Brahma Sutras (Ramanuja)

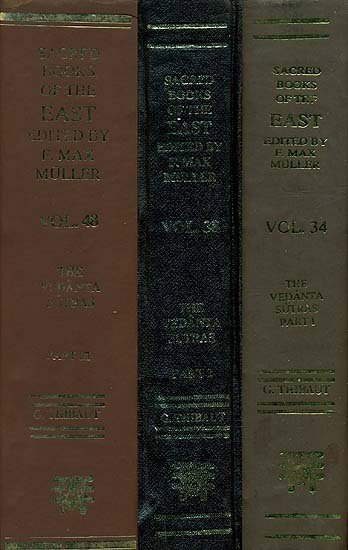

by George Thibaut | 1904 | 275,953 words | ISBN-10: 8120801350 | ISBN-13: 9788120801356

The English translation of the Brahma Sutras (also, Vedanta Sutras) with commentary by Ramanuja (known as the Sri Bhasya). The Brahmasutra expounds the essential philosophy of the Upanishads which, primarily revolving around the knowledge of Brahman and Atman, represents the foundation of Vedanta. Ramanjua’s interpretation of these sutras from a V...

Sutra 1.4.11

11. Not from the mention of the number even, on account of the diversity and of the excess.

The Vājasaneyins read in their text 'He in whom the five "five-people" and the ether rest, him alone I believe to be the Self; I, who know, believe him to be Brahman' (Bṛ. Up. IV, 4, 17). The doubt here arises whether this text be meant to set forth the categories as established in Kapila’s doctrine, or not.—The Pūrvapakshin maintains the former view, on the ground that the word 'five-people,' qualified by the word 'five,' intimates the twenty-five categories of the Sāṅkhyas. The compound 'five-people' (pañcajanāḥ) denotes groups of five beings, just as the term pañca-pūlyaḥ denotes aggregates of five bundles of grass. And as we want to know how many such groups there are, the additional qualification 'five' intimates that there are five such groups; just as if it were said 'five five-bundles, i. e. five aggregates consisting of five bundles each.' We thus understand that the 'five five-people' are twenty-five things, and as the mantra in which the term is met with refers to final release, we recognise the twenty-five categories known from the Sāṅkhya-smṛti which are here referred to as objects to be known by persons desirous of release. For the followers of Kapila teach that 'there is the fundamental causal substance which is not an effect. There are seven things, viz. the Mahat, and so on, which are causal substances as well as effects. There are sixteen effects. The soul is neither a causal substance nor an effect' (Sāṅ. Kā. 3). The mantra therefore is meant to intimate the categories known from the Sāṅkhya.—To this the Sūtra replies that from the mention of the number twenty-five supposed to be implied in the expression 'the five five-people,' it does not follow that the categories of the Sāṅkhyas are meant. 'On account of the diversity,' i.e. on account of the five-people further qualified by the number five being different from the categories of the Sāṅkhyas. For in the text 'in whom the five five-people and the ether rest,' the 'in whom' shows the five-people to have their abode, and hence their Self, in Brahman; and in the continuation of the text, 'him I believe the Self,' the 'him' connecting itself with the preceding 'in whom' is recognised to be Brahman. The five five-people must therefore be different from the categories of the Sāṅkhya-system. 'And on account of the excess.' Moreover there is, in the text under discussion, an excess over and above the Sāṅkhya categories, consisting in the Self denoted by the relative pronoun 'in whom,' and in the specially mentioned Ether. What the text designates therefore is the Supreme Person who is the Universal Lord in whom all things abide—such as he is described in the text quoted above, 'Therefore some call him the twenty-sixth, and others the twenty-seventh.' The 'even' in the Sūtra is meant to intimate that the 'five five-people' can in no way mean the twenty-five categories, since there is no pentad of groups consisting of five each. For in the case of the categories of the Sāṅkhyas there are no generic characteristics or the like which could determine the arrangement of those categories in fives. Nor must it be urged against this that there is a determining reason for such an arrangement in so far as the tattvas of the Sāṅkhyas form natural groups comprising firstly, the five organs of action; secondly, the five sense-organs; thirdly, the five gross elements; fourthly, the subtle parts of those elements; and fifthly, the five remaining tattvas; for as the text under discussion mentions the ether by itself, the possibility of a group consisting of the five gross elements is precluded. We cannot therefore take the compound 'five people' as denoting a group consisting of five constituent members, but, in agreement with Pāṇ. II, 1, 50, as merely being a special name. There are certain beings the special name of which is 'five-people,' and of these beings the additional word 'pañca' predicates that they are five in number. The expression is thus analogous to the term 'the seven seven-ṛshis'(where the term 'seven-ṛshis' is to be understood as the name of a certain class of ṛshis only).—Who then are the beings called 'five-people?'—To this question the next Sūtra replies.