Dhammapada (Illustrated)

by Ven. Weagoda Sarada Maha Thero | 1993 | 341,201 words | ISBN-10: 9810049382 | ISBN-13: 9789810049386

This page describes The Story of Two Friends which is verse 19-20 of the English translation of the Dhammapada which forms a part of the Sutta Pitaka of the Buddhist canon of literature. Presenting the fundamental basics of the Buddhist way of life, the Dhammapada is a collection of 423 stanzas. This verse 19-20 is part of the Yamaka Vagga (Twin Verses) and the moral of the story is “Reciting Dhamma, without practice of it, is fruitless like a cowherd’s count of another’s cattle.” (first part only).

Verse 19-20 - The Story of Two Friends

Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 19-20:

bahumpi ce sahitaṃ bhāsamāno na takkaro hoti naro pamatto |

gopo'va gāvo gaṇayaṃ paresaṃ na bhāgavā sāmaññassa hoti || 19 ||

appampi ce sahitaṃ bhāsamāno dhammassa hoti anudhammacārī |

rāgañca dosañca pahāya mohaṃ sammappajāno suvimuttacitto |

anupādiyāno idha vā huraṃ vā sa bhāgavā sāmaññassa hoti || 20 ||

19. Though many sacred texts he chants the heedless man’s no practicer, as cowherd counting others’ kine in samanaship he has no share.

20. Though few the sacred texts he chants in Dhamma does practice run, clear of delusion, lust and hate, wisdom perfected, with heart well-freed.

Reciting Dhamma, without practice of it, is fruitless like a cowherd’s count of another’s cattle. |

Practice of Dhamma, with less of recital, totally unattached, qualifies one for recluseship. |

The Story of Two Friends

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke these verses, with reference to two monks who were friends.

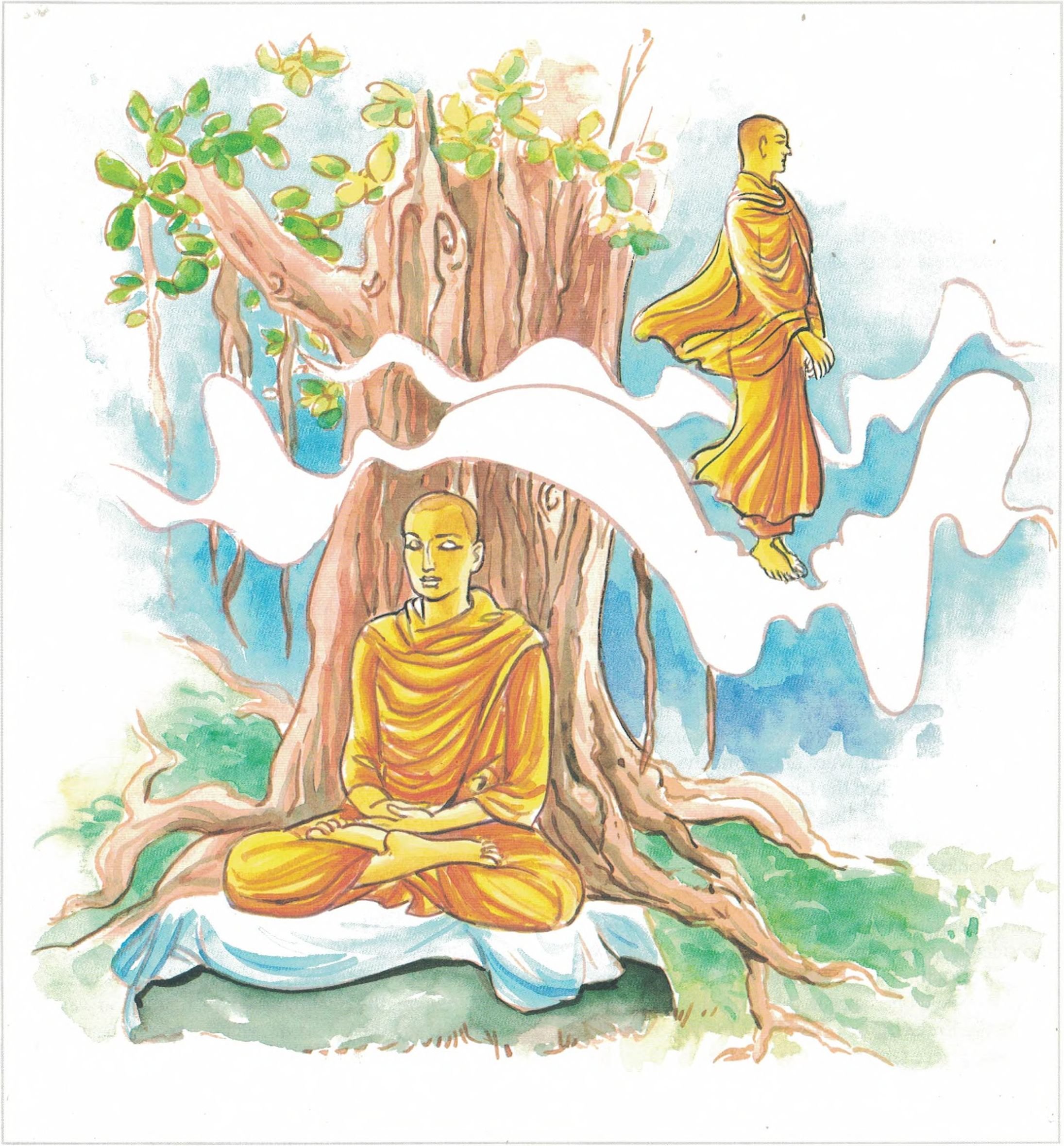

For at Sāvatthi lived two young men of noble family who were inseparable friends. On a certain occasion they went to the Monastery, heard the Teacher preach the Law, renounced the pleasures of the world, yielded the mind to the Religion of the Buddha, and became monks. When they had kept residence for five years with preceptors and teachers, they approached the Teacher and asked about the Duties in his Religion. After listening to a detailed description of the Duty of Meditation and of the Duty of Study, one of them said, “Venerable, since I became a monk in old age, I shall not be able to fulfill the Duty of Study, but I can fulfill the Duty of Meditation.” So he had the Teacher instruct him in the Duty of Meditation as far as Arahatship, and after striving and struggling attained Arahatship, together with the Supernatural Faculties. But the other said, I will fulfill the Duty of Study,” acquired by degrees the Tipitaka, the Word of the Buddha, and wherever he went, preached the Law and intoned it. He went from place to place reciting the Law to five hundred monks, and was preceptor of eighteen large communities of monks.

Now a company of monks, having obtained a Formula of Meditation from the Teacher, went to the place of residence of the older monk, and by faithful observance of his admonitions attained Arahatship. Thereupon, they paid obeisance to the Venerable and said, “We desire to see the Teacher.” Said the Venerable, “Go, brethren, greet in my name the Buddha, and likewise greet the eighty Chief Venerables, and greet my fellow-elder, saying, ‘Our teacher greets you.’” So those monks went to the Monastery and greeted the Buddha and the Venerables, saying, “Venerable, our teacher greets you.” When they greeted their teacher’s fellow-elder, he replied, “Who is he?” Said the monks, “He is your fellow-monk, Venerable.”

Said the younger monk, “But what have you learned from him? Of the Dīgha Nikāya and the other Nikāyas, have you learned a single Nikāya? Of the Three Pitakas, have you learned a single Pitaka?” And he thought to himself, “This monk does not know a single stanza containing four verses. As soon as he became a monk, he took rags from a dust-heap, entered the forest, and gathered a great many pupils about him. When he returns, it behoves me to ask him some question.” Now somewhat later the older monk came to see the Buddha, and leaving his bowl and robe with his fellow-elder, went and greeted the Buddha and the eighty Chief Venerables, afterwards returning to the place of residence of his fellow-elder. The younger monk showed him the customary attentions, provided him with a seat of the same size as his own, and then sat down, thinking to himself, “I will ask him a question.”

At that moment the Buddha thought to Himself, “Should this monk annoy this my son, he is likely to be reborn in Hell.” So out of compassion for him, pretending to be going the rounds of the monastery, He went to the place where the two monks were sitting and sat down on the Seat of the Buddha already prepared. (For wherever the monks sit down, they first prepare the Seat of the Buddha, and not until they have so done do they themselves sit down).

Therefore, the Buddha sat down on a seat already prepared for Him. And when He had sat down, He asked the monk who had taken upon himself the Duty of Study a question on the First Trance. When the younger monk had answered this question correctly, the Teacher, beginning with the Second Trance, asked him questions about the Eight Attainments and about Form and the Formless World, all of which he answered correctly. Then the Teacher asked him a question about the Path of Conversion; he was unable to answer it. Thereupon, the Buddha asked the monk who was an Arahat, and the latter immediately gave the correct answer.

“Well done, well done, monk!” said the Teacher, greatly pleased. The Teacher then asked questions about the remaining Paths in order. The monk who had taken upon himself the Duty of Study was unable to answer a single question, while the monk who had attained unto Arahatship answered every question He asked. On each of four occasions the Buddha bestowed applause on him. Hearing this, all the deities, from the gods of earth to the gods of the World of Brahma, including Nāgas and Garudās, shouted their applause.

Hearing this applause, the pupils and fellow-residents of the younger monk were offended at the Buddha and said, “Why did the Buddha do this? He bestowed applause on each of four occasions on the old monk who knows nothing at all. But to our own teacher, who knows all the Sacred Word by heart and is at the head of five hundred monks, he gave no praise at all.” The Teacher asked them, “Monks, what is it you are talking about?” When they told Him, He said, “Monks, your own teacher is in my Religion like a man who tends cows for hire. But my son is like a master who enjoys the five products of the cow at his own good pleasure.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 19)

pamatto naro sahitaṃ bahuṃ bhāsamāno api ce

takkaro na hoti paresaṃ gāvo ganayaṃ gopo iva sāmaññassa bhāgavā na hoti.

pamatto [pamatta]: slothful; naro: person; sahitaṃ [sahita]: the Buddha’s word; bahuṃ [bahu]: extensively; bhāsamāno [bhāsamāna]: recites; api: though; ce: yet; takkaro [takkara]: behaving accordingly; na hoti: does not become; paresaṃ [paresa]: of others; gāvo: cattle; ganayaṃ [ganaya]: protecting; gopo iva: cowherd like; sāmaññassa: the renounced life; bhāgavā na hoti: does not partake of.

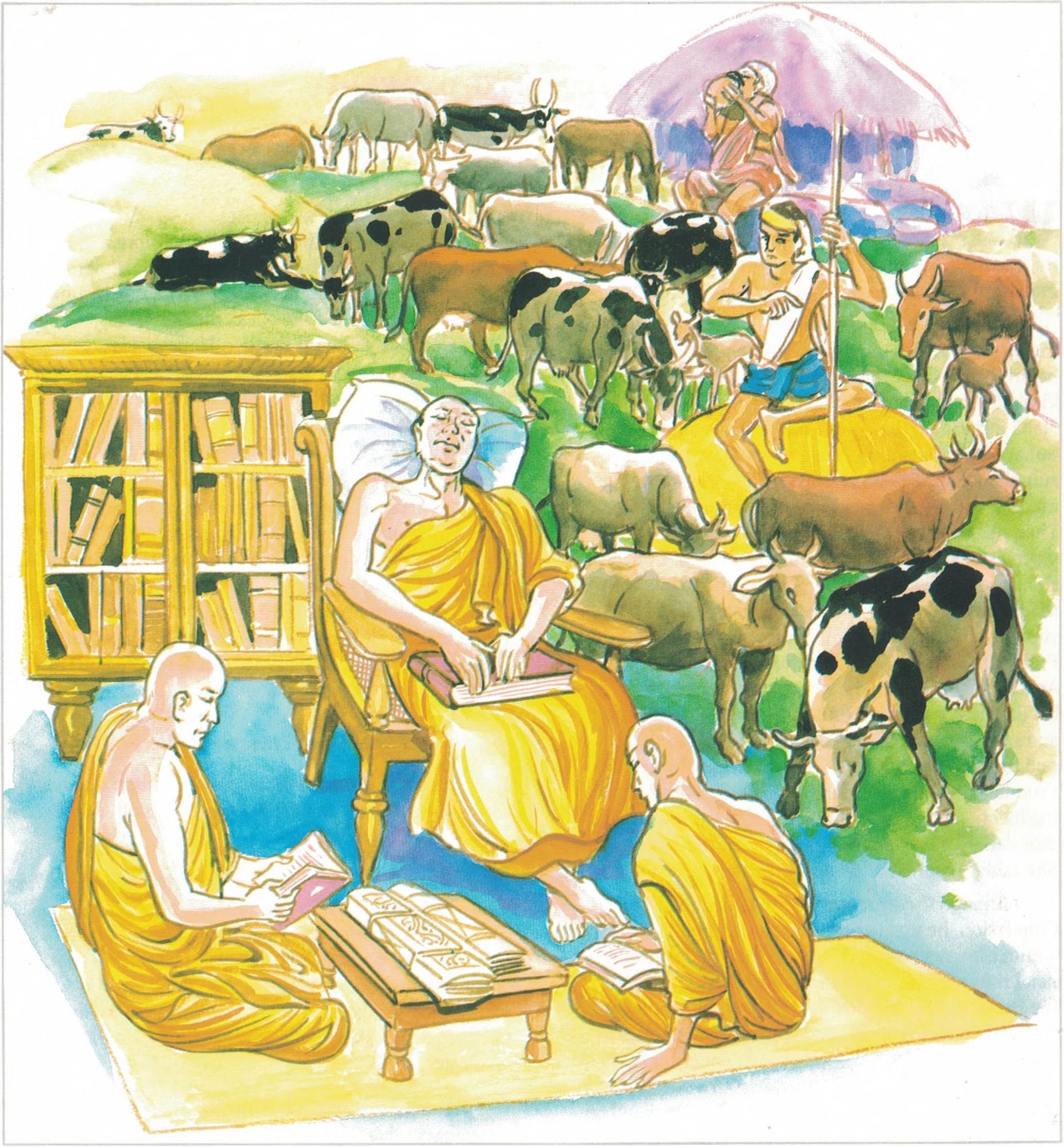

Some persons may know the word of the Buddha extensively and can repeat it all. But through utter neglect they live not up to it. In consequence they do not reach any religious attainments. He enjoys not the fruits of recluse life. This is exactly like the way of life of a cowherd who looks after another’s cattle. The cowherd takes the cattle to the pasture in the morning, and in the evening he brings them back to the owner’s house. He gets only the wages.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 20)

sahitaṃ appaṃ api bhāsamāno ce dhammassa

anudhammacārī hoti rāgaṃ ca dosaṃ ca mohaṃ

ca pahāya so sammappajāno suvimuttacitto idha

vā huraṃ vā anupādiyāno sāmaññassa bhāgavā hoti.

sahitaṃ [sahita]: the word of the Buddha; appaṃ api: even a little; bhāsamāno [bhāsamāna]: repeating; ce: if; dhammassa: of the teaching; anudhammacārī hoti: lives in accordance with the teaching; rāgaṃ ca: passion; dosaṃ ca: ill-will; mohaṃ ca: delusion; pahāya: giving up; so: he; sammappajāno [sammappajāna]: possessing penetrative understanding; suvimuttacitto [suvimuttacitta]: freed from emotions; idha vā: either here; huraṃ vā: or the next world; anupādiyāno [anupādiyāna]: not clinging to; sāmaññassa: of the renounced life; bhāgavā hoti: does partake of.

A true seeker of truth though he may speak only little of the Buddha’s word. He may not be able to recite extensively from religious texts. But, if he belongs to the teaching of the Buddha assiduously, lives in accordance with the teachings of the Buddha, if he has got rid of passion, ill-will and delusion, he has well penetrated experience and is free from clinging to worldly things, he is a partaker of the life of a renunciate.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 19-20)

sahitaṃ: literally this means any literature. But in this instance, the reference is specifically to the Buddhist literature. The Word of the Buddha is enshrined in the Three Baskets (pitakas). This stanza emphasizes the fact that the mere reciting of the word of the Buddha is not going to make much of a difference in the religious life of a person if the truth-seeker is not prepared to practice what is being recited. The fulfillment of religious life is ensured only if the person organizes his life according to what has been said by the Buddha. The effort of the person who merely recites the word of the Buddha is as futile as the activity of the cowherd who takes the trouble to count others’ cattle while the dairy products are enjoyed by someone else–the owner. The stanza refers to a person who was very much learned in the literature of Buddhism, but had not practiced what was said in it.

suvimutta citto: freed from emotions. An individual who has freed himself from clinging and grasping attains the total emotional freedom.

anupādiyāno: An individual who has ended the habit of clinging and grasping to this world and the next.