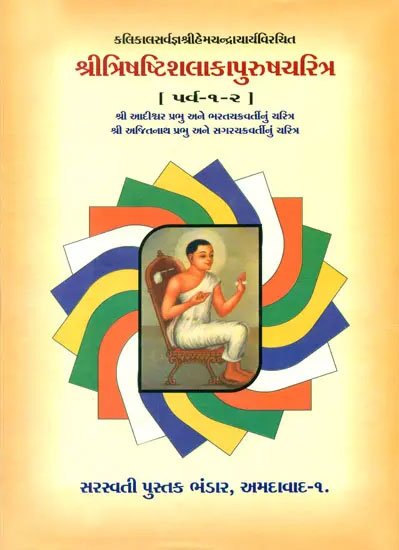

Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra

by Helen M. Johnson | 1931 | 742,503 words

This page describes Conquest of Varadamatirtha by Bharata which is the third part of chapter IV of the English translation of the Adisvara-caritra, contained within the “Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra”: a massive Jain narrative relgious text composed by Hemacandra in the 12th century. Adisvara (or Rishabha) in jainism is the first Tirthankara (Jina) and one of the 63 illustrious beings or worthy persons.

Part 3: Conquest of Varadāmatīrtha by Bharata

At the end of the eight-day festival the cakra-jewel, exceedingly brilliant as if it had fallen from the Sun’s chariot, advanced in the sky. Then the cakra went to Varadāmatīrtha in the south and the Cakravartin followed it, like pra, etc., a root.[1] Going by daily marches of a yojana, the King arrived gradually at the southern ocean, like a king-goose at Mānasa. The King established his soldiers on the southern ocean’s bank, which was covered with cardamon, clove-trees, lavali-creepers and kakkola plants. At the Cakravartin’s command, the carpenter made houses for all the army and a pauṣadha-house as before. Directing his mind on the deity of Varadāma, the King made a four days’ fast, and undertook the pauṣadha-vow in the pauṣadha-house. At the end of the pauṣadha, the King went outside the pauṣadha-house and the best of bowmen, took up the bow, Kālapṛṣṭha.[2] The King mounted his chariot made entirely of gold, studded with crores of jewels, the abode of the Śrī of victory. The chariot occupied by the King, whose form was exceedingly noble, shone like a temple occupied by a god. The best of chariots, decorated with pennants fluttering in a favorable wind, entered the ocean like a boat. After going into the ocean until the water was up to the chariot’s hub, the chariot stopped, the horses stumbling, the charioteer in the forepart of the chariot.

Then the King bent the bow and joined the arrow to the bow-string as an ācārya joins his disciple to merit.[3] He made the bow-string twang like the sound of the benedictory stanza at the beginning of the action of the play of battle, a charm for summoning death. Drawing the arrow, the thief of the beauty of the tilaka made on the forehead, from the quiver, the King set it on the bow-string. The King brought the arrow, which conveyed the impression of an axle in the center of a wheel made from the bow, up to the end of his ear. The King discharged the arrow, which had come to the end of his ear as if wishing to say, “What am I to do?” at the Lord of Varadāma. The arrow, beheld with terror by the mountains under the impression that it was a falling thunderbolt, by the serpents thinking it Garuḍa, and by the ocean thinking it another submarine fire, making the sky very bright, fell like a meteor in Varadāma’s assembly, after it had gone twelve yojanas. When he saw the arrow, like a man sent by an enemy to make destruction, fall before him, the King of Varadāma was enraged. The Lord of Varadāma, resembling an overflowing ocean with his eyebrows agitated like waves, spoke an unrestrained speech. “Who has touched the sleeping lion with his foot and awakened him today? Whose (name-) paper was turned up today by Death to have it read? Or who, disgusted with life like a leper, threw this arrow into my assembly with violence? With this very arrow, I shall kill him.” Saying this, the King of Varadāma, possessed by a demon of anger, arose and took the arrow in his hand.

Then the Lord of Varadāma, like the Lord of Māgadha, saw the words there on the Cakrin’s arrow. When he had seen these words, the Lord of Varadāma at once became calm, like a snake that had seen a nāgadamanī-plant,[4] and spoke as follows: “Like a frog eager to give a slap to a black snake; like a ram desiring to strike an elephant with its horns; like an elephant wanting to throw down a mountain with its tusks; I, feeble-minded, wish to struggle with the Cakravartin Bharata. May-nothing of ours be destroyed today.” Saying this, he ordered his people to bring divine gifts. Then taking the arrow and wonderful gifts, he went to the son of Ṛṣabha, as Indra went to Śrī Ṛṣabha-bannered. Bowing, he said to him, “Today I have come here summoned by the arrow as if by your messenger, O Indra of the earth. That I did not come of myself to you come here, O King, pardon me, ignorant, for that. Ignorance covers a fault. Now you have been attained as master by me who had no master, like a refuge by a tired man, like a full pond by a thirsty man, O Master. From today, O Lord, established here by you, I shall remain guarding your boundary, as a mountain guards the ocean-shore.” With these words, feeling intense devotion to the Lord of Bharata, he handed over the arrow like a deposit previously made. He gave the King a jeweled girdle which lighted up the sky radiantly as if woven from the light of the sun. Before the Lord of Bharata he made a shining heap of pearls, like his own glory collected over a long period. He gave the King a heap of jewels which had a dazzling, spreading light like the ocean’s wealth. The King took all that, and favored the Lord of Varadāma and established him in that very place like a monument to himself. After speaking graciously to the Lord of Varadāma and dismissing him, the victorious King went to his own camp. After descending from the chariot and having a bath, he took food with his people at the end of the four days’ fast, the moon of kings. Then he made an eight-day festival in honor of the Lord of Varadāma. The powerful exalt their own people for the sake of giving prestige (to themselves) in the world.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

From our point of view, of course, a Sanskrit preposition, precedes a root, but considering the sentence as a moving object the root goes in advance.

[2]:

I am in doubt whether this should be taken as a proper name, as I find no other reference to Bharata’s bow being so named. It occurs again in 5.410. Perhaps, it should be taken as an adjective in its etymological sense. But, Hem. (Abhi. 3.375) interprets it as meaning, ‘having death at its back,’ not ‘black-backed.’

[3]:

There is an untranslatable pun here on adhiguṇam, ‘bow-string’ and adhi guṇam.

[4]:

The Artemisia vulgaris, or wormwood. Supposed to be an antidote for snake-bite.