The civilization of Babylonia and Assyria

Its remains, language, history, religion, commerce, law, art, and literature

by Morris Jastrow | 1915 | 168,585 words

This work attempts to present a study of the unprecedented civilizations that flourished in the Tigris-Euphrates Valley many thousands of years ago. Spreading northward into present-day Turkey and Iran, the land known by the Greeks as Mesopotamia flourished until just before the Christian era....

Part XIV

In Assyria we find bronze gradually supplanting the use of copper, though copper also continued in use to the latest period. Among the large variety of bronze objects discovered in Assyrian mounds a series of bronze weights in the shape of animals arrest our attention by the admirable drawing of the body and head of the lions. [1]

It is clear, of course, that such objects were cast by means of moulds, and presumably in the case of large and heavy objects, the moulds were of stone or of bronze, while for smaller objects clay moulds probably served as a more convenient and also a simpler method.

PLATE LXVI

Figs. 1 and 2, Bronze plaque (obverse and reverse) showing exorcising ceremony

PLATE LXVII

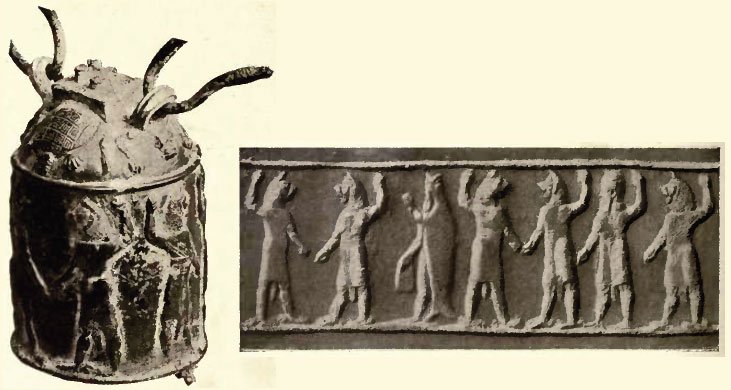

Fig. 1 (left), Babylonian bronze bell

Fig. 2 (right), Demons on bronze bell

A high degree of art is reached in repousse work and engraving on bronze. Of the former art we fortunately have some remarkable specimens in strips of bronze discovered at Balawat the site of an Assyrian town, Imgur-Bel some fifteen miles southeast of Nineveh and which were originally attached to large wooden gates belonging probably to the palace erected by Shalmaneser III. (858-824 B.C.), at that place. [2]

The doors themselves were over twenty feet high, six feet wide and three inches thick. The scenes represented on the bronze strips were intended to illustrate the campaigns of the king. The method followed was to beat out the designs on the reverse, and then to finish it off with a graver on the right side. There are indications of the hands of several artists in the work, for some of the strips are superior in workmanship to those on others.

The chief defect is in the lack of perspective, which makes itself felt when large numbers of personages are represented together and who thus appear to be closely crowded; but considering the difficulties involved in the indication of details, it is remarkable with what skill the camp life of the Assyrian army and the same army in action is brought before us, and this despite the fact that the animals, more particularly the horses, are depicted in a very conventional fashion.

On the other hand the groups of marching men soldiers and prisoners are frequently full of life and vigor, as are the scenes depicting the attacks upon the walled cities of the enemy and the camp scenes which are valuable also as illustrations of details in the life of an Assyrian army.

The finest specimens, however, of the work of the engraver on metal are a number of remarkable bronze bowls found at Nimrud. The designs repeated like a pattern are series of animals, gazelles, bulls, lions, ibexes, depicted with remarkable vividness, or griffins standing before a sacred pole, the execution of which is particularly delicate (Plate LXX). An interesting feature of these bowls is the indication of foreign influence which raises indeed the question whether they are native Assyrian work.

The griffins with the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt on their heads are distinctly Egyptian, but on the other hand the forms of the poles agree with designs found in Babylonian-Assyrian seal cylinders. Some of the platters also contain inscriptions in Phoenician characters, a circumstance that may be due to the spread of Aramaic in Babylonia and Assyria during the eighth and seventh centuries for which there is other evidence. [3]

The animals above referred to are precisely the ones which we find on older Babylonian works of art, and when, in addition, we encounter so genuinely Babylonian a design as the conflict between bulls and lions on the bronze bowls, there can scarcely be any doubt that we are in the presence of native work, which in the later centuries of Babylonian-Assyrian history was particularly subject to foreign influences.

PLATE LXVIII

Figs. 1 and 2, Bronze coverings on palace gates at Balawat

PLATE LXIX

Figs. 1 and 2, Bronze coverings on palace gates at Balawat

The wide use of bronze for the manufacture of ornaments such as rings, bracelets, trinkets and amulets or talismans is illustrated by many specimens, though it cannot be said on the basis of what has been found that a high degree of artistic perfection was reached until we come to the Persian period when new influences found their way into Mesopotamia.

Gold and silver were also largely used for ear-rings, necklaces, [4] for inlaid work and as coverings for ceilings and walls in part or for royal thrones, while it did not appear to be even unusual for statues of gods to be made entirely of gold.

A Babylonian ruler of the middle of the ninth century, Nabupaliddin, tells us that he prepared a statue of Shamash, the sun-god, made of gold and lapis lazuli, and there are good reasons for believing that the image of the chief god Marduk which stood in his temple at Babylon was entirely of gold. At Ashur the explorers found the remains of a gold lightning fork which had been placed in the hands of the life-size statue of the storm god Adad.

We are fortunate in possessing a specimen of the silversmith's art, all the more remarkable because of its antiquity (Plate LXXI). It was found at Lagash and was a dedicatory offering of Entemena (c. 2850 B.C.). Resting on a copper base, supported by four lions' feet, the vase stands 28 inches above the base.

The shape is most graceful, but what adds to its artistic merit is the delicate engraving running around the centre of crouching heifers and of four fantastic eagles with human heads, clutching lions and ibexes alternately. The upper row of seven heifers is particularly well executed, in contrast to the grotesqueness of the lions and to the stiff conventionalism of the ibexes. On the other hand, there is a certain dignity in the eagle with the human face, the symbolism of which is of the same general character as in the case of the winged creatures standing before the sacred tree.

Significant, however, in the case of all the figures on the silver vase is the delicacy of the work, in which respect it has rarely been excelled in works of art coming down to us from antiquity.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

See e.g., Mansell, British, Museum Photographs No. 585 and Layard, Monuments of Nineveh, 1st Series, PL 96.

[2]:

Birch & Pinches, The Bronze Ornaments of the Palace Gates of Balawat (London, 1880) ; and Billerbeck and Delitzsch, Die Palasttore Salmanassars II van Balawat (Beitrage zur Assyriologie, vi, pp. 1-155 and 4 plates). See Plate LXVIII and LXIX.

[3]:

We find on. business documents of Assyria and Babylonia from the eighth to the fourth century endorsements in Aramaic. See Clay, Some Aramaic Endorsements on Documents of Murashu Sons in Harper Memorial Studies, vol. i, pp. 285-322.

[4]:

A particularly fine specimen of an early Babylonian gold necklace in private possession is pictured in Meissner, Grundzuege der altbabylonischen Plastik, p. 64 (Alte Orient, xv, Heft 1 and 2). See also Botta et Plandin, Monument de Ninive, Vol. II, PI. 161 and Handcock, Mesopotamia, Archceology, p. 348.