Matangalila and Hastyayurveda (study)

by Chandrima Das | 2021 | 98,676 words

This page relates ‘Elephants in Shaivism’ of the study on the Matangalina and Hastyayurveda in the light of available epigraphic data on elephants in ancient India. Both the Matanga-Lila (by Nilakantha) and and the Hasti-Ayurveda (by Palakapya) represent technical Sanskrit works deal with the treatment of elephants. This thesis deals with their natural abode, capturing techniques, myths and metaphors, and other text related to elephants reflected from a historical and chronological cultural framework.

Elephants in Śaivism

In the countless battles between good and evil that enliven Brahmanical mythology, progress of all forms tries to destroy the universe to gain supremacy over the gods.

In this connection we can take a glance to a record the Chandrehe inscription of Prabodhasiva of Kalacuri year 724[1] this Śaiva grant gives a description of Śiva in which it is stated:

“May the mass of lustre of the laugh of Śaṅkara clad in an elephant-skin which white like the goose, in spread round his face and which, being slightly darkened by the effulgence of his (blue) neck, at once assumes the clear splendour of the moon emerging from a cloud-grant you prosperity!”

It also speaks that:

“Skilled in the cārī steps; which puts to flight the elephants of the quarters; which caused a sudden movement of a part of the universe by the revolutions of his staff-like arms and which is accompanied by the deep sound of the ḍamru.”[2]

This description reminds us about the Purāṇic story of Gajāsura–literally “elephant-demon”–varies little from a classic plot and asura takes the form of a monstrous elephant and goes out on the rampage. The gods in heaven watch helplessly and finally beg Śiva, the Destroyer, to bring an end to the menace. Śiva confronts elephant and challenged him in a dance to the death. Following a predictable climax, the god flags the hide off the demonic form and wraps it around himself. Draped in this macabre cloak and dripping with the monster’s blood, he proclaims his victory with a terrifying dance which may be mentioned here as cārī dance. Inscriptions like Tarpandighi grant of Lakṣmaṇasena[3] when describing Lord Sadāśiva who has ten arms; it speaks that in one of his right hands he holds an elephant goad considering our Puranic reference we can take this as a symbolic to the Gajāsura story where Śiva gets victory over an elephant demon. And thus the worshippers of Śiva invoke him by the name of Gajasaṃhāra.

[21. Gajāsura saṃhāra image and tāṇḍava nṛtya of Śiva within his belly, Hoysala temple, Belur]

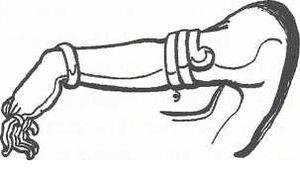

The darker side of Śiva’s dance emerges with his manifestation as Gajāsura-saṃhāramurti (Slayer of the Elephant-demon). A vivid cultural depiction at the Kāśiviśveśvara temple in Lakkundi shows Śiva clutching Gajāsura’s skin around himself with five of his ten hands. The elephant’s head lolls heavily to a side; its tail and one pair of stumpy legs have barely survived the elements. Weathering lends an added dimension to the imagery; like a leathery eggshell, the hide-cloak looks like it might crumble at the slightest hint of movement. Surrounding the grisly vignette is an unruly cluster of gods and goddesses, jostling; it would seem, for a better view. An equally animated rendering, at the Ghaṭeśvara temple Badoli in western India, shows a beard and grimacing Śiva with a garland of skulls slung around his neck. The elephant-skin cloak is almost incidental in composition. Similar version can also be seen in the courtyard of the Virūpākṣa temple in Pattadakal. Śiva here sticks a stiffly exultant pose; his smile is inscrutable. Gajāsura’s hide forms a taut back drop that also defines the frame. Śiva suppressed the elephant’s head with his left foot. His ancillary right arm assumes the Gaja-hasta (elephant-hand) posture. The fingers pointing to the right foot are symbolic of leading the devout on the faith to salvation.[4] In some of the legends it is said that the head of this Gajāsura was used on Gaṇeśa’s head.

[22. Gaja-hasta mudrā]

The hand of Śiva plays a significant role in the creation of Gaṇeśa–much-loved elephantheaded god of wisdom and patron of literary and academic persuades. The mythology of the rubicund deity is varied and complex. In the most popular tale of Gaṇeśa’s creation, Śiva’s consort Pārvatī fashions a boy-child out of rubbings from her own body and instructs him to guard the house while she goes in for a bath. Śiva returns home to find a stranger minding the front door. Because the obedient denies him entry, Śiva lops the youngster’s head off. Pārvatī emerges from her bath and is distraught. To mollify his wife, Śiva replaces the child’s head with that of the first animal he comes across–which happens to be an elephant–and restores life into the little boy. Also known as Gaṇapati (Lord of the Gaṇas), Vigneśvara (remover of obstacles) and Eka-danta (one tusked), Gaṇeśa the elephant headed God is invoked in the beginning of any new work or assignment for an auspicious commencement. His iconography, therefore, is hugely eclectic. An especially charming depiction, in a cavetemple at Udayagiri, Central India, shows the god seated like a quiet and introspective child.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

EI, Vol. XXI, pp. 149-151.

[2]:

CII, Vol. IV, pp. 198-204.

[3]:

EI, Vol. XII, pp. 6-7.

[4]:

V. Ram., pp. 37-38.