The civilization of Babylonia and Assyria

Its remains, language, history, religion, commerce, law, art, and literature

by Morris Jastrow | 1915 | 168,585 words

This work attempts to present a study of the unprecedented civilizations that flourished in the Tigris-Euphrates Valley many thousands of years ago. Spreading northward into present-day Turkey and Iran, the land known by the Greeks as Mesopotamia flourished until just before the Christian era....

Part V

The story of how the palaces and temples of Assyria and Babylonia with their rich and varied contents were brought to view through the untiring energy of a long series of explorers, is a most fascinating one. Beginning in 1842 with the work of P. E. Botta at the mounds opposite Mosul and continuing to our own days the great museums of Europe and this country more particu- larly the British Museum, the Louvre, the Berlin Museum, and the Archasological Museum of the University of Pennsylvania, bear witness to the vast material that has been brought together in the space of seventy years and of which so large a part has now, through publications, been placed at the disposal of students. [1]

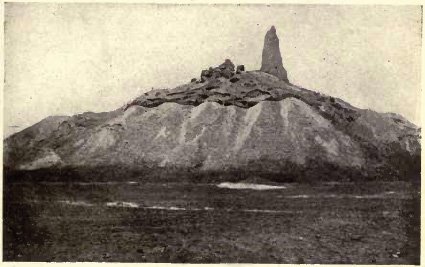

The PLATE III

Fig. 1, Mound and Village of Khorsabad

Fig. 2, Birs Nimrud, the site of Borsippa

Botta, appointed consular agent of France at Mosul, in 1842, began work late that year on a large mound Kouyunjikon the Tigris opposite Mosul, and which, like the neighboring heap, Nebbi Yunus, covered a portion of the ancient city of Nineveh. In beginning excavations at these large mounds it was at first largely guesswork where to dig the first trenches, and it depended upon chance whether one's efforts were rewarded with tangible results. Botta worked at Kouyunjik for some months with only moderate success. Inscriptions and bas reliefs were found, but in a fragmentary condition and nothing that appeared to be particularly striking.

He accordingly, in March, 1843, transferred the scene of his operations to a mound Khorsabad, a short distance to the north of Kouyunjik, where he was almost immediately successful in coming upon two mutilated walls covered with sculptured bas-reliefs, accompanied by inscriptions in the ordinary cuneiform character. There could be no question that he had actually come across a portion of an Assyrian building and ere long a whole series of rooms had been unearthed filled with monuments of the past.

The announcement of these discoveries created tremendous excitement, and soon sufficient funds were placed at Botta's disposal to enable him to carry on his work on a large scale. An artist, E. Flandin, was dispatched to sketch the monuments that could not be removed and to draw plans of the excavations. By October, 1844, a large portion of the palace for such the edifice turned out to be had been excavated, revealing an almost endless succession of rooms, the walls of which were covered with sculptured bas-reliefs. These sculptures were of the most various character.

Long processions of marching soldiers alternated with scenes illustrative of life in military camps showing the horses, chariots and tents and the method of attack upon the enemy the approach to the walls, the actual conflict, the capture of a town, and the carrying away of captives. Hunting scenes were represented in equally elaborate fashion, showing the king in his chariot, surrounded by his attendants.

Lions were depicted in the act of being let out of their enclosures, or attacked by the royal hunter. There followed a procession of servants carrying the dead lions, as well as game of a smaller character. A notable feature of the excavations were the huge winged bulls with human heads that were found at the entrances leading to the great halls. The bodies of these bulls were covered with cuneiform inscriptions which when they came to be deciphered told in general outlines of the achievements of the monarch who had erected this large palace for himself, namely, Sargon II, who ruled over Assyria from 725 to 706 B.C.

As much of the vast material as possible was placed on rafts and floated down the Tigris to Basra whence it was safely carried by a French man-of-war to Havre. The antiquities were brought to the Louvre, while the detailed results of the expedition were set forth in five large folio volumes containing the drawings of Flandin, no less than 400 plates, with detailed descriptions by Botta. [2]

The great value of the remarkable discoveries stimulated further interest in France; in 1851 a second expedition was fitted out by a vote of the French Assembly. This expedition, which extended its labors to mounds in the south, was placed under the leadership of Victor Place, a trained architect, who had been appointed Botta's successor as consular agent in Mosul.

PLATE IV

Fig. 1, Hunting Scene (Khorsabad)

Fig. 2, Procession of Captives, Bearing Tribute (Khorsabad)

Place's architectural skill enabled him to carry on the work more systematically, and demonstrated the advantage of having an architect to conduct excavations of ancient buildings. He unearthed many more rooms of the palace, and passing beyond this building, came across a number of large gates, decorated with enamelled tiles in brilliant colors forming ornamental designs, and pictures of fantastic animals.

The large courts of the palace were laid bare and several smaller buildings which, as was subsequently ascertained, represented temples. Large quantities of pottery and objects of stone, of glass and metals were found, as well as iron implements in an excellent state of preservation, and even the magazine in which the colored tiles were stored. In an elaborate publication, [3] Place embodied the results of his successful labors, on the basis of which he attempted to reconstruct the greater portion of the edifices he had unearthed. The mounds at Khorsabad, it thus resulted, represented a fortified town erected by Sargon II, and which was known as Dur-Sharrukin, i.e., "Fort Sargon", as we may render the term.

Surrounded by walls with eight gates, the site covered an area of some 750 acres. The central building was the royal residence, erected on a high terrace and surrounded by a number of smaller buildings for the use of the royal court. The building material was stone for the exterior walls, and in part for the floors, but for the greater part of the structure baked and unbaked bricks, which constituted the ordinary material used in the buildings of Babylonia and Assyria, were employed.

Place also extended his excavations to other mounds not far from Mosul, such as Kaleh-Shergat (the site of the ancient city of Ashur) and Nimrud (the site of Calah) besides carefully examining many other mounds, but without the same success that attended his and Botta's efforts at Khorsabad. Unfortunately the antiquities selected by Place for shipment to Paris were lost through the sinking of the two boats on which they were placed.

Drawings and copies had, however, been made of all of them, so that the loss to science was not as great as it might have been. At the same time another French expedition under the leadership of Fresnel was busy conducting excavations in the south on one of the mounds that covered the city of Babylon, and which lasted until 1855. Before, however, taking up an account of the excavations on mounds in Babylonia, we must consider work done simultaneously with Place's excavations at Khorsabad by an English explorer who was destined to acquire even greater renown than either Botta, Flandin, or Place.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

For detailed accounts of excavations at Babylonia and Assyrian mounds, the reader is referred to Rogers' History of Babylonia and Assyria (New York, 1900), vol. i, pp. 1-174; to Hilprecht, Exploration in Bible Lands, (Phila., 1903), pp. 1-577; and to Possey, Manuel d'Assyriologie, vol. i (Paris, 1904).

[2]:

P. E. Botta et E. Flandin, Monument de Ninive (Paris, 1849-1850),5vols.

[3]:

Victor Place, Ninive et I'Assyrie, avec des .Essais de Restauration par Felix Thomas (Paris, 1867-1870) , 3 vols.