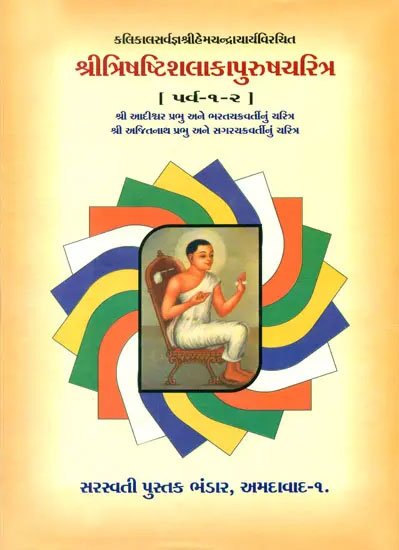

Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra

by Helen M. Johnson | 1931 | 742,503 words

This page describes Grief of the people at their death which is the first part of chapter VI of the English translation of the Ajitanatha-caritra, contained within the “Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra”: a massive Jain narrative relgious text composed by Hemacandra in the 12th century. Ajitanatha in jainism is the second Tirthankara (Jina) and one of the 63 illustrious beings or worthy persons.

Part 1: Grief of the people at their death

Then a great outcry arose from the soldiers in the Cakrin’s army, like that of sea-monsters in an ocean that was going dry. Some fell on the ground in a swoon, as if they had eaten kimpākas,[1] as if they had drunk poison, as if they had been bitten by serpents. Some struck their own heads like cocoanuts; some beat their breasts again and again as if they had committed a crime. Some, after takin g steps, stopped, confused about what to do, like women; others climbed precipices like monkeys, intending to jump. Some drew their knives, like Yama’s tongue, from their scabbards, intending to cut their own abdomens, like cutting pumpkins. Others, intending to hang themselves on the branches of trees, tied their upper-garments to them, as they had formerly tied pleasure-swings. Some tore out the hair on their heads like kuśa-grass in a field. Some threw away the ornaments on their bodies, like drops of perspiration. Some stood absorbed in thought, resting their cheeks on their hands, like a decrepit-looking wall that has a post added as a prop. Some, removing upper and lower garments also, rolled on the ground with trembling limbs, like crazy people. The women of the household uttered different lamentations, like ospreys in the air, that made the heart tremble:

“O Fate, why did you commit this half-murder, taking our husbands and leaving life in us? O goddess earth, be gracious, burst open, and give us a chasm. Surely, the earth is a refuge of those who have fallen even from a cloud. O Fate, today make fall an unexpected cruel stroke of lightning on us like lizards. O breath, for you there are happy courses. Go wherever you wish. Leave our bodies like hired tents. Come, deep sleep,[2] removing all pains; or Mandākinī, rise, and give death by water. O forest-fire, appear in this forest on the mountain. We shall follow the path of our husbands, as if from friendship for you. Oh! hair, give up friendship today with wreaths of flowers. Eyes, let a handful of water (for funeral rites) he given to you for collyrium. Cheeks, do not itch for decorations with unguent. Lip, do not desire contact with lac. Ears, abandon jeweled ear-rings, as well as listening to songs. Neck, henceforth do not long for neck-ornaments. Breasts, today a necklace is for you like snow for lotuses. Heart, fall in two pieces at once like a ripe melon. Arms, enough of bracelets and armlets like burdens for you. Hips, give up the girdle like the moon its light at dawn. O feet, enough of foot-omaments as if they had never been obtained. Body, enough of ointments as if made of cowhage.”[3]

The forests, like relatives, wept with echoes of such pathetic cries of the women of the household.

The general, the vassals, kings, etc., said various things indicating sorrow, shame, anger, fear, etc.

“Oh! Sons of our master, where have you gone? We do not know. Tell ns, that we may follow you, obedient to our master’s instructions. Or have you used some magic art of disappearance in this case? But it is not right to employ it to distress servants. How will our master look on our faces if we, like murderers of rishis, go without you who are lost or vanished? The world will ridicule us if we go now without you. O heart, burst at once like a pitcher of unbaked clay wet with water. Halt! Halt! rogue of a serpent! Where have you gone now, villain, after destroying by some trick, like a dog, our masters who were engaged in the protection of Aṣṭāpada? Prepare for battle, sword against sword, bow against bow, spear against spear, and club against club, O villain. How far will you go after running away?

Now these sons of our master have abandoned us here and have gone away. Oh! Oh! The master also will abandon us quickly if we go there now. When our master hears that we are alive, even if we do not go there but stay here, he will be ashamed, or rather, will punish us.”

Return to Ayodhyā:

After uttering many such lamentations, they joined each other again and, after regaining their natural firmness, took counsel together. “Just as a rule in grammar subsequently laid down takes precedence over rules given earlier,[4] so fate is stronger than all. No one is stronger than it. The desire to retaliate against it which is not subject to retaliation is useless, like a desire to strike the sky or to seize the sun. So, enough of these lamentations. Now we shall deliver everything belonging to the lord, horses, elephants, etc., like trustees surrendering money. Thereafter let the master arrange whatever is suitable and agreeable in regard to us. Why should we worry?”

After these reflections, they all set out to Ayodhyā with sad faces, taking with them everything, the women of the household, etc. Slowly, slowly, bereft of energy, they came to the vicinity of Ayodhyā, their faces and eyes dejected, as if they had just risen from sleep. They stopped there, as crushed as if they were being led to the execution-rock,[5] sat down on the ground and said to each other: “We were assigned by the King who honored us with his sons because we were formerly devoted, wise, powerful, and of proved ability. Returning without the princes, how can we, like men whose noses have been cut off, raise our faces in our master’s presence? How can we tell the King such news about his sons which resembles an unexpected stroke of lightning? Henceforth, alas! it is not fitting for us to go there. However, death is a suitable refuge for all suffering ones. Of what use is life, like a miserable body, to a man who has destroyed the esteem felt by his lord? Moreover, if the Cakravartin should die from hearing of the death of his sons, painful to bear, then, indeed, death would go in front of us.”

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

The Tricosanthes, which has a very disagreeable taste.

[2]:

Mahātandra (?).

[3]:

Kapikacchū. Its contact causes irritation.

[4]:

See I, p. 342 and note 384.

[5]:

A very usual method of execution in India formerly was to hurl the condemned from a precipice.