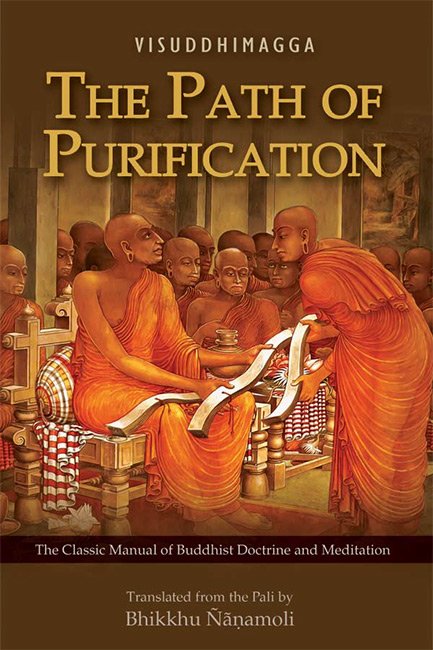

Visuddhimagga (the pah of purification)

by Ñāṇamoli Bhikkhu | 1956 | 388,207 words | ISBN-10: 9552400236 | ISBN-13: 9789552400236

The English translation of the Visuddhimagga written by Buddhaghosa in the 5th Century. It contains the essence of the the teachings found in the Pali Tripitaka and represents, as a whole, an exhaustive meditation manual. The work consists of the three parts—1) Virtue (Sila), 2) Concentration (Samadhi) and 3) Understanding (Panna) covering twenty-t...

Concerning the Translation

The pitfalls that await anyone translating from another European language into his own native English are familiar enough; there is no need for him to fall into them. But when he ventures upon rendering an Oriental language, he will often have to be his own guide.

Naturally, a translator from Pali today owes a large debt to his predecessors and to the Pali Text Society’s publications, including in particular the Society’s invaluable Pali-English Dictionary. A translator of the Visuddhimagga, too, must make due acknowledgement of its pioneer translation[1] U Pe Maung Tin.

The word pāḷi is translatable by “text.” The pāḷi language (the “text language,” which the commentators call Magadhan) holds a special position, with no European parallel, being reserved to one field, namely, the Buddha’s teaching. So there are no alien echoes. In the Suttas, the Sanskrit is silent, and it is heavily muted in the later literature. This fact, coupled with the richness and integrity of the subject itself, gives it a singular limpidness and depth in its early form, as in a string quartet or the clear ocean, which attains in the style of the Suttas to an exquisite and unrivalled beauty unreflectable by any rendering. Traces seem to linger even in the intricate formalism preferred by the commentators.

This translation presents many formidable problems. Mainly either epistemological and psychological, or else linguistic, they relate either to what ideas and things are being discussed, or else to the manipulation of dictionary meanings of words used in discussion.

The first is perhaps dominant. As mentioned earlier, the Visuddhimagga can be properly studied only as part of the whole commentarial edifice, whose cornerstone it is. But while indexes of words and subjects to the PTS edition of the Visuddhimagga exist, most of its author’s works have only indexes of Piṭaka words and names commented on but none for the mass of subject matter. So the student has to make his own. Of the commentaries too, only the Atthasālinī, the Dhammapada Commentary, and the Jātaka Commentary have so far been translated (and the latter two are rather in a separate class). But that is a minor aspect.

This book is largely technical and presents all the difficulties peculiar to technical translation: it deals, besides, with mental happenings. Now where many synonyms are used, as they often are in Pali, for public material objects—an elephant, say, or gold or the sun—the “material objects” should be pointable to, if there is doubt about what is referred to. Again even such generally recognized private experiences as those referred to by the words “consciousness” or “pain” seem too obvious to introspection for uncertainty to arise (communication to fail) if they are given variant symbols. Here the English translator can forsake the Pali allotment of synonyms and indulge a liking for “elegant variation,” if he has it, without fear of muddle. But mind is fluid, as it were, and materially negative, and its analysis needs a different and a strict treatment. In the Suttas, and still more in the Abhidhamma, charting by analysis and definition of pin-pointed mental states is carried far into unfamiliar waters. It was already recognized then that this is no more a solid landscape of “things” to be pointed to when variation has resulted in vagueness. As an instance of disregard of this fact: a greater scholar with impeccable historical and philological judgment (perhaps the most eminent of the English translators) has in a single work rendered the cattāro satipaṭṭhāna (here represented by “four foundations of mindfulness”) by “four inceptions of deliberation,” “fourfold setting up of mindfulness,” “fourfold setting up of starting,” “four applications of mindfulness,” and other variants. The PED foreword observes: “No one needs now to use the one English word ‘desire’ as a translation of sixteen distinct Pali words, no one of which means precisely desire. Yet this was done in Vol. X of the Sacred Books of the East by Max Müller and Fausböll.” True; but need one go to the other extreme? How without looking up the Pali can one be sure if the same idea is referred to by all these variants and not some other such as those referred to by cattāro iddhipādā (“four roads to power” or “bases of success”), cattāro sammappadhānā (“four right endeavours”), etc., or one of the many other “fours”? It is customary not to vary, say, the “call for the categorical imperative” in a new context by some such alternative as “uncompromising order” or “plain-speaking bidding” or “call for unconditional surrender,” which the dictionaries would justify, or “faith” which the exegetists might recommend; that is to say, if it is hoped to avoid confusion. The choosing of an adequate rendering is, however, a quite different problem.

But there is something more to be considered before coming to that. So far only the difficulty of isolating, symbolizing, and describing individual mental states has been touched on. But here the whole mental structure with its temporaldynamic process is dealt with too. Identified mental as well as material states (none of which can arise independently) must be recognizable with their associations when encountered in new circumstances: for here arises the central question of thought-association and its manipulation. That is tacitly recognized in the Pali. If disregarded in the English rendering the tenuous structure with its inferences and negations—the flexible pattern of thought-associations—can no longer be communicated or followed, because the pattern of speech no longer reflects it, and whatever may be communicated is only fragmentary and perhaps deceptive. Renderings of words have to be distinguished, too, from renderings of words used to explain those words. From this aspect the Oriental system of word-by-word translation, which transliterates the sound of the principal substantive and verb stems and attaches to them local inflections, has much to recommend it, though, of course, it is not readable as “literature.” One is handling instead of pictures of isolated ideas or even groups of ideas a whole coherent chart system. And besides, words, like maps and charts, are conventionally used to represent high dimensions.

When already identified states or currents are encountered from new angles, the new situation can be verbalized in one of two ways at least: either by using in a new appropriate verbal setting the words already allotted to these states, or by describing the whole situation afresh in different terminology chosen ad hoc. While the second may gain in individual brightness, connections with other allied references can hardly fail to be lost. Aerial photographs must be taken from consistent altitudes, if they are to be used for making maps. And words serve the double purpose of recording ideas already formed and of arousing new ones.

Structural coherence between different parts in the Pali of the present work needs reflecting in the translation—especially in the last ten chapters—if the thread is not soon to be lost. In fact, in the Pali (just as much in the Tipiṭaka as in its Commentaries), when such subjects are being handled, one finds that a tacit rule, “One term and one flexible definition for one idea (or state or event or situation) referred to,” is adhered to pretty thoroughly. The reason has already been made clear. With no such rule, ideas are apt to disintegrate or coalesce or fictitiously multiply (and, of course, any serious attempt at indexing in English is stultified). One thing needs to be made clear, though; for there is confusion of thought on this whole subject (one so far only partly investigated).[2]This “rule of parsimony in variants” has nothing to do with mechanical transliteration, which is a translator’s refuge when he is unsure of himself. The guiding rule, “One recognizable idea, one word, or phrase to symbolize it,” in no sense implies any such rule as, “One Pali word, one English word,” which is neither desirable nor practicable. Nor in translating need the rule apply beyond the scope reviewed.

So much for the epistemological and psychological problems.

The linguistic problem is scarcely less formidable though much better recognized. While English is extremely analytic, Pali (another Indo-European language) is one of the groups of tongues regarded as dominated by Sanskrit, strongly agglutinative, forming long compounds and heavily inflected. The vocabulary chosen occasioned much heart-searching but is still very imperfect. If a few of the words encountered seem a bit algebraical at first, contexts and definitions should make them clear. In the translation of an Oriental language, especially a classical one, the translator must recognize that such knowledge which the Oriental reader is taken for granted to possess is lacking in his European counterpart, who tends unawares to fill the gaps from his own foreign store: the result can be like taking two pictures on one film. Not only is the common background evoked by the words shadowy and patchy, but European thought and Indian thought tend to approach the problems of human existence from opposite directions. This affects word formations. And so double meanings (utraquisms, puns, and metaphors) and etymological links often follow quite different tracks, a fact which is particularly intrusive in describing mental events, where the terms employed are mainly “material” ones used metaphorically. Unwanted contexts constantly creep in and wanted ones stay out. Then there are no well-defined techniques for recognizing and handling idioms, literal rendering of which misleads (while, say, one may not wonder whether to render tour de force by “enforced tour” or “tower of strength,” one cannot always be so confident in Pali).

Then again in the Visuddhimagga alone the actual words and word-meanings not in the PED come to more than two hundred and forty. The PED, as its preface states, is “essentially preliminary”; for when it was published many books had still not been collated; it leaves out many words even from the Sutta Piṭaka, and the Sub-commentaries are not touched by it. Also—and most important here—in the making of that dictionary the study of Pali literature had for the most part not been tackled much from, shall one say, the philosophical, or better, epistemological, angle,[3] work and interest having been concentrated till then almost exclusively on history and philology. For instance, the epistemologically unimportant word vimāna (divine mansion) is given more than twice the space allotted to the term paṭiccasamuppāda (dependent origination), a difficult subject of central importance, the article on which is altogether inadequate and misleading (owing partly to misapplication of the “historical method”). Then gala (throat) has been found more glossarialy interesting than paṭisandhi (rebirth-linking), the original use of which word at M III 230 is ignored. Under nāma, too, nāma-rūpa is confused with nāmakāya. And so one might continue. By this, however, it is not intended at all to depreciate that great dictionary, but only to observe that in using it the Pali student has sometimes to be wary: if it is criticized in particular here (and it can well hold its own against criticism), tribute must also be paid to its own inestimable general value.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Reprinted by the Pali Text Society as Path of Purity, 1922–31.

[2]:

See Prof. I. A. Richards, Mencius on Mind, Kegan Paul, 1932.

[3]:

Exceptions are certain early works of Mrs. C.A.F. Rhys Davids. See also discussions in appendixes to the translations of the Kathāvatthu (Points of Controversy, PTS) and the Abhidhammatthasaṅgaha (Compendium of Philosophy, PTS). lii