them. When commands are obeyed or duties are performed in the same way for long, they become the patterns of obligations and thus it means customs or practices.

The vratas are found treated in the Vedas, Brāhmaṇas, epics, Dharmaśāstras, Sūtras and Purāṇas. In the Ṛgveda, vrata is used to mean divine ordinance or ethical patterns of conduct.[3] Again in the Ṛgveda, Agni is said to be the vratapā which means the protector of vrata.[4] The Atharvaveda uses the term vrata as ordinances of gods.[5]

Yāskācārya has given two meanings of vrata, viz.,

- religious observance or restrictions as to food and behaviour and

- special food prescribed for a person engaged in religious rites.[6]

In the sūtras of Pāṇini also these meanings of the term vrata are expressed clearly.[7] In the Mahābhārata, the word vrata is used to mean mainly a religious undertaking or vow in which one has to follow certain restrictions on food or on general behaviour.[8] Śabara in his Bhāṣya on Mīmāṃsādarśana stated that vrata means an activity of mind which is a resolve in the form of ‘I shall not do this’.[9] The Mitākṣarā on Yājñavalkyasmṛti indicates that vrata is a mental resolve to do something or refrain from doing something.[10]

Thus, the word vrata has different etymological meanings, yet it is mainly used as a religious undertaking observed on certain day, tithi, month or other period of time for the attainment of desired fruits. Vrata is observed for worshipping deity, usually accompanied by restrictions to food and behaviour. Vrata is a definite resolve relating to a certain matter held as obligatory and may be positive like ‘I must do it' or negative ‘I must not do this’.

Concept of Vrata in the Purāṇas:

Though all the scriptures speak about vratas, it is the Purāṇas which give the utmost importance to the observance of vratas. Almost all the Purāṇas have discussed about the vratas and stressed the need for the perfomance of vratas and upavāsas. The authors of the Purāṇas have placed the vratas over the Vedic sacrifices.

The Brahmapurāṇa has stated that the observance of a vrata for the god Sūrya for one day only gives the reward which cannot be achieved by hundreds of Vedic sacrifices.[11] Thousands of vratas in the sense of self imposed, devout, or ceremonial observances of different sorts are described in the Purāṇas. The rules of the vratas in the Purāṇas have been very much liberalized to embrace different segments of people. For this reason the caste and gender restrictions have been reduced. Yet there had to be some rules guiding the whole process in order to protect and preserve the sanctity of the ritual system itself. According to the Agnipurāṇa, vrata involves certain regulations such as regular bath, limited food, worshipping god etc.[12] It also speaks of ten virtues which must be followed as common to all vratas, viz., forbearance, truthfulness, compassion, charity, purity of body and mind, curbing the organs of the senses, worship of deities, offering into fire, satisfaction and not depriving any other of his belonging.[13]

Upavāsa (fasting):

The central point of vrata is upavāsa i.e. fasting. The Viṣṇudharmottarapurāṇa, the Liṅgapurāṇa and the Matsyapurāṇa give a clear picture of the extent to which numerous vratas are performed with upavāsas. However, in the Matsyapurāṇa alternative rite is permitted for those who find it hard to observe a fast.[14] It is said in the Matsyapurāṇa that one who can not take a complete fast of 24 hours may take food after sunset and this is known as nākta.[15]

Saṅkalpa (mental resolve)

Purāṇas enjoin that before starting a vrata, saṅkalpa (mental resolve) is to be taken and there must be a pāraṇā in the conclusion of the vrata. In case of a fast or a vrata, saṅkalpa is to be generally made in the morning. Even when a tithi doesn’t begin in the morning the saṅkalpa has to be made in the morning. If no saṅkalpa is made, the devotee loses the merit of vrata and gets very little benefit from it.[16] For making a saṅkalpa one has to perform some rites to the gods.

The Garuḍapurāṇa has an ideal example of such saṅkalpa. It is found thus,

‘O God! I have undertaken this vrata in your presence; may it succeed without obstacles if you become favourable to me; after I undertake this vrata if I die when it is half finished, may it become completely fulfilled through your favour’.[17]

Udyāpana or Pāraṇā (concluding a fast)

On the other hand, a vrata comes to an end by a rite called udyāpana or pāraṇā. The Viṣṇudharmottarapurāṇa clearifies that a vrata ends with pāraṇā and at the end of a vrata, pāraṇa takes place the day after the day of the fast and is generally performed in the morning.[18] It is ordained that without doing pāraṇā of a vrata, another cannot be started. A vrata becomes fruitless if the udyāpana or pāranā is not performed.

The Padmapurāṇa classifies vratas into three categories, viz.,

- mental vratas,

- physical vratas and

- vratas of speech.

Non-violence, truthfulness, not depriving a person from his property by illegal means, continence and freedom from hypocracy are the mental vratas that lead to the satisfaction of Hari. Eating only once in the day, eating after the sunset (nakta), fasting, abstaining from begging etc are physical vratas for human beings. Study of the Vedas, recounting the name of Viṣṇu, speaking the truth and abstaining from backbiting are the vratas of speech.[19] Another classification is made on the basis of time i.e., for how much time a vrata lasts. A vrata may last for a day or a fortnight or a month, season, ayana, year etc. and on the basis of such time vratas are classified. Ayana is the time of the stay of the Sun in the northern or southern hemisphere.[20]

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Cf., M.M. Williams, Sankrit English Dictionary, p. 1042

[2]:

P.V.Kane, History of Dharmaśāstra, Vol.I, Part I, p. 5

[5]:

Cf. Atharvaveda, 20.25.5

[6]:

[7]:

Cf., vrate// Aṣṭādhyāyī, 3.2.80; mantre śvetavahokthaśaspuroḍāśoṇvin// Ibid., 3.2.71

[8]:

Cf., Mahābhārata, 3,296.3; 5,39.71-72

[9]:

vratamiti ca mānasam karmocyate/idaṃ na kariṣyāmīti yaḥ saṅkalpaḥ/ katamattad vratam // Śābarabhāṣya,VI. 2. 20

[10]:

brāhmaṇasyāvaśyakartavyāni vidhipratiṣedhātmakāni mānasasaṅkalparūpāṇis nātakavratānyāha/ Mitākṣarā on Yājñavalkyasmṛti, I.129

[11]:

ekāhenāpi yadbhānoḥ pūjāyāḥ prāpyate phalam/

yathoktadakṣiṇairviprairna tatkratuśatairapi//

–Brahmapurāṇa, 29.61

[12]:

[13]:

Ibid.,175.10-11

[14]:

upavāseṣvaśaktasya tadeva phalamicchataḥ/ anabhyāsena rogādvā kimiṣṭaṃ vratamuttamam// Matsyapurāṇa, 55.1

[16]:

Cf., P.V.Kane, History of Dharmaśāstra, Vol.V, Part I, p.82

[17]:

[18]:

Cf., P.V.Kane, History of Dharmaśāstra, Vol.V, Part.I, pp.120-121

[19]:

Padmapurāṇa, 4.84.42-44

[20]:

Cf., Visṇūpurāṇa, 2.8.65