From under the Dust of Ages

by William St. Chad Boscawen | 1886 | 41,453 words

A series of six lectures on the history and antiquities of Assyria and Babylonia, delivered at the British Museum....

Lecture 2 - The Creation Legends

THE position occupied by the cosinogonic legends of an ancient people in their sacred literature is one which is often mistaken. Instead of being the earliest products of the pens of the priest scribes, they are often the latest, or at the least, of a period when the religious belief of the people had attained some considerable degree of development.

The examination of the series of legends, which form the subject of this afternoon's lecture, shows them rather to occupy the position of the literature of a period in the growth of religion in Babylonia, when the weird magical Animism of the Akkadians had become influenced by and blended with the purer creed of the Semetic settlers in Chaldeo, and out of this fusion was growing up that great and powerful religious system of the Chaldean people.

The sacred literature of Chaldea offers many advantages to the student of the origin and development of religious beliefs, not obtainable from the study of other systems. There has been preserved to us in the large series of magical litanies and incantations the books of that creed of Animism, which the Akkadians had brought with them from their mountain home. In that creed we find traces of the child-like efforts of these primitive people to solve the problems of their own existence.

Having, by comparison with the human body in sleep and death, arrived at the theory that all being was due to the presence of an indwelling spirit or power, called by them Zi — " life " or " breath," which was temporarily absent in sleep, but never returned in case of death, they proceeded to apply this theory of Animism to the world of nature.

The wind, the trees, clouds, the rivers, streams, the sun, moon, and stars, became the abodes of so many indwelling spirits, to whom all their movements and actions were due. This spirit-world soon became divided into two parties of good and evil spirits — those who were beneficial or malevolent to man, and thus the stage of dualism was reached. In course of time, as man proceeded with his study of the phenomena of nature, and their relation to one another, the various elements became grouped — a result which was only attained by long and close observation.

The clouds, sun, moon, and stars became the elements, ruled by the great Spirit of Heaven, as the streams, rivers, and metals formed the Kingdom of the Spirit of the underworld. It is evident, from the study of the inscriptions of this Eeligio-Magical creed, that the purer creed of the Semites from their desert home in Arabia exercised a powerful influence in the work of simplification.

The ruling spirits now became gods, and the pantheon was rapidly assuming order and system. A second element, which exercised a powerful influence in the development of the creation legends, was that of the relationship between Light and Darkness. To these ancient thinkers, Darkness was the womb out of which Light came — the mother of all things. Trees, flowers, animated existence of all kinds, were, by the aid of Light, brought forth from the enthralling power of Darkness. It was from this idea of the great primeval night that the idea of that state of chaos which existed before the work of creation had begun was developed.

Of the various series of cosmogonic legends of ancient religious systems, three have always been prominent as the most systematic and highly developed — the Hebrew version as contained in the Book of Genesis, the Chaldean as preserved in the writings of the Greco-Chaldean historians, Berossus and Damascius, and the Phoenician cosmogonic fragments preserved by Sanchoniatho.

In each of these three Western Asiatic systems, we find points in common, which, if they do not indicate a common parentage, at least show striking similarity of thought. The fragmentary and late version of the Chaldean creation legends, which had come down to us in the few quotations from the Books of Berossus, bore a very close resemblance to the opening chapters of the Mosaic Books.

This resemblance is found to be still more striking, now that we can compare the Hebrew version with the older and original tablets from which Berossus had derived his version. Ten years have now elapsed since Mr George Smith, by the discovery of these important tablets, added additional laurels to the wreath he had already gained by the discovery and decipherment of the Deluge tablet.

During that time, Assyriology has made great and important advances. In England, such students, as Professor Sayce and M. M. Pinches and Budge, have brought their knowledge to bear upon this important section of Assyrian literature ; while, on the Continent, Schracler, Delitzsch, Oppert, and Lenormant have also devoted much study to these legends.

The result has been that hidden meanings and niceties of expression, not recognised by the " too soon lost " discoverer, have been brought out, and the work of comparison can now be carried out with much more favourable results. Even at the very commencement of our study of these inscriptions, we are met by a small fragment of external evidence, striking in its similarity to the Hebrew version.

The system under which the tablets are arranged is by naming the series after the openingwords of the first tablet of the series. The first tablet, of which we possess a portion, commences with the words Bwum Mis, " In the time when above." And so we find Tablet V. of the series numbered by the Assyrian scribes as "Tablet V. Enuva Mis" deriving its name in the same manner as the First Book of Moses is called in the Hebrew Beresheth, or in the Greek Genesis, from its opening words. Of the tablets of this series, we have now portions of four, three of which are, strictly speaking, creation legends — the fourth, of which we have Loth Babylonian and Assyrian editions, being, as Mr Budge has pointed out, a poem describing the war in heaven.

Tablet I:

- In the time when above the heavens were unnamed (and),

- Below for the earth a name was not recorded.

- The limitless abyss, the first-born, was around them.

- The chaotic sea was the genetrice of them all.

- Their waters were joined in one.

- No crop had been gathered ; no flower had opened.

- In the time when as yet none of the gods had come forth.

- By name they were not named ; order [did not exist].

- The great gods were then made.

- The gods Lakhmu and Lakhamu caused themselves to come forth, and they spread abroad.

- The gods Assar and Kisar [were made].

- They were prolonged many days.

- The gods Ann (Bel and Hea, were born),

- The gods Assar and Kissar.

A very casual examination of this fragment is sufficient to reveal its importance, both as affording a striking resemblance to the cosmogonic legends of the Phoenicians and of the Hebrews. It is evident that, like the Hebrew tradition, the Chaldean contained the same idea of the existence of the earth prior to the commencement of the work of creation, in a state of chaos and darkness. This conception is hardly so fully apparent from the rendering of the opening verses of Genesis in our authorised version

" In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth : and the earth was without form and void, and darkness was upon the face of the deep ; "

as the words tohu va bohu admit of a more definite rendering than <; without form and void," as may be seen when we compare passages in which the former word occurs, and also by comparison with Assyrian inscriptions. In Deuteronomy xxxii. 10 —

" He found him in a desert land, and in a waste-hoivling wilderness ;"

and in Job xxvi. 7. we have two examples of this word —

" He stretcheth out the north over the enqrty ylace ;"

and in Job vi. 18, where our version again requires emendation, to read —

"The caravans turn aside on their way ; they go into the desert and perish."

From the comparison of these passages, it is evident that we must adopt, as a better rendering in this passage, " desert " in the place of " without form." Upon the second word, the Assyrian inscriptions throw some light. One of the most important goddesses of the Babylonian pantheon was the goddess called Balm. She was the spouse of the water god Hea, aud was the goddess who presided over the south of Babylonia, the region of the marshes. She bore the title of the " great mother," the " noble lady," the " bearing mother of mankind;" and, in her ancient nature-form, she was the goddess of the marshy stagnant wastes.

She assumes many of the attributes of the goddess mentioned in this creation tablet — Mumu Tiamat, the Chaotic Sea, the mother of all nature. We may therefore assume that the rendering of the opening words of Genesis may be taken as —

" Then the earth was desert and waste (or marsh)."

If we turn to the Assyrian tablet, we see how this idea is substantiated —

" The waters were joined in one ; no crop had been gathered, no flower had opened."

The word used here for gathered. Kitstsura, from Katsaru, " to bind or collect " [1] — gives the key to the meaning of the first word, which is unfortunately an apax legoncnis. The word used for flower -is the word usually employed for lily or marsh plant, and so the simile is preserved.

" The crop had not been gathered ;"

The earth was like the unproductive desert, and even the marsh land had not borne its typical flower, " the lily " — all was desert and waste. Such was the state of nature, and around all was the Absu, or " limitless sea of space." It is somewhat difficult to ascertain the exact nature of this very important element in the Chaldean theogony. In the version of this tablet, given by the Greek Neoplatonic writer, Damascius ! (Hodges Cory., p. 92), we read —

" The Babylonians, like the rest of the barbarians, pass over in silence the one priuciple of the universe, and they constitute two, Taute and Apason, making Apason the husband of Taute, and denominating her ' the mother of the gods.' From these proceeds an only-begotten son, Moymis ; from them also is derived other progeny — Dakhe and Dakhos, and again a third — Kissare and Assaros ; from the last of which three others proceed — Anus, Illinus, and Aus."

In both the cosmogonies of Damascius and of Sanchoniatho, the place of this Absu is the first in the work of creation. In some cases, Absu, as the tablets show, is to be identified with the yEtherial ocean, which circled round the world ; but in this inscription, as well as in some of the hymns, the priests and theologians of Chaldea have attributed a more philosophical meaning to it. In the Syllabaries we find the group Zu-ab explained by Absu, and an analysis of this Akkadian compound word affords some important light. The first element, Zu (No. 25 Sayce Sylb.), is explained by iclu, " to know," lamadu, " to teach," and by mucin, " knowledge," while the second, Ab (No. 44 Sayce Sylb.), is explained by bitu, " a house," or tiamtu, "the sea," or abu, "a cave." So that the whole compound word may mean " the house of knowledge " or " the sea of knowledge," and this we find confirmed by a beautiful Assyrian lit— any (W.A.I., vol. iv., p. lix., 34-35). We read Absu l((bdhur bit nimiki, " May Absu, the house of wisdom, pardon ;" and in the next line we read, Zukhi labdhur kabu absu, " May Zukhi, the depth of the absu, pardon," which at once may be read, " Oh, may Zukhi, the depth of the house of wisdom, pardon."

We may then compare with this explanation of this first-born of creation the following remarkable words in Proverbs viii. 21-27, "The Lord formed me in the beginning of his way, before his works of old. I was formed from everlasting, from the beginning, or ever the earth was. When there were no depths, I was brought forth ; when there were no fountains abounding in water. Before the mountains were settled, before the hills were brought forth. While as yet he had not made the earth, or the fields, or the beginning of the dust of the world. When he prepared the heavens I was there ; when he set a compass on the face of the deep." The comparison of these passages with the opening lines of the tablet almost compel us to adopt the more philosophical rendering oiabsu here as "wisdom."

Additional support is given to this rendering by comparing the Hebrew and Phoenician legends. The first-born in the cosmogony of Sanchoniatho by the union of Apason and Chaos is Desire, and we may compare with this the expression in Genesis i. 2, where our authorised version, as I have already said, misses the beauty.

"The breath or spirit of the Lord brooded on the face of the waters."

In the above extract the deep is rendered by Whom, the exact equivalent of the tiamat of the tablet. The " Spirit of God," the Rualh Elohim of the Hebrew writers has moreover in many places this philosophic sense of Divine Wisdom, as in Exodus xxxi. 3,

" Behold I have filled him with the Spirit of God, in wisdom and understanding and in knowledge ; "

and the attribute of prophecy is also frequently attributed to the Spirit, as in the case of the in- spiration of Balaam (Numb. xxiv. 2), of Saul (1 Saml. x. 6), the messengers of Saul (1 Saml. xix. 20, 23), and the Messiah (Isa. xlii. 1).

The comparison of these passages with the Assyrian Absu — the abode of knowledge — enables us to ascertain the reason that led the late ISTeoplatonic philosophers to make the mind or wisdom an important element in their theogonies.

In like manner the Chaotic sea — the Mummu Tiamat of the tablet — " the bearing mother of all," the Taute of Damascius, the Tisallat of Ilerossus, and the bride of Apason underwent many changes as the religion developed. Here she is called the genetrice or "bearing mother" of all; in the Cutha tablet she appears as the " mother " or "nurse" (iMLsewLk).

In the nature aspect of this character we see the dark watery sea of all-shrouding cloud which surrounded the earth — an aspect of her character, which, in later times, became that of the goddess Bahu, of whom I have already spoken. As the serpent coils round its eggs, so this chaos-serpent lay coiled round the earth, until slain by Merodach, the Lord of Light, who, like Apollo, went forth to slay the Python.

The representations which we have of this demon of Chaos show her as a woman with full breasts, like the Asiatic mother-goddess represented in a sculpture at Carchemish — or the Istar Nana of Babylonians and the Ephesian Diana, as denoting her character of the great Mother and Nurse of all. On a curious boundary-stone, dating from the 12 th century before our era, we have a very remarkable figure in which the serpent type is preserved, the body being that of a woman, the lower extremities replaced by the coiled tails of two serpents, like the figures in the sculptures of the Giganto-Machia at Pergamos. It was this Queen of Chaos who ruled while the earth lay like the cosmic egg in her coils, in the " time when as yet none of the gods had come forth."

We now come to the creation of the gods. It is important here to notice that the expression used of these two creations has a reflexive sense —

of self-creations " caused themselves to come forth;"

they "spread abroad."

These two deities, apparently male and female, are named Lakhmu and Lakhamu, and we must certainly identify them with the Dakhe and Dakhos of the cosmogony of Damascius.

At one time I was inclined to identify these creations with deifications of the light, and especially of the first pure light independent of sun or moon, the first work of the creator (Gen. i. 3). It is more probable now, I think, that that victory of the Divine Light over the power of darkness is represented in the tablet of the War in Heaven, which forms one of the books of this Creation series.

I was then inclined to think that the struggle between the two conflicting elements was embodied in the names of these gods, they meaning " the stragglers," from lakham, " to fight." It seems to me now that we have rather to take the names as Semitic, meaning "the dividers," and that they correspond to the division of nature into the terrestrial and celestial kingdoms — the Heaven being the firmament dividing the god-land from the Earth.

This identification seems to me, though not so fascinating as my former suggestion, to be more in accordance with the spirit of the text. It meets too with strong support from a bilingual list of gods (W. A. I., iii., pi. lxix., 14, 15), in which both these divinities are given as equivalent to the god Ann and his wife Anatu — the Chaldean Zeus and his wife — the deifications of the Heaven. Had they been deifications of the Light we should most probably have found them equated with the Sun god. The two realms of nature are now divided by the firmament ; and the next creation is that of the two creatures, Sar or Assar and Kiassar or Kisar — the Assor and Kissare of Damascius.

These are two compounds, words composed An-sar or " Heaven host " and Ki-sar, " Earth host," they being the host of Heaven and Earth, the spirit-forms afterwards known as the Annunaki and Ilgi; and upon this we have some light thrown in the expression in Gen. ii. 1. —

"Thus the heavens and the earth were finished — all the host of them."

The Annunaki or Spirits of Heaven in many ways resemble the Zabaoth-ha-shamaiu " of the Bible, which in many places cannot mean the stars.

The realm of nature is now so far ready for the three great gods to take possession, and we see the next step in the creation is that of the first trinity of the Babylonian Pantheon — Ann, Ellu or Bel, and Hea, the Aims Illinus and Aus or Oes of Damascius.

Of these three great gods little need be said ; their epithets mark them as a trinity having both a natural and a philosophical constitution. Ami is called " The Father of all the Gods," " The Progenitor, who changes not the decree coming forth from his mouth," " The Mighty Chief," " The Supreme, the Magnificent;' "The Lord of Heaven," "The Heaven."

In his character as a Nature-god we find him approaching near to the Vedic Varuna, the Greek Ouranos ; while in his religio-philosophic character, according to the Neoplatonicean school, he was the type of " the great father of all" — the Dyaus-pitar or Jupiter of the Pantheon. The second member, Bel or Elu, is a deity of great importance. His most frequent epithets are — " Lord of the world," " The Lord who guards his country," " Establisher of riches and wealth and possessions," "Lord of the lofty place."

This last epithet applies to his dwelling on the " Mount of the World — the Mountain of the East" — the Akkadian and Assyrian Olympus. One of his most interesting and important titles was that of Sadie rabu or Sahu rabu, "Most High God," which Dr. Fr. Delitzsch has so well suggested may be the explanation of the El Shadai, the " Most High God " of the Hebrews. As a ruler and director of all, he was the Potentia of the religio-philosophic triad.

The last member of this triad is one of the most important gods in the whole pantheon. He is called the " Lord of the Earth ;" he was the " Lord of the Sea," the " Lord of the Absu (House of Wisdom)," the " Lord of the Bright Eye (Far-seeing)," the " Lord of the noble Incantation;" but he was chiefly celebrated for his wisdom. In the inscriptions we find him consulted by all the gods in times of trouble, as in the tablet of the War against the Moon (W. A. I. iv., 5, 37, 54) we read that when the god Bel saw the trouble afflicting the Moon, he called to his messenger, Nusku, the god of " the morning star." —

" Bel to his messenger, Nusku, spoke : '

My messenger, this message to the Absi (House of Wisdom) take — The message that the Moon God in Heaven fearfully is troubled, to Hea in the Absi tell. Nusku the command of his Lord obeyed. To Hea, in the Absi, as a swift messenger, he hastened. To Hea the Master, the Supreme Ruler, the Unchangeable Lord, Nusku, he command of his Lord told.' "

The Deluge tablet brings out more emphatically his character for wisdom. After the cataclysm we read Bel was angry that some had escaped the Deluge by means of the ark, and asks of his companion-god, Adar, who taught men to build the ark ? upon which the reply is —

" Who, except Hea, can form a design ? Yea, Hea knows all things, and he teaches (them)."

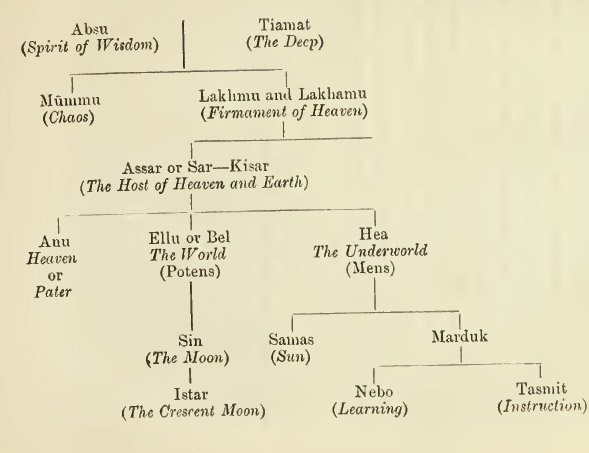

We see, therefore, that as " the god of metals, the god of the rivers and streams," he is Pluto and Cronos of the mythological triad, and the Mens of the philosophical. From this small fragment we get the following table of the Birth of the Gods : —

The examination of this fragment shows that it presents a close and remarkable agreement in many points with both the Phoenician and Hebrew theogonic legends. With regard to the latter we may say that its parallelisms are to be found in the creations of the first two days (Gen. i. 1-9).

We now pass to the other tablets of the series. There is no tablet corresponding to the work of the third day (Gen. i. 9-13) ; but the fifth tablet of the series, which corresponds to the work of the fourth day in the Hebrew account (Gen. i. 14-23), is very fortunately the best preserved of the series. The careful way in which this tablet was drawn up, and its detailed analysis of the arrangement of the heavenly bodies, throws very great light upon the date and character of these tablets. The text of the tablet, which is published, Delitzscli-Assyriologische Lesestucke, pi. 70, is well preserved in the obverse, though the reverse is unfortunately lost.

Fifth Tablet:

- He made pleasant the dwelling places of the great gods.

- The constellations their forms as animals he fixed.

- The year its divisions he divided.

- Twelve months of constellations by threes He fixed,

- From the day when the year began to its end.

- He determined the place of the crossing stars, and the seasons their bound* ;

- Not to make fault or error of any kind.

- The positions of Bel and Hea, he established with his own.

- He opened great gates in the side of the world :

- The bolts he made strong on the left hand and the right.

- In the mass he made an ascent.

- The Illuminator (Moon-god) he made to shine, to rule the night.

- He appointed it also to establish the night until the coming forth of day.

- Every month, without fail, by its disk he regulated.

- In the beginning of the month, at the rising of the night

- Horns shine forth to lighten the heavens.

- On the Seventh day a circle it approaches.

- To divide the dawns, he appointed (it — '?)

- When the Sun on the horizon of heaven at Thy coming.

At the first inspection of this tablet it is evident that we have before us a document of the highest importance, full of remarkable agreement with the Hebrew tradition, and at the same time presenting us with several striking divergences. With the confused account of the Phoenician priest it presents very little agreement, and the fragment of Berossus in correspondence with it being lost, our comparative studies are confined to the Hebrew record. The opening words of the fourth day in the Mosaic account (Gen. i., 14, 15) present a contrast which perhaps does not appear at first —

"And God said, Let there be lights in the firmament of the heaven, to divide the day from the night, and let them be for signs and for seasons and for days and years."

And then a little further on we read,

" He made two great lights, the greater light to rule the day and the lesser lieht to rule the night: He made the stars also."

Here we have a distinct reversal of the Assyrian order of creation. In the tablet we find the stars created first, and arranged in groups for the measurement of time, and the Moon,, the greater light, for the measurement of the month and the night, and the Sun, the lesser light, for the measurement of the day and the year — a sequence which is an exact reversal of the Hebrew one. It is in these varying arrangements that we get very important matter to enable us to contrast the two accounts, and in some measure to approximate their relative ages. It is clear that the Babylonian or Assyrian tablet exhibits a more than rudimentary knowledge of the science of astronomy, as we have before us in these 15 lines —

- The arrangement of the constellations according to the signs of the zodiac ;

- The marking of the four crossing points on the great circle, the solstices and equinoxes ;

- The Lunar phases. Another important point to be noticed is the prominence given to the moon over the sun, and the particular details as to the calculation of the length of the night.

The preference which is given to the moon over the sun here brings us in contact at once with one of the most interesting sections of the growth of religion, and the changes that a religion passes through as a nation advances from one stage of national life to another. In his very valuable paper on the Astronomy and Astrology of the Babylonians (Trans. Soc. Bib. Arch., vol. iii., p. 207), Professor Sayce thus speaks of the priority of the moon over the sun :

" As befitted a nation of astronomers, the moon was considered prior to the sun, and the originator of civilisation."

It is hardly in this way that we can explain the priority. Turning to the astronomical tablets, we gain a little insight into the reason : we find that the name given to the planets by the Akkadians of Lu-Bat was translated by the Assyrians by Tseni, " sheep," the Hebrew tson (Tran. Soc. Bib. Arch., vol. v., pp. 44 and 375;, and also by bibu, literally " bright eyes," and also ailu or ailvm, " bell-wethers," or leaders of the flock. In like manner we find a star, which I am inclined to regard as the pole-star, called " The Star of the Hock of many sheep of the Spirit of Heaven;" and we meet with the expression, " stars like sheep," in the tablet of the War in Heaven.

Turning now to the Hebrew Scriptures, we lind this pastoral nomenclature employed as indicated by the phrase, "He telleth the number of the stars and giveth them all their names " (Psl. cxlvii. 4), but it never assumes the prominence it does among other nations, especially the Arabs. The description of Arab thought in relation to the bright, starry, and moonlit heaven is so graphic, and so explanatory of the inscriptions, that it must be quoted : —

" With the refreshing dews of evening, not Venus only or the moon, but the whole glory of the starry heavens met the eye and touched the spirit of the Arabs. High above the tents and resting flocks, above the nocturnal raid and waiting ambuscade, and all the doings of men, the stars passed along on their glittering courses. They guided the Arabs on their way through the desert ; certain constellations announced the wished-for rain; others the wild storm, the changes of season, the time for breeding in the flocks. Hence to tribes of the desert especially brilliant stars appeared as living spirits, as rulers over nature and the fortunes of mankind."

An Arab poet (Al ISTabiga, iii, 2) uses the beautiful expression,

" A night so long . . . that I say to myself, ' It has no end, and the Shepherd of the Stars will not come back to day.' "

In the Babylonian astronomical tablets we meet with a similar pastoral tone ; indeed throughout the tablets there are hardly any omens relating to cities. To quote a few examples —

" The star on high rises to clouds, and rain it points ;"

" The star of the eagle is observed, the cattle decrease."

Such an omen as the following (W.A.I., vol. iii., pi. G4) —

" The moon at its appearance with the rising sun is seen: The gods the fields of the land to evil assign : Bel courage to the enemy gives " —

points directly to a tribal raid at a time when the moon rises late in the morning, leaving long dark evenings, under cover of which the Bedouin could advance. In these omens we find similar thoughts to those of the Arabs, and ample evidence that it is to a nomadic people we owe such an arrangement as there is in this tablet. It was not, says Speigel, the sun that first attracted the savage by its sight; it was the night sky with its lights, in contrast to the dark earth. So the moon is a friend to the nomad and shepherd : it gives him bright nights to travel or dark nights for his raids, whereas the sun dries up his water and pasturage. The direct ascendency of the moon is again indicated in a bilingual hymn (Del. Lesestucke, pi. 16), where the goddess Istar, as the morning star, is thus addressed by the worshipper —

" Of thy father, the moon god, and thy brother, the sun,"

making the moon father of the sun. The opening lines of this tablet relate to the arrangement of the stars for the measurement of the year : —

- The constellations their forms as animals he fixed.

- The year its divisions he divided,

- From the da}' when the year commences to its end.

- Twelve months of constellations by threes he fixed.

- He determined the place of the crossing stars, to the seasons their bounds ;

- Not to make fault or error of any kind.

- he abode of Bel and Hea he appointed with his own.

The division of the great circle into twelve divisions, through which the sun passed in his yearly journey, is proved by additional matter in the inscriptions. In a large astronomical tablet relating to the divisions of the year, we read (W.A.I., Vol. iii., pi. 53) —

"Twelve months to each year, 360 (60x6) days in number, are recorded."

Again, a few lines mi, we read —

"The rising and appearance of the moon for the month one watches ; the balancing of the stars and the moon and (their) opposition one watches. For the year its months, for the months their days — the tale is made complete."

Also,

" The twelve months in full, from the beginning to the end, to the measure of days fixed."

In the Deluge tablet, (col. iii. 30, 31) —

" I looked to the regions bounding the sea, to the twelve points no land."

It requires hut a very casual examination of the arrangement of the Akkadian calendar, and the accompanying series of the Twelve Legends of Gizdhubar, to see that the calendar is arranged according to a zodiac of twelve constellations similar to our own. For example, the second month is called the month of the Propitious Bull, corresponding to the sign of Taurus ; the third the month of the Twins, corresponding to Gemini; the eleventh the month of the Curse of Rain, corresponding to the sign of Aquarius.

According to this same tablet (Rev. 8), "the beginning of the year appears to have been fixed by the rising of the star Feu or Dilgan, which was the patron star of Babylon (W.A.I, ii. 47), though it is difficult to identify it with any special star. As we learn from this fifth Creation Tablet, the great circle was divided into four parts of three months each, and the division points were marked by the Nibiru or crossing stars that marked the equinox and solstice points. There are two reasons which lead ine to adopt this rendering. In a tablet giving the names of the star of Merodach, during the twelve months we find that in the month Tasrituv, that is September, he is called Nibiru, and this month marks the period when the sun, at the autumnal equinox, passes from the one half of the year to the other. The second argument is furnished by an unpublished tablet (S. 1907), which gives the seasons of the Babylonian year, and this fragment also explains the division into positions of the three great gods mentioned in line 8 of the tablet.

1st Season lost, but we can see from the fragment that it extended from the 1st day of Adar (Feb.-Mar.) to the 30th day of Airu (Ap.-May), and was the season of rain and sunshine. The latter rain of the Jewish calendar.

2nd Season — " From the 1st day of Sivan (May-June) to the 30th day of Ab (July- Aug.), the sun is in the course of Bel, the season of crops and fruits." This was the wheat harvest and fruit season in Palestine. The feast of first-fruits falling in Sivan.

3rd Season — " From the 1st day of Elul (Aug. -Sept.) to the 30th day of March esvan (Oct. -Nov.), the sun is in the course of Anu, the season of rain and clouds." This was the period of the former or autumnal rains in Palestine.

4th Season — "From the 1st day of Kiselev (Nov. -Dec.) to the 30th day of Sabadhu (Jan. -Feb.), the sun is in the course of Hea, the season of storms." This was the winter season of Palestine.

We may conclude from these passages that either the Nibiru were the equinoxes and solstices, or the constellations marking commencement of each of these four seasons.

The analysis of the opening lines of the fifth tablet shew very clearly that in the Chaldean, as in the Hebrew cosmogony, the stars and lights were created to be for signs and for seasons, and for days and years.

I now pass to the creation of the moon, the greater light according to the Babylonian teaching.

- He opened great gates in the side of the world.

- The bolts he made strong on the left hand and on the right.

- In the mass he made an ascent.

- The Illuminator (the Moon-god) he caused to shine, to rule throughout the night.

- He appointed it also, to establish the night until the coming forth of day.

- Every month, -without fail, by its disk he appointed.

- In the beginning of the month, at the rising of the night,

- Horns shine forth to lighten the heavens.

- On the 7th day to a circle it approaches.

- To divide the dawns he established (it).

- At that time the sun on the horizon of heaven at thy coming.

The conception in these lines that the heavenly bodies made their entrance and exit from the regions below the horizon through great gates is one common to most ancient eastern mythologies. In the Egyptian Ritual of the Dead we have the fifteen great pylons of the land of Karneter guarded by genii, armed with swords, through which the deceased had to pass, and through which Osiris passed daily. The description of these gates is found in ch. cxlvi. of the Ritual, which bears the title of " The beginning of the Gates of Aahlu, or Fields of Peace." A similar idea is found to be held regarding the rising of the sun by the writer of the Book of Enoch. A fuller exposition of the Chaldean idea is contained in a hymn to the rising Sun-god (W.A.I. iv., pi. 20, No. 2) :—

- Oh Sun-god, on the horizon of heaven thou dawnest.

- The bolts of the bright heavens thou openest.

- The folding doors of the heavens thou openest.

- Oh Sun-god, to the countries thy head thou liftest up.

- Oh Sun-god, the glory of the heavens over (all) lands thou spreadest.

According to the Gizdhubar Legends, these great gates by which the sun rose and set were guarded by scorpion men, whose:

" heads reached to the threshold of heaven, and whose footing was in the underworld."

"The Illuminator" is the usual title applied to the Moon-god, and in a long hymn to the moon (W.A.I. , vol. iv., pi. 9) we find the deity addressed as Abu Nannar beluv ilii dhdbu chili Hani —

"Father Illuminator, Lord and Good God ruling the gods."

This name of Nannar no doubt was the origin of the myth of Nannaros related by Ctesias. In the fourth and fifth lines of this section of the tablet—

"The Illuminator he caused to shine, to rule throughout the night. He appointed it also, to establish the night until the coming forth of day " —

is exactly in accordance with the Hebrew idea :

" And God made two great lights — the lesser light to rule the night"

(Gen. i. 16).

The description of the phases of the moon is now given ; and, as we see, it was held important in Ohaldea, as in Palestine and among the Arabs, to watch for the new moon, which marked the beginning of the month. Those who have travelled among these clear-eyed sons of the desert know how much sooner they espy the small thin crescent than we with our dull eyes. A number of reports relating to this watching for the new moon are to be seen among the astronomical tablets in the British Museum (W.A.I., vol. iii. pi. li., Nos. 3, 4, 5 ; pi. liii., No. 3). For example (li. 3) : —

" A watch we observe ; on the 29th day the moon we see. May Nebo and Merodach to the King my Lord draw near. Report of Nabu of Assur."

Another longer report is of interest, as showing the difficulties under which the observations were often conducted (pi. li. No. 6):-

To the King my Lord : Thy servant, Istar-iddina-abla,

One of the chiefs of the Astronomers of Arbela.

May there be peace to the King my Lord.

May Nebo, Merodach, and Istar of Arbela

To the King my Lord approach.

On the 29th day a watch we kept.

The House of Observation was covered with cloud.

The Moon we did not see.

Dated month Sebadh (Jany.-Feb.), 1st day in the Eponym year of Bel-Kliarran-sadua.

The date of this tablet is fixed by the Eponym (.'anon as B.C. 649, contemporary with the reign of Manasseh, King of Judah. These tablets show the importance that the Assyrians attached to the observation of the new moon. We may compare this strict watch with the Hebrew customs :

" In the day of your gladness, and in your appointed seasons, and in the beginnings of your months, ye shall blow with the trumpets over your burnt-offerings"

(Numb. x. 10).

"Blow the trumpet in the new moon"

(Ps. lxxxi. 3).

" New moon and sabbath "

(Isa. i. 13).

A fuller explanation of the lunar phases is to be found in an astronomical tablet (W.A.I, iii., 55, 3) : —

The Moon on its appearance, from the 1st day to the oth day,

For five days is visible. The Moon is Ann.

From the 6th day to the 10th day, for five days it is full. It is Hea.

From the 11th day to the 15th day, for five days to a crown it grows.

The Moon is Anu, Bel and Hea in its mass.

This tablet, we see, also gives the same division of the lunar orbit as that recorded in line 8, and enables us to identify Ann as the creator of the heavenly bodies. In a hymn to the moon, also, we get the following paragraph in praise of the bright " horns " :

" Oh, glowing light ! whose horns are powerful, whose limbs (rays) are perfect, pure as crystal;" and the beauty of its far spreading light is recorded in these words : " Lord, in thy divine form the remote heavens and wide spreading sea thou fillest with thy reverence."

It is extremely unfortunate that the remaining lines relating to the creation of the sun are in so mutilated a condition as to render any connected translation impossible.

The path of the sun is mentioned here by the name of Kliarran Samsi; and the bright god is addressed by the epithet, most frequently applied to him, of the Judge. In the Michaux stones in the Louvre, and in most of the boundary-stone inscriptions, we find this deity, like the Greek Helios, addressed as Dian Nisi —

" Judge of men."

In one example (W.A.I., vol. hi., pi. 42, 19):

"Oh, Sun-god, judge of heaven and earth, his face may he smite, and his bright day to darkness may he turn."

In other inscriptions we find this idea of the sun as the all-seeing judge more strongly expressed, as in the Cylinder of Tiglath-Pileser i. (B.C. 1120) (W.A.I., vol. i., i.-ix. 7), the sun is called

" the patrol surpriser of his enemies, the scatterer of the sheep (stars);"

and in an unpublished hymn to Gizdhubar, the solar hero, we find the phrases —

" Oh Gizdhubar, perfect king, judge of the spirits, exalted prince, lord of mankind, patrol of the four quarters, recorder of the earth, lord of the underworld. Thou art a judge, and decidest like a god ; thou standest upon earth holding judgment — thy judgment is not reversed or thy sentence ignored ; thou rulest, thou examinest, thou judgest, thou decidest and governest. The Sun-god has put the sceptre of decision into thy hand."

This character of the Judge of all is the most important phase of the solar worship of Babylonia, It is referred to in the few mutilated lines of this creation tablet in the words dina dinu —

" Judgment he judges."

The lines already quoted (13) —

"He appointed it (the moon) to establish the night, until the coming forth of day," —

show that in this cosmogony, as in that of the Hebrews, the sun was " to rule the day" (Gen. i. 16).

The next tablet is a small fragrament forming part of the Daily Telegraph collection, which, though very mutilated, evidently corresponds to the work of the sixth day in the Hebrew account (Gen. i. 24, 25), the creation of the cattle and creeping things : —

- When the gods in their assembly had made,

- They made all things pleasant.

- They caused to come forth living creatures.

- The cattle of the field, the beasts of the field, and the creeping things.

- . . . . . to living creatures

- The cattle and creeping things of the city they sent forth.

- The assembly of creeping things and all creation,

- . . . which in the assembly of my family.

- the God of the Holy Eye (Hea), pairs associated.

- . . . The assembly of creeping things he scattered abroad.

Fragmentary and mutilated as this tablet is, it contains much of importance, and, like the fifth tablet, affords some indication of the character of the people who composed the cosmogony. The expression " living creatures," sihiat napiste, is a near equivalent of the Hebrew nephesh-khay-yah in Gen. i. 24, and is used through the Assyrian sacred literature for the expression of animated nature. Like the fifth tablet, this one was drawn up with great care. We see the domestic cattle (bulu) distinguished from the wild animals (umami) of the field, and the latter are omitted when the animals of the city are spoken of. The fuller sense of this idea of the wild beast as distinct from domestic cattle is shown in the obelisk inscription of Tiglath-Pileser, i. (b.c. 1120) (W.A.I, i., pi. 28), where we read,

" the rest of the numerous animals (umami), the winged birds of the air, which, among the beasts of the field, the work of his hands.'"

In this same text the expression is umami sa tehamte, " beasts of the sea," is used to express some of the marine monsters captured by the king during his expedition to the shores of the Mediterranean ; so that this text, although not one of the creation series, serves to connect the fifth tablet and our fragment, and to indicate the existence of a similar account of the fifth day's creation as that found in the Hebrew version (Gen. i. 20-23).

The distinction in the tablet between the cattle of the field or desert and those of the city, the priority being given to the former, bears out what I have already spoken of regarding the origin of the legends being sought among the nomadic Semites rather than the citydwelling Akkadians. It is most probable that had we the remainder of this tablet we should have found in it the Assyrian story of the creation of mankind. The deity mentioned here under the title Nin-EniIllute, " Lord of the bright eye," is the god Hea, and it is to this " all- wise " god that the creation of mankind is attributed.

In the tablet which Mr Smith regarded as the Chaldean account of the fall, but which Dr. Oppert has conclusively shown is a hymn to the god Hea, we find the words, " Ana Padi sunu ilmu avilute" " to be obedient to them (the gods) he made mankind;" also, we read, likuna aima aniatu su ina pi zalmat hakkadi sa ibna kata su, " May his command be established in the mouth of mankind, who his 1 lands have made."

In the hymns we often iind that Merodach, the son of Hea, who occupies a position but a slight degree inferior to that of his father, often assumes the divine titles and prerogatives of his father, as in the following passage from a hymn : —

" The incantation of life is thine, the Philtre of life is thine, the Holy writing of the House of Wisdom (Absu) is thine;"

and then the following important passage : —

Avilutuv zalmat kakkadi, siknat napisti mala suma naba ina mate basa, —

"Mankind, (even) the human race, the living creatures, all that by name is called (and) in the land exists is (thine).

The four quarters (are thine). The angel host of heaven and earth, all that exist (are thine)"(W.A.T., vol. iv., pi. xxix., No. 1, 30-44).

It would appear, therefore, to Hea, or to his son Merodach, or to the pair conjointly, that we must attribute the creation of the human race, and if this is the case, it tends to support very strongly the proposition of Sir Henry Rawlinson that Hea was the god of the section of the Akkadians who in their religious development attained nearest to Monotheism. I need hardly, now that we have reached the end of our examination of these tablets, show how striking in thought and expression, often in identical language, is the resemblance between the Assyrian and the Hebrew accounts. Even that oft repeated refrain of divine satisfaction' and " God saw that it was good," finds its counterpart in the phrase occurring in both tablets five and seven, — " Ubassim," " He made pleasant." There now remains the very important, but equally difficult, question of the date and relationship of these tablets to the Hebrew account. And here I must ask my readers to bear in mind the fact that I am treating this subject from a purely Assyriological side, leaving the Hebrew side to those more competent to deal with it than myself.

The first point to be noticed is the marked difference between the Creation Tablets and the generality of Assyrian tablets. The majority of the religious tablets, litanies, hymns, prayers, etc., found in the Assyrian royal library at Nineveh, are admittedly copies from older documents in the temple libraries of Chaldea, and> each bears a colophon or docket on the reverse, stating it to be Kima labri sit, "like its old copy." We find the docket upon all the tablets of the Gizdhubar Legends, including the Deluge Tablet'; upon the Dibbara Legends, and upon the bilingual Akkadian and Assyrian hymns, etc. There are, however, a certain class of tablets which do not bear this statement, such as the very beautiful series of Assyrian prayers (W. A. I., vol. iv., pi. 58, 59, 6^!, 04), and examination of these tablets shows them to be distinctly Semitic in character, thought, similies, and language.

They may be here and there inilnenced by Akkadianisms, but they are essentially different from the magical hymns and formulae. In like manner we find the Creation Tablets omit this colophon. This would seem at first to mark them of a date as late as B.C. 650, the time when the library at Nineveh was founded by Assurbanipal. This cannot be admitted in the face of further evidence from beneath the dust of ages. Among the fragments of tablets obtained by Mr Eassam and others from the excavations in the Birs Nimroud, the site of the ancient temple of Nebo, the god of learning, are some duplicate copies of the Creation Tablets, portions of the fifth, and also a large tablet of the series relating to the War in Heaven. At the same time duplicates of other texts, grammatical tablets, and the Deluge Tablet, in the library of Nineveh, have been obtained from the excavations at Birs Nimroud and Aboo Hubba.

The character of the writing and the arrangement of the texts, as well as the historical impossibility — the library at Nineveh probably being in ruins at the time when the tablets were written, in the reigns of Nebuchadnezzar and Nabonidus (b.c. 604-555) — would militate seriously against the Babylonian version being copied from the Assyrian. We must therefore conclude that copies were in the Babylonian libraries prior to B.C. GGO, and it was from these that the later copies, as well possibly as the Assyrian versions, were made. The advanced knowledge of astronomy exhibited in the fifth tablet brings us in close contact with the astronomical tablets. It is evident from the definite and accurate description of the comet of about the year 1120 B.C. given in the tablets (W. A. I., iii., 52, 1) that as early as the 12th century Baylonian astronomy was in a very high state of development.

The writers of the tablets attribute the compilation of the important series of astronomical tablets entitled " The Book of the Illumination of Bel," to Sargon of Akkad, whose date is now fixed as B.C. 3750. This may be only a mythical story ; but if the tablet of the Wars of Sargon and Naram-Sin (W. A. I, vol. iv., pi. 34) is, as it appears to be, a genuine copy of a Babylonian document, there is more proof of its truth than at first appears.

By the arrangement of the Gizdhubar legends according to the signs of the Zodiac, and the Equinoxial Festivals in the Sacrificial Tablet from Aboo Hubba, it appears that the seasons, the equinoxes, etc., had been observed and used as time measurers as early as b.c. 2400. I have already pointed out that the prominence given to the moon and stars in the fifth, and the distinction made in the seventh between the animals of the plain and town, marks the influence of the nomadic life upon the thoughts of the compilers of these tablets.

We may now turn to a very remarkable series of tablets dating in the reign of Khammurabi, whose date Mr Pinches has established as B.C. 2120. In these tablets we get a series of proper names of a remarkable character, such as Abil, Kainuv, Ismi-ilu, which resemble the Hebrew Abel, Cain, and Ishmael ; but also we have such names as Ilu bani, " God has made," Ana-pani-ilu, " To the face of God," Ilu iddina, " God has given," while many hundreds of names occur in which the name of the Moon-god is the most prominent element. The evidence to be deduced from these tablets is, that as early as the twenty-second century before the Christian era there were living in the neighbourhood of Ur and Larsa the Ellassar of Gen. xiv., 1. — a population speaking a language akin to that of the Hebrews, worshipping an abstract deity, the Ilu El of the Hebrews, the Allah of the Arabs, and in their pantheon placing the Moon-god in the foremost place. May not these ancestors, and pos- sibly companions, of Abraham, have known at least the elements of these traditions of the Beginnings of all things ?

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

From which the word Kitsrituv, " harvest," is derived.