Dhammapada (Illustrated)

by Ven. Weagoda Sarada Maha Thero | 1993 | 341,201 words | ISBN-10: 9810049382 | ISBN-13: 9789810049386

This page describes The Story of the Pacification of the Relatives of the Buddha which is verse 197-199 of the English translation of the Dhammapada which forms a part of the Sutta Pitaka of the Buddhist canon of literature. Presenting the fundamental basics of the Buddhist way of life, the Dhammapada is a collection of 423 stanzas. This verse 197-199 is part of the Sukha Vagga (Happiness) and the moral of the story is “For those who harbour no enmity it is blissful to live even among enemies” (first part only).

Verse 197-199 - The Story of the Pacification of the Relatives of the Buddha

Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 197-199:

susukhaṃ vata jīvāma verinesu averino |

verinesu manussesu viharāma averino || 197 ||

susukhaṃ vata jīvāma āturesu anāturā |

āturesu manussesu viharāma anāturā || 198 ||

susukhaṃ vata jīvāma ussūkesu anussukā |

ussukesu manussesu viharāma anussukā || 199 ||

197. We the unhating live happily midst the haters, among the hating humans from hatred dwell we free.

198. We who are healthy live happily midst the unhealthy, among unhealthy humans from ill-health dwell we free.

199. We the unfrenzied live happily midst the frenzied, among the frenzied humans from frenzy dwell we free.

For those who harbour no enmity it is blissful to live even among enemies. |

It is comfort indeed to live among the diseased for those with feelings of good health. |

Unagitated we live in comfort in the midst of highly agitated worldlings. |

The Story of the Pacification of the Relatives of the Buddha

The Buddha spoke these verses in the country of Sākyan with reference to the relatives who were quarrelling over the use of the waters of the Rohinī River.

The story goes that the Sākyas and the Koliyas caused the water of the River Rohinī to be confined by a single dam between the city of Kapilavatthu and the city of Koliya, and cultivated the fields on both sides of the river. Now in the month Jeṭṭhamūla the crops began to fail, whereupon the labourers employed by the residents of both cities assembled. Said the residents of the city of Koliya, “If this water is diverted to both sides of the river, there will not be enough both for you and for us too. But our crops will ripen with a single watering. Therefore let us have the water.”

The Sākyas replied, “After you have filled your storehouses, we shall not have the heart to take gold and emeralds and pennies, and, baskets and sacks in our hands, go from house to house seeking favours at your hands. Our crops also will ripen with a single watering. Therefore let us have this water.” ‘We will not give it to you.” “Neither will we give it to you.” The talk waxed bitterly until finally one arose and struck another a blow. The other returned the blow and a general fight ensued, the combatants making matters worse by casting aspersions on the origin of the two royal families.

Said the labourers employed by the Koliyas, “You who live in the city of Kapilavatthu, take your children and go where you belong. Are we likely to suffer harm from the elephants and horses and shields and weapons of those who, like dogs and jackals, have cohabited with their own sisters?” The labourers employed by the Sākyas replied, “You lepers, take your children and go where you belong. Are we likely to suffer harm from the elephants and horses and shields and weapons of destitute outcasts who have lived in the trees like animals?” Both parties of labourers went and reported the quarrel to the ministers who had charge of the work, and the ministers reported the matter to the royal households. Thereupon the Sākyas came forth armed for battle and cried out, “We will show what strength and power belong to those who have cohabited with their sisters.” Likewise the Koliyas came forth armed for battle and cried out, ‘We will show what strength and power belong to those who dwell in the trees.”

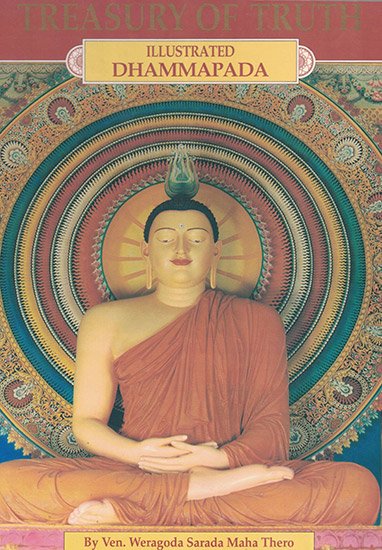

As the Buddha surveyed the world at dawn and beheld his kinsmen, he thought to himself, “If I refrain from going to them, these men will destroy each other. It is clearly my duty to go to them.” Accordingly he flew through the air quite alone to the spot where his kinsmen were gathered together, and seated himself cross-legged in the air over the middle of the Rohinī River. When the Buddha’s kinsmen saw the Buddha, they threw away their weapons and did reverence to Him. Said the Buddha to His kinsmen, “What is all this quarrel about, great king?” ‘We do not know, Venerable.” “Who then would be likely to know?” “The commander-in-chief of the army would be likely to know.” The commander-in-chief of the army said, “The viceroy would be likely to know.” Thus the Buddha put the question first to one and then to another, asking the slavelabourers last of all. The slave-labourers replied, “The quarrel is about water.”

Then the Buddha asked the king, “How much is water worth, great king?” “Very little, Venerable.” “How much are Sākyas worth, great king?” “Sākyas are beyond price, Venerable.” “It is not fitting that because of a little water you should destroy Sākyas who are beyond price.” They were silent. Then the Buddha addressed them and said, “Great kings, why do you act in this manner? Were I not here present today, you would set flowing a river of blood. You have acted in a most unbecoming manner. You live in enmity, indulging in the five kinds of hatred. I live free from hatred. You live afflicted with the sickness of the evil passions. I live free from disease. I live free from the eager pursuit of anything.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 197)

verinesu averino vata susukhaṃ jīvāma

manussesu verinesu averino viharāma

verinesu: among those filled with hatred; averino vata: indeed without hatred; susukhaṃ [susukha]: happily; jīvāma: we dwell; manussesu: among people; verinesu: who are full of hatred; averino [averina]: without hatred; viharāma: (we) continue to live

Among those who hate, we live without hating. When they hate we live without hating. We live extremely happily among those who hate.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 198)

āturesu anāturā vata susukhaṃ jīvāma

manussesu āturesu anāturā viharāma

āturesu: among those who are sick (with defilements); anāturā: (we) free of sickness; vata: indeed; susukhaṃ [susukha]: in extreme happiness; jīvāma: we live; manussesu āturesu: among those people who are sick; anāturā: without being sick; viharāma: we live

Among those who are sick, afflicted by defilements, we, who are not so afflicted, live happily. Among the sick we live, unafflicted, in extreme happiness.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 199)

ussukesu anussukā vata susukhaṃ jīvāma

manussesu ussukesu anussukā viharāma

ussukesu: among those who anxiously pursue worldly pleasures; anussukā: without such an effort; vata susukhaṃ [susukha]: indeed extremely happily; jīvāma: we dwell; manussesu: among those men; ussukesu: who make an anxious effort; anussukā: without making such an effort; viharāma: (we) continue to live

Among those anxious men and women, who ceaselessly exert themselves in the pursuit of worldly things. We, who do not make such a feverish effort to pursue the worldly, live extremely happily. Among those who seek the worldly, among men who seek pleasure, we live without seeking pleasures.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 197-199)

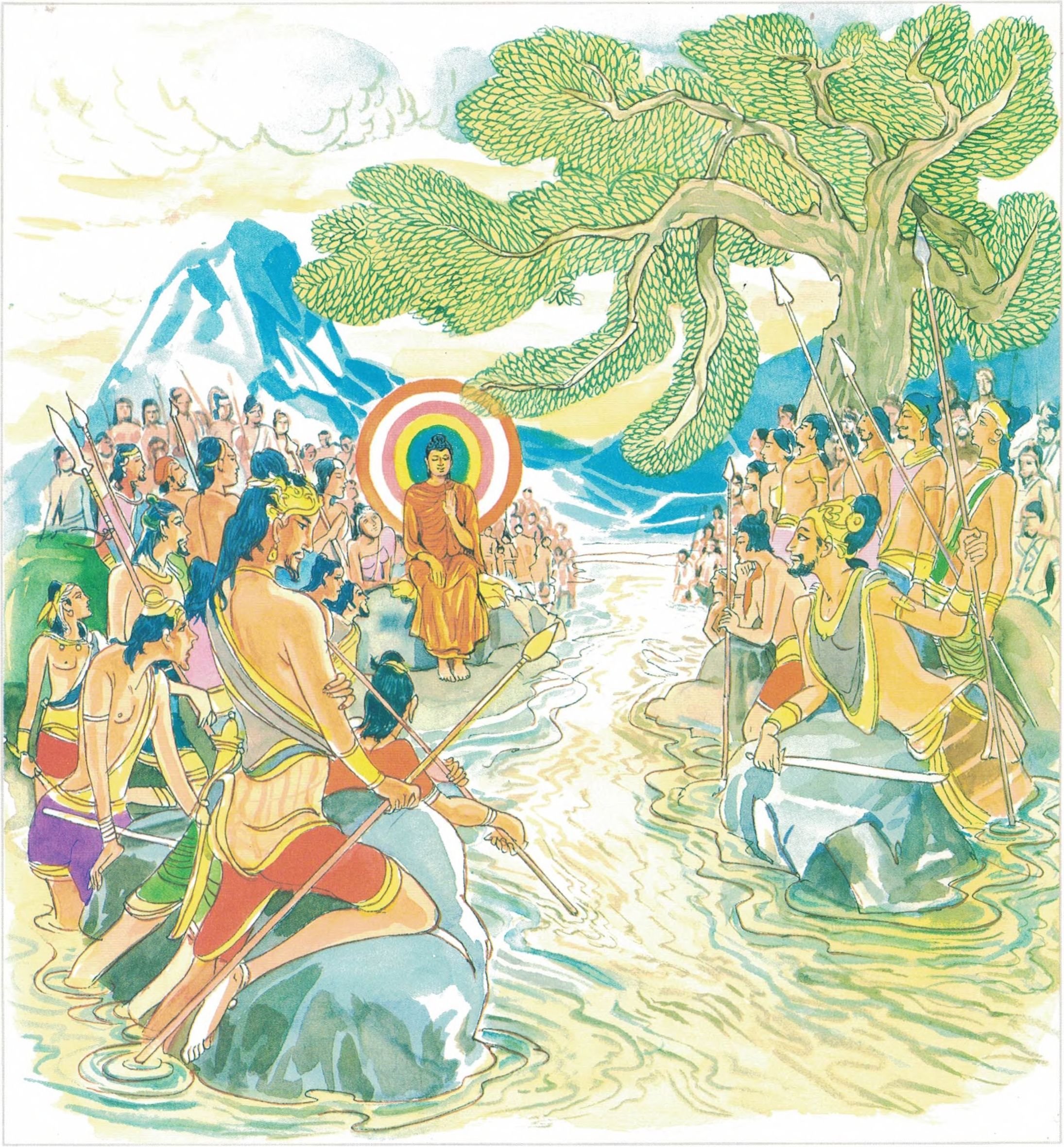

These verses were spoken by the Buddha, when he averted a conflict that would have escalated into a bloody war between clans who were His relations. The Buddha was born Prince Siddhattha, the son of King Suddhodana, a Sākya ruler. The Buddha’s (Prince Siddhattha’s) intimate relatives were closely linked with the Buddhist Sangha. Prince Siddhattha’s mother, Queen Mahāmāyā died within a few days of the Prince’s birth. Yasoddharā, Prince Siddhattha’s wife, was a cousin of his. Princess Yasoddharā, also known as Rāhulamātā, Bimbā and Bhaddakaccānā, was the daughter of King Suppabuddha, who reigned over the Koliya race, and Pamitā, sister of King Suddhodana. She was of the same age as Prince Siddhattha, whom she married at the age of sixteen. It was by exhibiting his military strength that he won her hand. She led an extremely happy and luxurious life. In her twenty-ninth year, on the very day she gave birth to her only son, Rāhula, her wise and contemplative husband, whom she loved with all her heart, resolved to renounce the world to seek deliverance from the ills of life. Without even bidding farewell to his faithful and charming wife, he left the palace at night, leaving young Yasoddharā to look after the child by herself. She awoke as usual to greet her beloved husband, but, to her surprise, she found him missing. When she realized that her ideal prince had left her and the new-born baby, she was overcome with indescribable grief. Her dearest possession was lost forever. The palace with all its allurements was now a dungeon; the whole world appeared to be blank. Her only consolation was her infant son. Though several Kshatriya princes sought her hand, she rejected all those proposals, and lived ever faithful to her beloved husband. Hearing that her husband was leading a hermit’s life, she removed all her jewellery and wore plain yellow garb. Throughout the six years during which the ascetic Gotama struggled for enlightenment Princess Yasoddharā watched His actions closely and did likewise. When the Buddha visited Kapilavatthu after His Enlightenment and was being entertained by the king in the palace on the following day all but the Princess Yasoddharā came to pay their reverence to Him. She thought, “Certainly if there is any virtue in me, the Buddha will come to my presence. Then will I reverence Him.”

After the meal was over the Buddha handed over the bowl to the king, and, accompanied by His two chief disciples, entered the chamber of Yasoddharā, and sat on a seat prepared for Him, saying, “Let the king’s daughter reverence me as she likes. Say nothing.” Hearing of the Buddha’s visit, she bade the ladies in the court wear yellow garments. When the Buddha took His seat, Yasoddharā came swiftly to Him and clasping His ankles, placed her head on His feet and reverenced Him as she liked. Demonstrating her affection and respect thus, she sat down with due reverence. Then the king praised her virtues and, commenting on her love and loyalty, said, “Lord, when my daughter heard that you were wearing yellow robes, she also robed herself in yellow; when she heard that you were taking one meal a day, she also did the same; when she heard that you had given up lofty couches, she lay on a low couch; when she heard that you had given up garlands and scents, she also gave them up; when her relatives sent messages to say that they would maintain her, she did not even look at a single one. So virtuous was my daughter.”

“Not only in this last birth, O’ king, but in a previous birth, too, she protected me and was devoted and faithful to me,” remarked the Buddha and cited the Candakinnara Jātaka. Recalling this past association with her, He consoled her and left the palace. After the death of King Suddhodana, when Pajāpatī Gotamī became a nun (bhikkhunī), Yasoddharā also entered the Sangha and attained arahatship.

Amongst women disciples she was the chief of those who attained great supernormal powers (mahā abhiññā). At the age of seventy-eight she passed away. Her name does not appear in the Therīgāthā but her interesting verses are found in the Apādana.

Rāhula was the only son of Prince Siddhattha and Princess Yasoddharā. He was born on the day when Prince Siddhattha decided to renounce the world. The happy news of the birth of his infant son was conveyed to him when he was in the park in a contemplative mood. Contrary to ordinary expectations, instead of rejoicing over the news, he exclaimed, “Rahu jāto, bandhanam jātam” (Rahu is born, a fetter has arisen!) Accordingly, the child was named Rāhula by King Suddhodana, his grandfather.

Rāhula was brought up as a fatherless child by his mother and grandfather. When he was seven years old, the Buddha visited Kapilavatthu for the first time after His Enlightenment. On the seventh day after His arrival Princess Yasoddharā gaily dressed up young Rāhula and pointing to the Buddha, said, “Behold, son, that ascetic, looking like Brahma, surrounded by twenty thousand ascetics! He is your father, and He had great treasures. Since His renunciation we do not see them. Go up to him and ask for your inheritance, and say, “Father, I am the prince. After my consecration I will be a universal monarch. I am in need of wealth. Please give me wealth, for the son is the owner of what belongs to the father.”

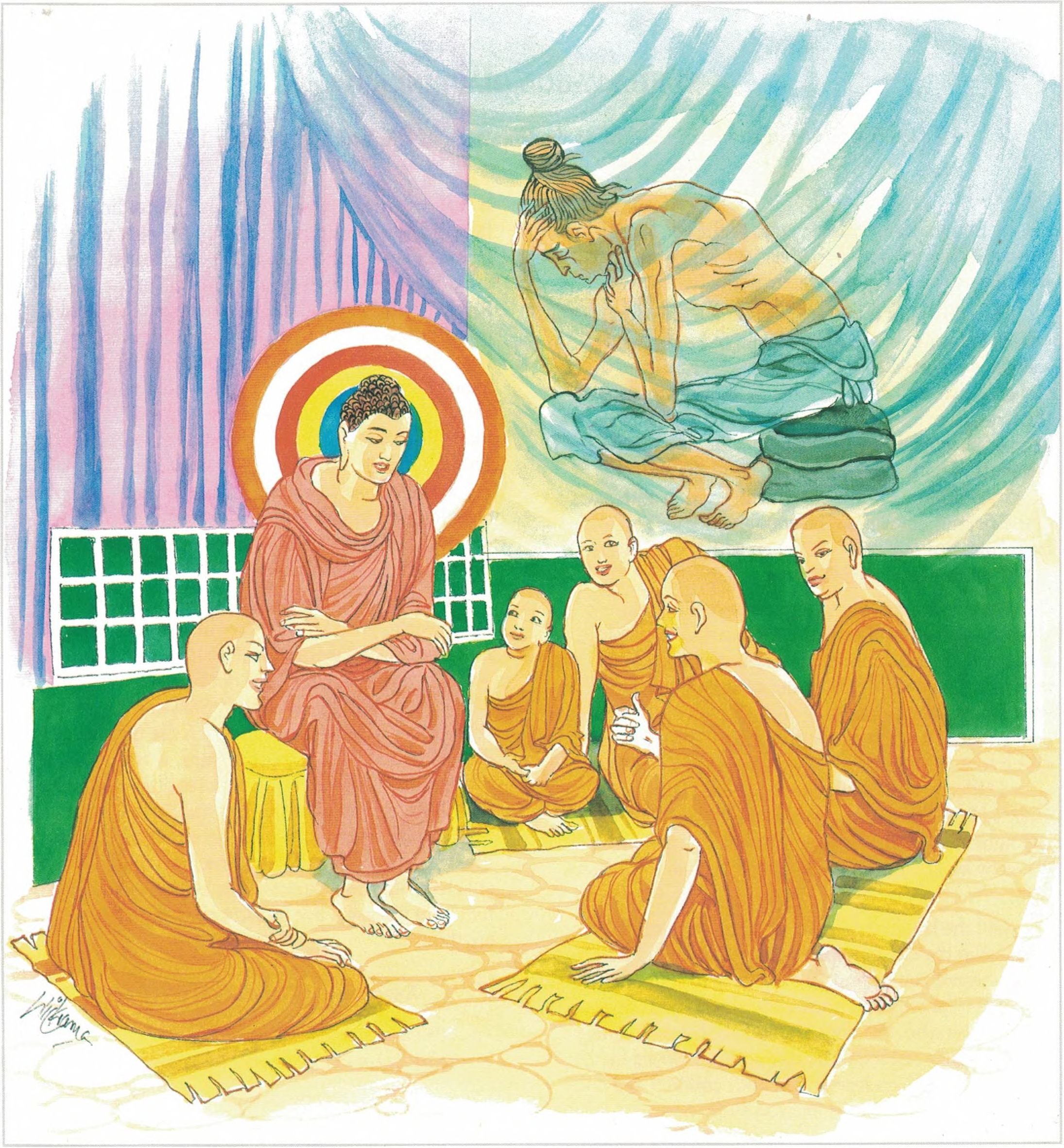

Innocent Rāhula came to the Buddha’s presence, and asking for his inheritance, as advised by his mother, very affectionately said, “O ascetic, even your shadow is pleasing to me.” After the meal, the Buddha left the palace and Rāhula followed Him, saying, “Give me my inheritance” and uttering much else that was becoming. Nobody attempted to stop him. Nor did the Buddha prevent him from following Him. Reaching the park the Buddha thought, “He desires his father’s wealth, but it goes with the world and is full of trouble. I shall give him the sevenfold noble wealth which I received at the foot of the Bodhi-tree, and make him an owner of a transcendental inheritance. He called Venerable Sāriputta and asked him to ordain little Rāhula.

Rāhula, who was then only seven years of age, was admitted into the Sangha.

King Suddhodana was deeply grieved to hear of the unexpected ordination of his beloved grandson. He approached the Buddha and, in humbly requesting Him not to ordain any one without the prior consent of the parents, said, “When the Buddha renounced the world it was a cause of great pain to me. It was so when Nanda renounced and especially so in the case of Rāhula. The love of a father towards a son cuts through the skin, (the hide), the flesh, the sinew, the bone and the marrow. Grant the request that the Noble Ones may not confer ordination on a son without the permission of his parents.” The Buddha readily granted the request, and made it a rule in the Vinaya. How a young boy of seven years could lead the religious life is almost inconceivable. But Sāmanera (novice) Rāhula, cultured, exceptionally obedient and welldisciplined as he was, was very eager to accept instruction from his superiors. It is stated that he would rise early in the morning and taking a handful of sand throw it up, saying, “Today, may I receive from my instructors as much counsel as these grains of sand.” One of the earliest discourses preached to him, immediately after his ordination, was the Ambalatthika-rāhulovāda Sutta in which He emphasized the importance of truthfulness.

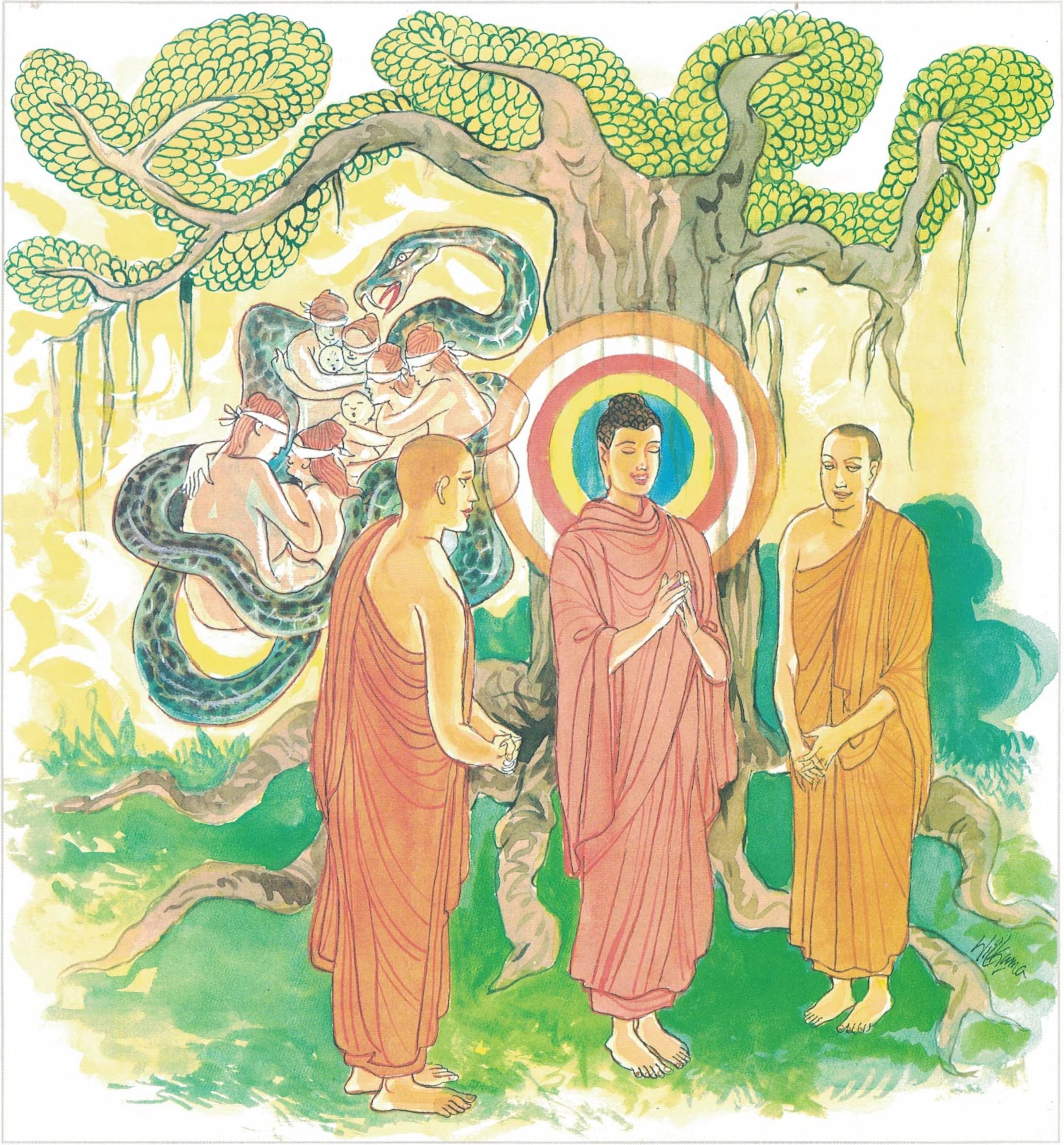

One day, the Buddha visited the Venerable Rāhula who, upon seeing Him coming from afar, arranged a seat and supplied water for washing the feet. The Buddha washed His feet and leaving a small quantity of water in the vessel, said, “Do you see, Rāhula, this small quantity of water left in the vessel?” “Yes, Lord.” “Similarly, Rāhula, insignificant, indeed, is the sāmanaship (monkhood) of those who are not ashamed of uttering deliberate lies.” Then the Buddha threw away that small quantity of water, and said, “Discarded, indeed, is the sāmanaship of those who are not ashamed of deliberate lying.” The Buddha turned the vessel upside down, and said, “Overturned, indeed is the sāmanaship of those who are not ashamed of uttering deliberate lies.”

Finally the Buddha set the vessel upright and said, “Empty and void, indeed, is the sāmanaship of those who are not ashamed of deliberate lying. I say of anyone who is not ashamed of uttering deliberate lies, that there is no evil that could not be done by him. Accordingly, Rāhula, thus should you train yourself. Not even in play will I tell a lie.”

Emphasizing the importance of truthfulness with such homely illustrations, the Buddha explained to him the value of reflection and the criterion of morality in such a way as a child could understand. “Rāhula, for what purpose is a mirror?” questioned the Buddha. “For the purpose of reflecting, Lord.” “Similarly, Rāhula, after reflecting and reflecting should bodily action be done; after reflecting should verbal action be done; after reflecting should mental action be done.”

“Whatever action you desire to do with the body, of that particular bodily action you should reflect: ‘Now, this action that I desire to perform with the body–would this, my bodily action be conducive to my own harm, or to the harm of others, or to that of both myself and others?’ Then, unskillful is this bodily action, entailing suffering and producing pain.”

“If, when reflecting, you should realize: ‘Now, this bodily action of mine that I am desirous of performing, would be conducive to my own harm or to the harm of others, or to that of both myself and others.’ Then unskillful is this bodily action, entailing suffering and producing pain. Such an action with the body, you must on no account perform.” “If, on the other hand, when reflecting you realize: ‘Now, this bodily action that I am desirous of performing, would conduce neither to the harm of myself, nor to that of others, nor to that of both myself and others.’ Then skilful is this bodily action, entailing pleasure and producing happiness. Such bodily action you should perform.” Exhorting the Sāmanera Rāhula to use reflection during and after one’s actions, the Buddha said, “While you are doing an action with the body, of that particular action should you reflect: ‘Now, is this action that I am doing with my body conducive to my own harm, or to the harm of others or to that of both myself and others?’ Then unskillful is this bodily action, entailing suffering and producing pain.”

“If, when reflecting, you realize: ‘Now, this action that I am doing with my body is conducive to my own harm, to the harm of others, and to that of both myself and others.’ Then unskillful is this bodily action, entailing suffering and producing pain. From such a bodily action you must desist.”

“If when reflecting, you should realize: ‘Now, this action of mine that I am doing with the body is conducive neither to my own harm, nor to the harm of others, nor to that of both myself and others.’ Then skilful is this bodily action, entailing pleasure and happiness. Such a bodily action you should do again and again.” The Buddha said, “If, when reflecting, you should realize: ‘Now, this action that I have done is unskillful.’ Such an action should be confessed, revealed, and made manifest to the Buddha, or to the learned, or to your brethren of the religious life. Having confessed, you should acquire restraint in the future. These various links and the urge to avert a meaningless war made the Buddha settle the conflict between the Sākyas and the Koliyas.