Babylonian Religion and Mythology

by Leonard William King | 1903 | 52,755 words

An account of the principal facts concerning Babylonian religion and mythology. This account is based upon the cuneiform inscriptions which have been excavated in Mesopotamia during the last fifty-five years....

Chapter II - Heaven, Earth, And Hell

The conception formed by the Babylonians with regard to the shape and nature of the earth on which they lived, and the ideas they held respecting the structure of the heavens, and the expectation which they entertained of one day dwelling in some region beyond the grave, can only be gathered from various stray references and allusions scattered throughout the remains of their literature. We possess no treatise on these subjects from the pen of a Babylonian priest, and we have to trace for ourselves and piece together the beliefs of the Babylonians on all these questions from passages in their historical and religious writings.

That the ancient Babylonians concerned themselves with such problems there is ample evidence to show, and, although they have left behind them no detailed description of the universe, it is possible by a careful study of the texts to obtain a fairly complete idea of the world as they pictured it. To understand many of the legends and stories told concerning the Babylonian gods and heroes it is necessary to consider heaven, earth, and hell from their standpoint; it will be well, therefore, to trace their views concerning these regions before passing to the myths and legends that are translated or referred to in the following chapters.

Shape of the Earth.

With regard to the formation and shape of the earth we find a very interesting passage in a legend told concerning the old Babylonian hero Etana. The Eagle was a friend of Etana, and on one occasion this bird offered to carry him up to heaven. Etana accepted the Eagle’s offer, and, clinging with his hands to the Eagle’s pinions, he was carried up from the earth. As they rose together into the higher regions, the Eagle told Etana to look at the earth which grew smaller and smaller as they ascended; three times at different points of his flight, he told him to look down, and each time the Eagle spoke he compared the earth to some fresh object.

After an interval of two hours the Eagle said,

“Look, my friend, at the appearance of the earth. Behold, the sea, at its side is the House of Wisdom.[1] Look how the earth resembles a mountain, the sea has turned into [a pool of] water.”

After carrying Etana up for two more hours the Eagle said,

“Look, my friend, at the appearance of the earth. The sea is a girdle round the earth.”

After ascending for a further space of two hours the Eagle exclaimed,

“The sea has changed into a, gardener’s channel”;

and at a still higher point of their flight the earth had shrunk to the size of a flower-bed. From these passages we see that the writer of the legend imagined the earth to be like a mountain around which flowed the sea. At the first stopping place Etana and the Eagle were so high that the sea looked like a pool of water, in the middle of which the earth rose. Later the sea had become so small that it looked like a girdle round the earth, and at length it appeared very-little larger than a “gardener’s water-chaunel” made for irrigation purposes.

Position of the Sea.

The belief that the earth was hemispherical in shape, resembling a mountain with gently sloping sides, was common among the Babylonians as we know from other passages. According to Diodorus Siculus[2], the Babylonians said that the earth was “like a boat and “ hollow.”[3] The boat used on the Tigris and Euphrates, and representations of which frequently occur on the monuments, had no keel and was circular in shape.[4] Such a boat turned upside down would give a very accurate picture of the Babylonian notion of the shape of the earth, the base of which the sea encircled as a girdle encircles a man. To a dweller on the plains of Mesopotamia the earth might well seem to be a mountain the centre of which was formed by the high mountain ranges of Kurdistan; while the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean which were on the south-east of Babylonia, and the Bed Sea and the Mediterranean lying to the south-west and west respectively, doubtless led to the belief that the ocean surrounded the world.

The Dome of Heaven.

At some distance above the earth was stretched out the heaven, a solid dome or covering in the form of a hollow hemisphere, very much like the earth in shape. Both earth and heaven rested upon a great body of water called Apsū, i.e., the Deep. It is not quite certain how the solid dome of heaven was supported, that is to say, it is not clear whether it was supported by the earth, or was held up, independently of the earth, by the waters. According to one view the edge of the earth was turned up and formed around it a solid wall like a steep range of hills upon which the dome of heaven rested; and in the hollow between the mountain of the earth and this outer wall of hills the sea collected in the form of a narrow stream.

This conception coincides with some of the phrases in the legend of Etana, but against it may be urged the fact that the sea is frequently identified with Apsū or the primeval Deep upon which the earth rested. But if the edges of the earth supported, the dome of heaven, all communication between the sea and Apsū would be cut off. It is more probable therefore that the earth did not support the heaven, and that the foundations of the heavens, like those of the earth, rested on Apsū. In the (beginning, before the creation of the world, nothing existed except the water wherein dwelt monsters. According to a version of the creation story, however, the god Bēl or Marduk formed the heavens and the earth out of the body of a great female monster that dwelt in the Deep which he had slain. Splitting her body into two halves, he fashioned from one half the dome of heaven, and from the other the earth.[5]

The Heavenly Bodies.

Above the dome of heaven was another mass of water, a heavenly ocean, which the solid dome of heaven supported and kept in its place, so that it might not break through and flood the earth. On the under side of the dome the stars had their courses and the Moon-god his path.

The Path of the Sun-God.

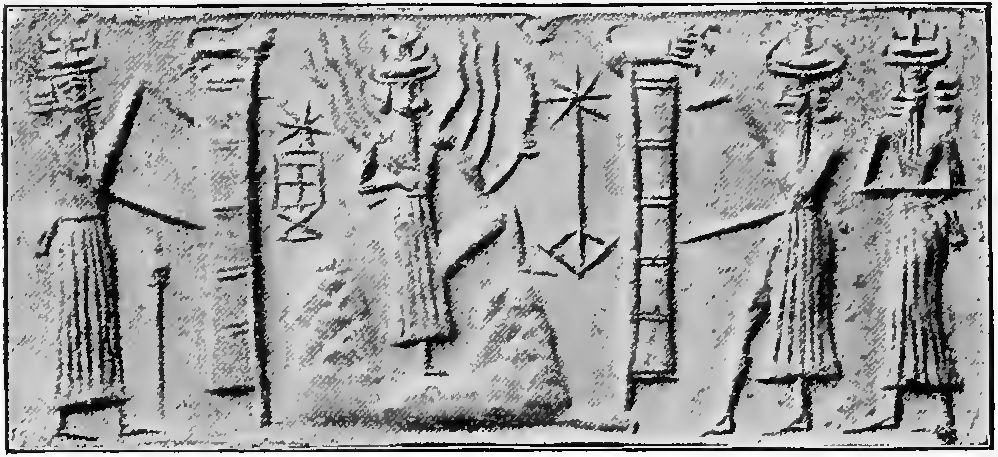

In the dome, moreover, were two gates, one in the east and the other in the west, for the use of Shamash, the Sun-god, who every day journeyed from one to the other across the world. Coming from behind the dome of heaven, he passed through the eastern gate, and, stepping out upon the Mountain of the Sunrise at the edge of the world, he began his journey across the sky. In the evening he came to the Mountain of the Sunset, and, stepping upon it, he passed through the western gate of heaven and disappeared from the sight of men. According to one tradition he made his daily journey across the sky in a chariot, which was drawn by two fiery horses. In representations on cylinder-seals, however, he is generally shown making his journey on foot. In the accompanying illustration Shamash is seen appearing above the horizon of the world, as he enters the sky through the eastern gate of heaven.

Image: Shamash, the Sun-god, coming forth through the eastern door of heaven. (Prom a cylinder-seal in the British Museum, No. 89,110.)

The Gates of Heaven.

In the following hymn, addressed to the Rising Sun, a reference is made to Shamash entering the world through the eastern gate of heaven:—

“O Shamash, on the foundation of heaven thou hast flamed forth.

Thou hast unbarred the bright heavens,

Thou hast opened the portals of the sky.

O Shamash, thou hast raised thy head over the land.

O Shamash, thou hast covered the lands with the brightness of heaven.”

Another hymn, addressed to the Setting Sun, contains a reference to the return of Shamash into the interior of heaven :—

“O Shamash, when thou enterest into the midst of heaven,

The gate-bolt of the bright heavens shall give thee greeting,

The doors of heaven shall bless thee.

The righteousness of thy beloved servant shall direct thee.

Thy sovereignty shall be glorious in E-babbara, the seat of thy power,

And Ai, thy beloved wife, shall come joyfully into thy presence,

And she shall give rest unto thy heart.

A feast for thy godhead shall be spread for thee.

O valiant hero, Shamash, [mankind] shall glorify thee.

O lord of E-babbara, the course of thy path shall be straight.

Go forward on the road which is a sure foundation for thee.

O Shamash, thou art the judge of the world, thou directest the decisions thereof.”

The Innermost Part of Heaven.

Each evening when Shamash entered the innermost part of heaven he was met by Ai, his wife, and he feasted and rested from his exertions in the abode of the gods. For, beyond the sky which was visible to men, and beyond the heavenly ocean which the dome of the sky supported, was a mysterious realm of transcendental splendour and beauty, the Kirib Shamē, or “Innermost part of Heaven,” where the great gods at times dwelt apart from mankind. As a general rule the greater number of the gods dwelt upon earth, each in his own city and shrine, and each was believed to be intent upon the welfare of his worshippers; but at any moment they could, if they so desired, go up to heaven.

Thus, the goddess Ishtar was wont to dwell in the ancient city of Erech, but when she thought that an insult had been offered to her divinity by the hero Gilgamesh she at once ascended into heaven and demanded vengeance from her father and mother, that is to say, Anu the god of heaven, and Anatu his wife.[6] Again, the deluge sent by Bēl upon the earth, besides destroying mankind, overwhelmed the shrines and temples of the gods who dwelt in the land, and they were driven forth and fled in fear to heaven, the realm of Anu.[7] It was, however, only upon rare occasions that the gods left the earth, and it is in accordance with this rule that the council-chamber of the gods, where fate and destiny were decreed, was not in heaven but upon the earth. The name of this chamber was Upshukkinaku, and here the gods gathered together when they were summoned to a general council. This chamber was supposed to be situated in the east, in the Mountain of the Sunrise, not far from the edge of the world where it was bounded by the waters of the great Deep.

The House of the Dead.

It has already been stated that the earth was thought by the Babylonians to be in the form of a great hemisphere, and we must now add that they believed its hollow interior to be filled with the waters of the Deep upon which it also rested. The layer of earth was not, however, regarded as a thin crust. On the contrary, though hollow, the crust of solid ground was throught to be of great thickness. Within this crust, which formed the “mountain of the world,” deep down below the surface of the ground, was a great cavern called Arallū, and here was the abode of the dead. In this region was the great House of the Dead which was surrounded by seven walls; these were so strongly built, and so carefully watched and guarded by beings of the underworld, that no one who had once entered therein could ever hope to return again to earth; indeed another name for Arallū, or the underworld, was māt lā tāri, “The land of no return.” The House of the Dead was dark and gloomy, and in it the dead dragged out a weary and miserable existence. They never beheld the light of the sun, but sat in unchanging gloom. In appearance they resembled birds, for they were clothed in garments of feathers; their only food was dust and mud, and over everything thick dust was scattered.

The Joyless Existence of the Dead.

The Babylonians had no hope of a joyous life beyond the grave, and they did not conceive a paradise in which the deceased would live a life similar to that he lived upon earth. They made no distinction between the just and the unjust, and the good and the bad, but believed that all would share a common fate and would be reduced to the same level after death. The Babylonians shared this conception of the joyless condition of the dead with the Hebrews, by whom Sheōl, or Hell, was thought to be a place where the dead led an existence deprived of all the joys of life.

In Isaiah the dead, including “the chief ones of the earth” and “the kings of the “ nations,” are pictured as trooping forth to meet the king of Babylon when he joins their company; and they answer and say unto him:

“Art thou also become weak as we ? Art thou become like unto us ? Thy pomp is brought down to hell and the noise of thy viols: the worm is spread under thee and worms cover thee.”[8]

Ezekiel also emphasizes the same contrast between the condition of the living and the dead. Those that have caused terror in the land of the living, when they are slain lie still, and

“bear their shame with those that go down to the pit.”[9]

The Psalmist prays to Jehovah for deliverance,

“for in death there is no remembrance of thee: in Sheol who shall give thee thanks ?”[10]

The Gods of the Dead.

The goddess who presided over this joyless realm of the dead was named Allatu, or Ereshkigal, and ahe was associated in her rule with the god Nergal in his character as the god of the dead. The name of the wife of Nergal was the goddess Laz, but legend tells how Nergal forced his way into the Lower World with the purpose of slaying Allatu, and how the goddess by her entreaties prevailed on him to spare her life and marry her. Henceforth Nergal and Allatu ruled together over the realm of the dead. The chief minister of Allatu was Namtar, the demon of pestilence and disease, who acted as her messenger and put her orders into execution. Allatu’s decrees were written down by a goddess called Bēlit-tsēri, “the “Lady of the Desert,” who possibly took her name from the wild and barren desert that shut in Babylonia on the west; and the chief porter who guarded its entrance was a god named Nedu. The Anunnaki, or “Spirit of the Earth,” also frequently acted under the orders of Nergal and Allatu. In addition to these chief deities Allatu exercised control over a number of demons, who, like Namtar, spread plague and disease among mankind, and so brought fresh subjects to the realm of their mistress.

A Babylonian Grave-Tablet.

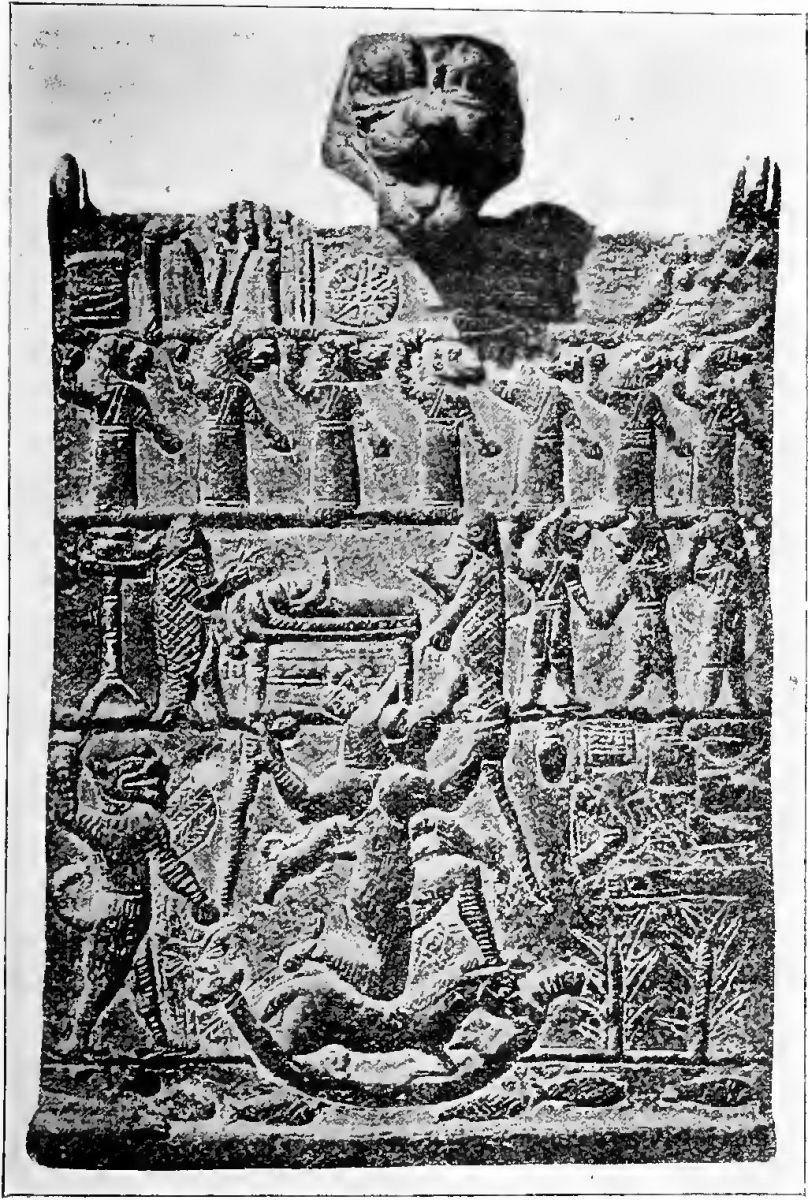

Image right: Bronze plate on which are depicted the gods of the dead in attendance upon a deceased person and certain demons and dwellers in the underworld. (From Revue Archéologique, Nouv. Sér., Vol. 37.)

Image right: Bronze plate on which are depicted the gods of the dead in attendance upon a deceased person and certain demons and dwellers in the underworld. (From Revue Archéologique, Nouv. Sér., Vol. 37.)

The form and appearance of certain of the gods and demons of the underworld may be gathered from a number of engraved bronze plates which have come down to us; these, it has been suggested, were intended to be placed as votive tablets in the graves of the dead. The accompanying illustration has been taken from the finest known specimen of this class of object which was purchased in Syria some twenty years ago; it had evidently been brought there from some ancient Babylonian city. On the back of this tablet is cut in relief the figure of a mythical winged beast with a lion’s head; it stands on its hind legs and raises its head above the edge of the plate, the top of which it grasps with its fore-paws. On the front of the tablet, which is here reproduced, a funereal scene is represented. The beast looking over the top of the tablet is identified by some with the god Nergal, who was believed to preside over the funeral rites which are being performed for the deceased.

It will be observed that the scene is divided by means of thick lines into four registers. The first register contains the emblems of a number of the gods. Here we have a group of seven small circles or stars, and a crescent, and a winged solar disk, and a circle containing an eight-rayed star, and a cylindrical, horned head-dress, and other objects. It has been suggested that these emblems had astrological significance,[11] and if this be the case they may perhaps represent a particular grouping of the stars of the heavens and so indicate the date of the death of the man for whose benefit the tablet was made. The occurrence of such emblems, however, is frequent, both on royal monuments (e.g., the stele of Ashur-nātsir-pal, and the stele of Shalmaneser II., and the rock inscription at Bavian), and on inscribed cylinder seals; and on these two classes of objects the emblems do not appear to have any astrological significance. It therefore seems more correct to explain their position at the head of the tablet by assuming that they are placed there as amulets to secure for the dead man the favour of the deities whose emblems they were.

A Funeral Scene.

The next three registers into which the rest of the scene is divided have been supposed to represent different stages in the upper and lower world. It is preferable, however, to suppose that the three groups of figures in the three registers are parts of one scene, though they are placed, as is frequently the case in archaic sculptures, one above the other. The whole scene represents the deceased lying on his bier, attended by demons and beings from the underworld. In the second register we have seven mythical creatures with the bodies of men and the heads of beasts. They all are clothed in long tunics which teach to the feet, and they all face towards the right, and the right hand of each is raised. Each being has the head of a different beast. Beginning on the right it will be seen that the first one has the head of a serpent, the second that of a bird, the third that of a horse, the fourth that of a ram, the fifth that of a bear, the sixth that of a hound, and the seventh that of a lion.

Certain other gods or demons occur in the third register. The first one on the right, who is in the form of a bearded man, has his right hand raised in the same manner as the seven beings in the second register, and next to him stand two lion-headed creatures, clasping hands. All these gods or demons appear to belong to the region of the dead, and they seem to be guarding the bier of the deceased, who is lying upon it with hands clasped and raised above him. On the left is the deceased in his grave-clothes; at his head and feet stand two attendants, with their right hands raised, and they appear to be performing some mystic ceremony over the corpse. The dress of these attendants is remarkable, for they wear garments made in the form of a fish. Behind the attendant at the head of the bier is a stand for burning incense.

Guardians of the Dead.

The most interesting figures on the plate are those in the fourth register, for they represent two of the chief deities of the underworld. The female figure in the centre is the goddess Allatu, the queen of the dead. She has the head of a lioness and the body of a woman; in each hand she grasps a serpent, and a lion hangs from each breast. She kneels upon a horse in a boat and is sailing over the “Waters of Death,” which adjoin Apsū, the primeval ocean that rolls beneath the earth. The hideous, winged demon behind her is Namtar, the demon of the plague, who waits upon her and is ever ready to do her bidding. It is not certain what the objects in front of Allatu are, but it is probable that they are intended to represent the offerings which were placed in the grave with the deceased. The purpose of the tablet seems to have been to secure the safe passage of the dead man into Arallū, or the underworld.

Other Grave-Tablets.

A somewhat similar bronze tablet, but less well preserved, is in the Imperial Ottoman Museum at Constantinople, and is said to have been found at Surghūl in Southern Babylonia.[12] On the back of this tablet, beneath the feet of the monster who looks over tbe top, a space of four lines has been left blank to receive an inscription which would either record the name and titles of the deceased, or contain an incantation which was to be recited for his benefit. On the back of a similar, though somewhat smaller tablet that was evidently intended to be used for the same purpose (although it only represented the goddess Allatu, while the bier and the Plague-demon Namtar and the other gods or demons found on the larger tablets were wanting), a longer inscription was found. This tablet was published by Lajard, but the text is so badly copied that it cannot be read with certainty.[13] A still smaller tablet of the same character is preserved in the British Museum.[14]

Perhaps in no matter do the Babylonians afford a more striking contrast to the Egyptians than in the treatment of the dead. In the moist, alluvial soil of Mesopotamia the dead body fell quickly into decay, and in the absence of ranges of hills such as those which run on each side of the Nile Valley, the making of rock-hewn tombs in which the bodies of the dead might be preserved was impossible. It is to this fact, probably, that we may trace the ideas of the gloomy existence which the Babylonians believed they would lead when they passed beyond the grave. It must not be imagined, however, that the Babylonians attached no importance to the rites of burial.

On the contrary, the greatest misfortune that could befall a man was to be deprived of burial, for, in this case, it was thought that his shade could not reach Arallū, and that it would have to wander disconsolately about the earth, where, driven by the pangs of hunger, it would be obliged to eat and drink any offal or leavings which it might find in the street. It was in order to ensure such a fate to his foes that Ashur-bāni-pal, on his conquest of Susa, caused the graves of the kings who had been dead and buried many years to be disturbed and their bones to be dragged to Assyria; and the same object prompted the mutilation of corpses on the battlefield and the casting forth of the dead bodies to be devoured by birds and beasts of prey.

Wandering Shades.

To leave a body unburied, however, was not unattended with danger to the living, for the shade of the dead man, during its wanderings over the earth, might bewitch any person it met and cause him grievous sickness. The wandering shade of a man was called “ekimmu,” i.e., spectre, and the sorcerer and the witch claimed to possess the power of casting a spell whereby an “ekimmu” might be made to harass a man. On the other hand an “ekimmu” would sometimes settle on a man of its own accord, in the hope that its victim would give it burial in order to free himself from its clutches.

We have in the British Museum an interesting incantation which was intended to be recited by a man on whom an “ekimmu” had fastened itself,[15] and from this we learn that a man, who had fallen sick in consequence, might cry aloud in his pain, saying:—

“O Ea, O Shamash, O Marduk, deliver me,

And through your mercy let me have relief.

O Shamash, a horrible spectre for many days

Hath fastened itself on my back, and will not loose its hold upon me.

The whole day long he persecuteth me, and in the night season he striketh terror into me.

He sendeth forth pollution, he maketh the hair of my head to stand up,

He taketh the power from my body, he maketh mine eyes to start out,

He plagueth my back, be poisoneth my flesh,

He plagueth my whole body.”

The sick man in his despair prays to Shamash to be delivered from the ekimmu, whoever he may be, saying

“Whether it be the spectre of one of- my own family and kindred,

Or the spectre of one who was murdered,

Or whether it be the spectre of any other man that haunteth me.”

In order to ensure the departure of the spectre to the underworld he next makes the necessary offerings which will cause the spirit of the unburied man to depart, and says:—

“A garment to clothe him, and shoes for his feet,

And a girdle for his loins, and a skin of water for him to drink,

And ...[16] as food for his journey have I given him.

Let him depart into the West,

To Nedu, the chief Porter of the Underworld, I consign him.

Let Nedu, the chief Porter of the Underworld, guard him securely,

And may bolt and bar stand firm (over him).”

Laying a troubled Spirit.

It is clear, therefore, that in their own interest, as well as in that of the deceased, a man’s friends and relations took good care that he was buried with all due respect, and ensured his safe journey to the lower world by placing in the grave offerings of meat and drink to sustain him by the way; such offerings were perhaps also intended to alleviate his unhappy lot after his arrival in the gloomy abode of the underworld. Not many details have come down to us with regard to the ceremonies that were performed at the grave, but we know that after a man’s death his house was filled with mourners, both male and female, whom his family hired in order that they might give public expression to the grief occasioned by his death.

Mourning for the Dead.

Among the Assyrian letter-tablets in the British Museum there is one[17] which refers to the death of the reigning king and to the regulations for mourning that were to be observed at the court.

“The king,” the letter says,

“is dead, and the inhabitants of the city of Ashur “weep.”

The writer of the letter then goes on to describe the departure of the governor of the city with his wife from the palace, the offering up of a sacrifice, and the wearing of mourning raiment by the whole court; and it finally states that arrangements had been made with a director of music to come with his female musicians and sing dirges in the presence of the court. The mourning on the death of a private citizen would of course be carried out on a more modest scale.

Burial Rites.

After the mourning for the dead man had been performed, his body, duly prepared for burial, was carried forth to the grave. That the burial of the dead with accompanying rites and offerings was practised in Babylonia from a remote period is proved by a representation on a stele which was set up to record the victories of Eannadu, an ancient king of the city of Shirpurla, who reigned in all probability before B.C. 4000. On a portion of this stele is a representation of the burial of those of his warriors who had fallen in battle. The dead are laid in rows, with head to feet alternately, and above them a mound of earth has been raised; their comrades are represented bearing baskets containing more earth for the mound, or perhaps funeral offerings for the dead.[18]

The Interment of a King.

On the monuments of later Babylonian and Assyrian kings we do not find any representation of burial ceremonies, but in a broken inscription of one of the later Assyrian kings, whose name has unfortunately not been preserved, we have a brief but very interesting account of the ceremonies which he performed at his father’s burial.[19]

He says—

“Within the grave,

The secret place,

In kingly oil,

I gently laid him.

The grave-stone

Marketh his resting-place.

With mighty bronze

I sealed its entrance,

I protected it with an incantation.

Vessels of gold and silver,

Such as (my father) loved,

All the furniture that befitteth the grave,

The due right of his sovereignty,

I displayed before the Sun-god,

And beside the father who begat me,

I set them in the grave.

Gifts unto the princes,

Unto the Spirits of the Earth,[20]

And unto the gods who inhabit the grave,

I then presented.”

From this we learn that the king placed vessels of gold and silver in the grave as dedicatory offerings, and after sealing up the entrance to the grave he pronounced a powerful spell to prevent the violation of the tomb by robbers; he also presented offerings to propitiate the demons and dwellers in the underworld.

Preservation of the Dead Body.

Another interesting point about this record is the fact that the dead body is said to have been set “in “kingly oil,” for the oil was clearly used with the idea of preserving the body from decay. Salt also seems to have been used for the purpose of preserving the dead, for Ashur-bāni-pal tells how, when 1STabū-bēl-shumāti had caused himself to be slain by his attendant to prevent himself falling alive into the hands of Ashur-bāni-pal, Ummanaldas had the body placed in salt and conveyed to Assyria into the presence of the king.[21] Besides salt and oil, honey seems also to have been used by the Babylonians for preserving the dead. Herodotus says that the Babylonians buried in honey,[22] and that honey possesses great powers of preserving the dead is proved by the fact that the Egyptians also used it for this purpose.[23] Moreover, it is recorded that Alexander the Great when on his death-bed commanded that he should be buried in honey, and it seems that his orders were obeyed.[24] Tradition also says that one Marcellus having prepared the body of Saint Peter for burial by means of large quantities of myrrh, spices, etc., laid it in a “long chest” filled with honey.[25]

Babylonian Graves.

There is ample evidence, therefore, to show that the Babylonians cared for their dead and took pains about their burial, and it is the more surprising on that account, that during the numerous excavations which have been carried out in Mesopotamia, comparatively few graves have been discovered. Of the graves that have been found, some are built of bricks and are in the form of small vaulted chambers, while others have a flat or domed roof supported by a brick substructure; in addition to these graves a few clay sarcophagi and burial jars have been found. With the skeletons in the graves are usually found a small number of vases and perhaps some simple objects of the toilet; but from the fact that no inscriptions have been found either over these graves or upon any of the objects found therein, it is extremely difficult to assign to them even an approximate date; in fact, some have unhesitatingly assigned them to a period which is much later than that of the ancient Babylonian and Assyrian empires.

To account for this dearth of graves the suggestion has been made that the Babylonians burnt their dead, but not a single passage has been found in the cuneiform inscriptions in support of this view. It is true that in the winter of 1886 and in the spring of the following year the Eoyal Prussian Museum sent out an expedition to Babylonia, which, after excavating the mounds of Surghūl and El-Hibbah, thought they had obtained conclusive evidence that the Babylonians burnt their dead.[26] But it has since been pointed out that the tombs they excavated belong to a period subsequent to the fall of the Babylonian Empire, while the half-burned appearance of the charred human remains they discovered seemed to suggest that the bodies were not cremated but were accidentally destroyed by fire. However the comparatively small number of graves that have been found may be accounted for, we may confidently believe that the Babylonians and Assyrians were in the habit of burying, and not burning, their dead throughout the whole course of their history.

Care for the Dead.

We are right also in saying that they imagined that burial, and offerings made at the tomb, would ameliorate the lot of the departed, and that they were usually scrupulous in performing all rites which could possibly benefit the dead.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

I.e., the dwelling-place of Ea, the Loid of Wisdom, who dwelt in the deep.

[2]:

A Greek historian, born in Sicily, who lived in the first century before Christ, and wrote a history of the world in forty books.

[3]:

Bk. II., ch. 31, ed. Vogol, vol. i., p. 222.

[4]:

The boats used by the Babylonians and Assyrians are also described by Herodotus (Bk. I., chap. 194), who says that they were circular like a shield, their ribs being formed by willow branches and covered externally with skins, while no distinction was made between the head and the stern. At the present day similar vessels built of branches and skins, over which bitumen is smeared, are used at Baglidad. (See Layard, Nineveh and its Remains, vol. ii. p. 381.)

[5]:

See below, p. 55.

[6]:

See p. 161.

[7]:

See p. 134.

[8]:

Isaiah xiv. 10 f.

[9]:

Ezekiel xxxii. 17 ff.

[10]:

Psalm vi. 5.

[11]:

See Clermont-Ganneau, See. Archéol, A Nouv. Sér., vol. 37, p. 343 .

[12]:

See the plate published by Soheil, Recueil de Travaux, Vol. XX., p. 55.

[13]:

See Lajard, Recherches sur le culte ... de Venus, pl. XVII., No. 1.

[14]:

No. 86,262.

[15]:

See King, Babylonian Magic and Sorcery, p. 119 f.

[16]:

I cannot translate the signs in the text here.

[17]:

British Museum, No. 81-2-4, 65.

[18]:

See De Sarzeo, Découvertea en Chaldée, pi. 3.

[19]:

British Museum, K. 7856; see Meissner, Vienna Oriental Journal Vol. XII., pp. 60 ff.

[20]:

The Annnnaki.

[21]:

Cuneiform Inscriptions of Western Asia, Vol. V., pl. -vii., II. 38 if.

[22]:

Bk. I., chap. 198.

[23]:

See Budge, The Mummy, p. 183.

[24]:

See Budge, The Life and Exploits of Alexander the Great, Vol II, P- 349 f.

[25]:

See Brit. llus. MS. Oriental 678, fol. 17a, col. 1.

[26]:

See Koldewey, Zeitschrift fur Assyriologie, Bd. II., pp. 403 ff.