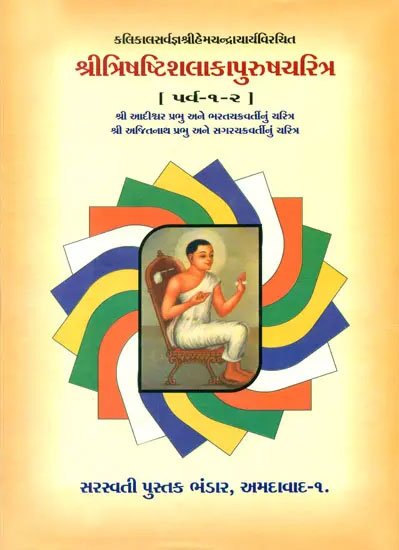

Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra

by Helen M. Johnson | 1931 | 742,503 words

This page describes Story of Udayana and Vasavadatta which is the third part of chapter XI of the English translation of the Mahavira-caritra, contained within the “Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra”: a massive Jain narrative relgious text composed by Hemacandra in the 12th century. Mahavira in jainism is the twenty-fourth Tirthankara (Jina) and one of the 63 illustrious beings or worthy persons.

Part 3: Story of Udayana and Vāsavadattā

(For a discussion of this episode, see my article, The Udayana-Vāsavadattā Romance in Hemacandra, JAOS 66 (1946), 295 ff.)

Now, King Caṇḍapradyota had a daughter, Vāsavadattā, born from Aṅgāravatī, like Śrī from the ocean. Cherished by nurses, she grew up gradually, and played in the court-yard of the palace, the Lakṣmī of the kingdom in person, as it were. The king was very devoted to her and esteemed her, covered with all auspicious marks and endowed with qualities of humility, et cetera, even more than a son. Under teachers worthy of herself she learned all the arts. The art of music alone remained without a teacher and the king asked a minister who had seen much and heard much: “Who, pray, will be a teacher for my daughter in the study of music? Generally the art of music is especially suitable for amusing the husband in the case of kings' daughters who have gone to the husband’s house.”

The minister said: “King Udayana, who is a veritable a incarnation of Tumbaru, is now the crest-jewel of the best musicians. He is reported to have a surpassing skill in music and he captures elephants in the forest, after lulling them by singing. He goes to the forest and sings and the elephants, as lulled by his singing as if they had drunk liquor are entirely unconscious of being captured. Just as he captures elephants in the forest by the device of singing, even so there is a means of capturing him and bringing him here. An elephant must be made from wood, just like a real one, in the forest there, which will make motions, walking, sitting down, et cetera, by mechanical means. Armed soldiers will stand within the wooden elephant. They will make the elephant move and they too will capture him (Udayana). After they have captured him in this way and brought him here, at your order the king of the Vatsas will teach music to your daughter Vāsavadattā.”

The minister, approved by the king saying, “Very good,” had such an elephant made that it was superior to a real elephant in its qualities. Foresters took it to be a real elephant that could bite, toss up its trunk, trumpet, walk, et cetera. Foresters described the elephant to Udayana and Udayana went to the forest to capture it. He dismissed his attendants at a distance and entered the forest, walking about very slowly as if looking for birds. When he approached the trick elephant, Udayana sang aloud, surpassing the Kinnaras;[1] and while Udayana sang a nectar-sweet song, the men inside kept the elephant motionless. The lord of Kauśāmbī thought it was lulled by his song and approached it very slowly, as if he were walking in the dark. “He has been hypnotized by my song.” With this thought, the king approached, jumped up, and mounted the elephant like a bird lighting on a tree. The soldiers, who were Pradyota’s agents, descended from the interior of the elephant, threw the king of the Vatsas from the elephant’s shoulder, and took him prisoner. Alone, unarmed, unsuspecting, surrounded by a hundred soldiers, like a boar by dogs, he did not resist.

The soldiers delivered the king of the Vatsas to Caṇḍapradyota who said to him: “Teach your own art of music to my daughter who is one-eyed. By teaching my daughter, remain comfortably in my house. Otherwise, your life depends on me, as you are a prisoner.” Udayana reflected: “I shall pass the time teaching the daughter. Verily, a living man sees fair things.” With this reflection, the king of the Vatsas—the man who indeed knew the arts—accepted Pradyota’s command.

Caṇḍapradyota said to him: “My daughter is one-eyed. Do not look at her. If you do, she will be embarrassed.” After saying this, he went to the harem and said to his daughter: “You must not look at the music-teacher who has come, because he is a leper.” Accordingly, the king of the Vatsas taught her music and they did not see each other, both of them deceived by Pradyota.

One day, the king of Avantī’s daughter was absent-minded because she was thinking, “I am going to see this man,” and recited incorrectly. Verily, conduct is subject to the mind. Then the king of the Vatsas scolded the king of Avantī’s daughter: “Why do you waste my teaching? Why are you hard to teach, one-eyed girl?” Angered by his censure, she said to the king of the Vatsas: “Why do you call me ‘one-eyed’? You do not see yourself, a leper.” Whereupon the king of the Vatsas reflected: “She is the same kind of a one-eyed person as I am a leper. Certainly I will see her.” At this thought he, quick-witted, tore down the curtain and saw her like a digit of the moon with the clouds scattered. Wide-eyed Vāsavadattā saw him with a fair body like Manmatha in person.

When Vāsavadattā had seen him and the king of the Vatsas had seen her, they gave each other a smile that indicated the growth of a mutual love. Pradyota’s daughter said: “Oh! Oh! I have been deceived by my father, sir,

I who did not see you like the moon in the darkness of amāvāsyā.[2] Teacher of the arts, you taught me all the arts thoroughly. Let them be of use to you, no one else. Be my husband.” This king of the Vatsas replied: “Fair lady, I also have been deceived by your father. I was prevented from seeing you by his concealing you with the words,

‘She is one-eyed.’ Beloved, let our union take place, even while we remain here. At a suitable time, I shall take you away, as Vainateya (Garuḍa) took the nectar.” They spoke thus in direct communication with each other in a manner charming with intelligence and the union of their bodies took place as if in emulation of the union of their minds. A slave-woman, Vāsavadattā’s nurse, a suitable depository of confidence, named Kāṭcanamālā, alone knew their behavior. Served by the slave Kāṭcanamālā alone, they lived as man and wife, unknown to any one.

One day Nalagiri pulled up his post, knocked down two elephant-drivers and, roaming as he liked, terrified the townspeople. “How is that elephant, which is controlled by no one, to be subdued?” the king asked Abhaya who suggested, “Have king Udayana sing.” Commanded by the king, “Sing to Nalagiri,” Udayana and Vāsavadattā sang to him. As a result of hearing his song, the elephant Nalagiri was thrown and made captive. Then the king gave Abhaya another boon which he kept in reserve also.

One day the king, accompanied by a train of women from the harem and of wealthy citizens, went to a garden for a picnic. At that time the minister Yogandharāyaṇa was wandering along the path, reflecting on a means of freeing the king of the Vatsas. Unable to control in his heart the burning power of his own cleverness, he spoke aloud. Generally what is in the mind is also in the speech. “If I do not take her and her and her and the long-eyed maiden for the king, I am not Yogandharāyaṇa.” Caṇḍapradyota, as he was walking, heard his clever speech and looked at him with a leering glance. Yogandharāyaṇa, who was a judge of human nature, knew at once by the gestures, et cetera, of the others that the king of Avantī was angry. First of the quick-witted, the minister adopted this expedient to disown his partisanship of the king of Kauśāmbī. He took off his upper clothing and, standing in the deformed shape of a ghoul committing a nuisance, he made it appear that he was possessed by a demon. “That is some one possessed by a demon.” The king recognized this and restrained his anger at once, like an elephant-driver restraining an elephant.

Then Caṇḍapradyota, who had a faultless voice, went into the garden and began a musical entertainment—an efficacious remedy for the elephant Smara. Eager to see new skill in music, King Pradyota summoned Vāsavadattā and the king of the Vatsas. The king of the Vatsas said to Pradyota’s daughter, “Fair lady, now is the time for us to mount the she-elephant Vegavatī and go.” At Udayana’s command the king of Avantī’s daughter at once had the she-elephant Vegavatī, that was faster than the wind, led out. As the girth was being fastened, the elephant cried out; and a blind astrologer, who heard the cry, said, “Since the elephant cries out while the girth is being fastened, she will die after she has gone a hundred yojanas.” The elephant-driver, Vasantaka, fastened four jars of urine at the sides of the elephant at Udayana’s order. Then the king of the Vatsas, holding Ghoṣavatī in his hand, Pradyota’s daughter, Kāṭcanamālā, and Vasanta mounted the she-elephant. Yogandharāyaṇa came and urged on Udayana with a gesture of his hand, saying, “Go! Go!” As he went, he (Udayana) said: “Vāsavadattā, Kāṭcanamālā, Vasantaka, Vegavatī, Ghoṣavatī and the king of the Vatsas—these are leaving.” The king of the Vatsas, urging on the she-elephant with great speed, but making this announcement, did not violate the conduct (fitting) for a warrior.

When Pradyota knew that Udayana had gone with the five, he rubbed his hands, as if he were throwing dice in gambling. The lord of Avantī, whose courage was invincible, fitted out Nalagiri loaded with elephant-drivers and soldiers and sent him in pursuit. After twenty-five yojanas had been traveled, the fear-inspiring elephant was seen by Udayana not very far away. Then Udayana had one of the jars broken on the ground and at the same time urged on his elephant. The elephant (Nalagiri) stopped a moment to sniff the contents of the jar and then, urged on by a stick, started again. The king of the Vatsas delayed the progress of Nalagiri by having the other jars broken, each at the same distance on the road. After Udayana had gone one hundred yojanas, he entered Kauṣāmbī and then the she-elephant died from exhaustion. While the elephant Nalagiri delayed to sniff the contents of the jars, the king of Kauśāmbī’s army approached to fight, whereupon the elephant-drivers turned Nalagiri and returned to Ujjayinī by the same road by which they had come.

Pradyota, a Kṛtānta from anger, began to collect an army but was prevented by the faithful ministers of the house with the argument: “Certainly, the girl will have to be given to some suitor or other. So, what better son-in-law than the king of the Vatsas will you find? Vāsavadattā herself chose him of her own free will. As a result of his good deeds, he was a suitable husband for your daughter, master. Therefore, enough of collecting an army. Accept him as her husband, since he has taken Vāsavadattā as a maiden.” Enlightened by them with this reasoning, the king, knowing what was proper, joyfully sent the king of the Vatsas a collection of gifts suitable for a son-in-law.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Heavenly musician.

[2]:

The night of complete darkness.