The civilization of Babylonia and Assyria

Its remains, language, history, religion, commerce, law, art, and literature

by Morris Jastrow | 1915 | 168,585 words

This work attempts to present a study of the unprecedented civilizations that flourished in the Tigris-Euphrates Valley many thousands of years ago. Spreading northward into present-day Turkey and Iran, the land known by the Greeks as Mesopotamia flourished until just before the Christian era....

Part VII

The progress of sculptural art is to be seen in the direction of an advancing complication in the design so as to tell as full and detailed a story as possible. The best specimen in this respect so far recovered is a large limestone stele, unfortunately found in a broken condition, but of which enough is preserved to make clear the various episodes in a great struggle which it illustrates.

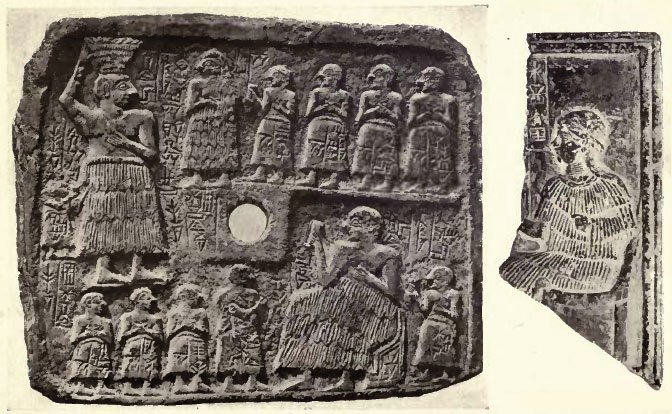

PLATE XLVI

Fig. 1 (left), Ur-Nina, King of Lagash (c. 300 B.C.), and his family

Fig. 2 (right), The Goddess Ninsun

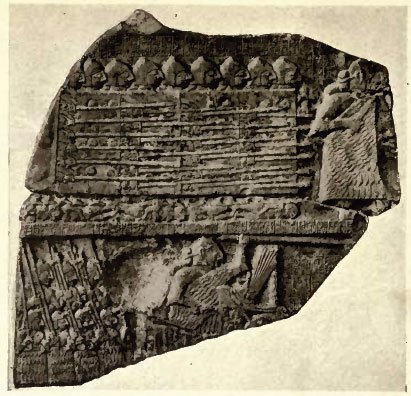

PLATE XLVII. FRAGMENTS OF THE "STELE OF VULTURES"

Fig. 1, The army of Eannatum, ruler of Lagash (c. 2920 B.C.)

Fig. 2, The God Ningirsu, capturing the enemies of Lagash in his net

The remarkable monument found at Telloh dates from the reign of Eannatum (c. 2920 B..C.) and portrays his successful engagement against the people of Umma with whom the rulers of Lagash had many a passage at arms. [1] Eannatum pictures the great god of Lagash, Ningirsu, as capturing the forces of the enemy in a large net. This symbolism is offset by a no less remarkable realism in portraying the course of the battle and its issue. One of the fragments, divided as usual into two compartments, shows the troops of Eannatum actually engaged in the conflict.

The king is clad in a long skirt to which a cloak falling over the left shoulder is attached. The king's helmet differs also from the head gear of the soldiers by the ear-pieces with which it is provided. In his right hand he holds a weapon which has the shape of a boomerang. The march of the troops over the prostrate bodies of the enemy is portrayed with remarkable vividness and power. They form a solid phalanx, with their long lances held in the right hand, while with the left they protect themselves by rectangular shields that cover the entire body.

To illustrate the various divisions of the soldiery participating in the battle, the "light" infantry is shown in the lower compartment, armed with lances and battleaxes but without shields. Again the king is portrayed at the head of his army, but this time riding in a chariot and brandishing a long lance to suggest another stage in the engagement, which probably extended over a considerable period of time.

The entire obverse of the monument appears to have been taken up with the portrayal of the attack and the various stages in the engagement, while the reverse illustrated the result of the battle. Just as the king, to symbolize his preeminent rank, is drawn as of larger stature than his soldiers, so the god Ningirsu is pictured as huge even in comparison with the king. The upper part of the head is wanting, but despite this, one is struck by the great dignity of the face, which is drawn with evident care. The eye is majestic, the mouth firm, while the long flowing beard adds to the impressiveness of the figure. In his right hand Ningirsu holds a powerful mace as his weapon, while in his left he clasps the heraldic standard of Lagash, the eagle holding two lions in his talons.

This standard is frequently portrayed on seal cylinders and other works of art, and well illustrates again the symbolism that finds an expression in such various ways in the oldest art of the Euphrates Valley. The central idea of the design is strength strength in a superlative degree. Before the god is the huge net with the prisoners to symbolize the capture of the enemy. To further indicate the impossibility of escape from the clutches of Eannatum, a prisoner who has thrust his head out of one of the meshes is being beaten back by the weapon in the hand of the god.

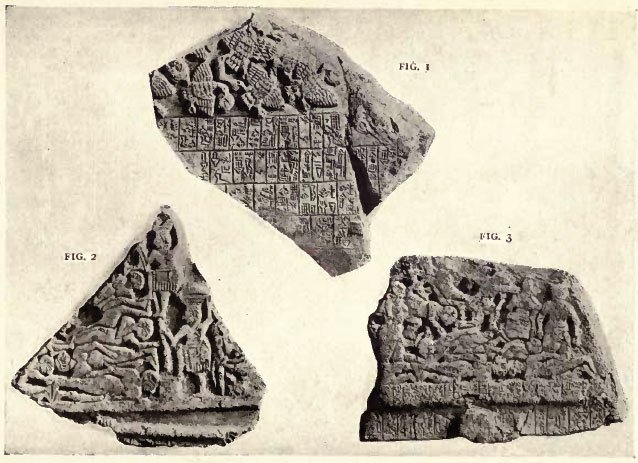

The same combination of symbolism with extreme realism so extreme as to be almost naive marks two other fragments of this monument continuing the tale of the victory and its results. One of these shows several rows of corpses, naked and with shaven heads, but evidently arranged in a certain order with great care. The burial of the soldiers of Eannatum who had fallen in battle is here depicted, by way of contrast to the scene preserved in part on the other fragment, showing vultures flying off with human heads, clearly intended to symbolize the punishment meted out to the slain forces of the enemy [2] (Plates XLVII and XLVIII).

PLATE XLVIII, FRAGMENTS OF THE "STELE OF VULTURES"

Fig. 1 (left), Heads of enemies carried off by vultures

Fig. 2 (top), Burial of soldiers of Eannatum

Fig. 3 (right), The confict between Lagash and Umma

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

See above, p. 128 seq.

[2]:

Because of this fragment the monument is commonly designated as the "Stele des Vautours" ("Vulture Stele"). See for further details, Heuzey et Thureau-Dangin, Restitution materielle Stele des Vautours (Paris, 1911).