Brahma Sutras (Ramanuja)

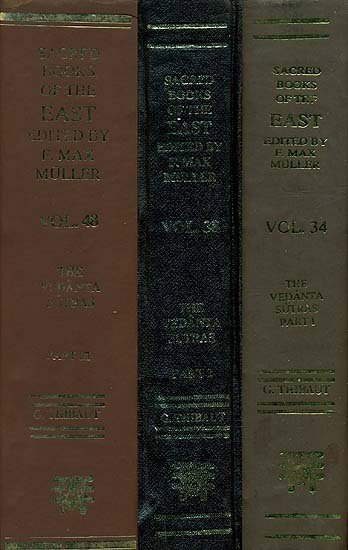

by George Thibaut | 1904 | 275,953 words | ISBN-10: 8120801350 | ISBN-13: 9788120801356

The English translation of the Brahma Sutras (also, Vedanta Sutras) with commentary by Ramanuja (known as the Sri Bhasya). The Brahmasutra expounds the essential philosophy of the Upanishads which, primarily revolving around the knowledge of Brahman and Atman, represents the foundation of Vedanta. Ramanjua’s interpretation of these sutras from a V...

Sutra 1.4.1

1. If it be said that some (mention) that which rests on Inference; we deny this because (the form) refers to what is contained in the simile of the body; and (this the text) shows.

So far the Sūtras have given instruction about a Brahman, the enquiry into which serves as a means to obtain what is the highest good of man, viz. final release; which is the cause of the origination, and so on, of the world; which differs in nature from all non-sentient things such as the Pradhāna, and from all intelligent beings whether in the state of bondage or of release; which is free from all shadow of imperfection; which is all knowing, all powerful, has the power of realising all its purposes, comprises within itself all blessed qualities, is the inner Self of all, and possesses unbounded power and might. But here a new special objection presents itself. In order to establish the theory maintained by Kapila, viz. of there being a Pradhāna and individual souls which do not have their Self in Brahman, it is pointed out by some that in certain branches of the Veda there are met with certain passages which appear to adumbrate the doctrine of the Pradhāna being the universal cause. The Sūtras now apply themselves to the refutation of this view, in order thereby to confirm the theory of Brahman being the only cause of all.

We read in the Kaṭha-Upanishad, 'Beyond the senses there are the objects, beyond the objects there is the mind, beyond the mind there is the intellect, the great Self is beyond the intellect. Beyond the Great there is the Unevolved, beyond the Unevolved there is the Person. Beyond the Person there is nothing—this is the goal, the highest road' (Ka. Up. I, 3, 11). The question here arises whether by the 'Unevolved' be or be not meant the Pradhāna, as established by Kapila’s theory, of which Brahman is not the Self.—The Pūrvapakshin maintains the former alternative. For, he says, in the clause 'beyond the Great is the Unevolved, beyond the Unevolved is the Person,' we recognise the arrangement of entities as established by the Sāṅkhya-system, and hence must take the 'Unevolved' to be the Pradhāna. This is further confirmed by the additional clause 'beyond the Person there is nothing,' which (in agreement with Sāṅkhya principles) denies that there is any being beyond the soul, which itself is the twenty-fifth and last of the principles recognised by the Sāṅkhyas. This primā facie view is expressed in the former part of the Sūtra, 'If it be said that in the śākhās of some that which rests on Inference, i.e. the Pradhāna, is stated as the universal cause.'

The latter part of the Sūtra refutes this view. The word 'Unevolved' does not denote a Pradhāna independent of Brahman; it rather denotes the body represented as a chariot in the simile of the body, i.e. in the passage instituting a comparison between the Self, body, intellect, and so on, on the one side, and the charioteer, chariot, etc. on the other side.—The details are as follows. The text at first—in the section beginning 'Know the Self to be the person driving,' etc., and ending 'he reaches the end of the journey, and that is the highest place of Vishṇu' (I, 3, 3-9)—compares the devotee desirous of reaching the goal of his journey through the saṃsāra, i.e. the abode of Vishṇu, to a man driving in a chariot; and his body, senses, and so on, to the chariot and parts of the chariot; the meaning of the whole comparison being that he only reaches the goal who has the chariot, etc. in his control. It thereupon proceeds to declare which of the different beings enumerated and compared to a chariot, and so on, occupy a superior position to the others in so far, namely, as they are that which requires to be controlled—'higher than the senses are the objects,' and so on. Higher than the senses compared to the horses—are the objects—compared to roads,—because even a man who generally controls his senses finds it difficult to master them when they are in contact with their objects; higher than the objects is the mind-compared to the reins—because when the mind inclines towards the objects even the non-proximity of the latter does not make much difference; higher than the mind (manas) is the intellect (buddhi)—compared to the charioteer—because in the absence of decision (which is the characteristic quality of buddhi) the mind also has little power; higher than the intellect again is the (individual) Self, for that Self is the agent whom the intellect serves. And as all this is subject to the wishes of the Self, the text characterises it as the 'great Self.' Superior to that Self again is the body, compared to the chariot, for all activity whereby the individual Self strives to bring about what is of advantage to itself depends on the body. And higher finally than the body is the highest Person, the inner Ruler and Self of all, the term and goal of the journey of the individual soul; for the activities of all the beings enumerated depend on the wishes of that highest Self. As the universal inner Ruler that Self brings about the meditation of the Devotee also; for the Sūtra (II, 3, 41) expressly declares that the activity of the individual soul depends on the Supreme Person. Being the means for bringing about the meditation and the goal of meditation, that same Self is the highest object to be attained; hence the text says 'Higher than the Person there is nothing—that is the goal, the highest road.' Analogously scripture, in the antaryāmin-Brāhmaṇa, at first declares that the highest Self within witnesses and rules everything, and thereupon negatives the existence of any further ruling principle 'There is no other seer but he,' etc. Similarly, in the Bhagavad-gītā, 'The abode, the agent, the various senses, the different and manifold functions, and fifth the Divinity (i.e. the highest Person)' (XVIII, 14); and 'I dwell within the heart of all; memory and perception, as well as their loss, come from me' (XV, 15). And if, as in the explanation of the text under discussion, we speak of that highest Self being 'controlled,' we must understand thereby the soul’s taking refuge with it; compare the passage Bha. Gī. XVIII, 61-62, 'The Lord dwells in the heart of all creatures, whirling them round as if mounted on a machine; to Him go for refuge.'

Now all the beings, senses, and so on, which had been mentioned in the simile, are recognised in the passage 'higher than the senses are the objects,' etc., being designated there by their proper names; but there is no mention made of the body which previously had been compared to the chariot; we therefore conclude that it is the body which is denoted by the term 'the Unevolved.' Hence there is no reason to see here a reference to the Pradhāna as established in the theory of Kapila. Nor do we recognise, in the text under discussion, the general system of Kapila. The text declares the objects, i.e. sounds and so on, to be superior to the senses; but in Kapila’s system the objects are not viewed as the causes of the senses. For the same reason the statement that the manas is higher than the objects does not agree with Kapila’s doctrine. Nor is this the case with regard to the clause 'higher than the buddhi is the great one, the Self; for with Kapila the 'great one' (mahat) is the buddhi, and it would not do to say 'higher than the great one is the great one.' And finally the 'great one,' according to Kapila, cannot be called the 'Self.' The text under discussion thus refers only to those entities which had previously appeared in the simile. The text itself further on proves this, when saying 'That Self is hidden in all beings and does not shine forth, but it is seen by subtle seers through their sharp and subtle intellect. A wise man should keep down speech in the mind, he should keep that within knowledge (which is) within the Self; he should keep knowledge within the great Self, and that he should keep within the quiet Self.' For this passage, after having stated that the highest Self is difficult to see with the inner and outer organs of knowledge, describes the mode in which the sense-organs, and so on, are to be held in control. The wise man should restrain the sense-organs and the organs of activity within the mind; he should restrain that (i.e. the mind) within knowledge, i.e. within the intellect (buddhi), which abides within the Self; he should further restrain the intellect within the great Self, i.e. the active individual Self; and that Self finally he should restrain within the quiet Self, i.e. the highest Brahman, which is the inner ruler of all; i.e. he should reach, with his individual Self so qualified, the place of Vishṇu, i.e. Brahman.—But how can the term 'the Unevolved' denote the evolved body?—To this question the next Sūtra furnishes a reply.