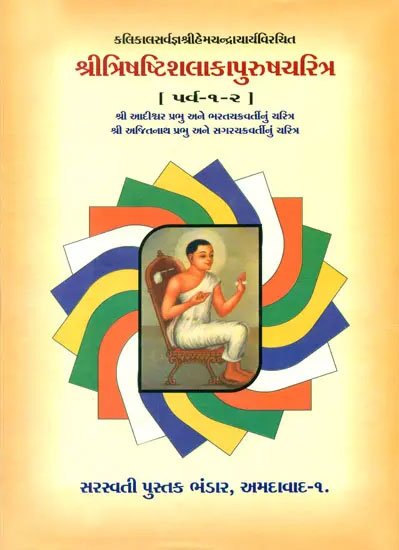

Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra

by Helen M. Johnson | 1931 | 742,503 words

This page describes Ajita’s wandering which is the eleventh part of chapter III of the English translation of the Ajitanatha-caritra, contained within the “Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra”: a massive Jain narrative relgious text composed by Hemacandra in the 12th century. Ajitanatha in jainism is the second Tirthankara (Jina) and one of the 63 illustrious beings or worthy persons.

Part 11: Ajita’s wandering

The Blessed One wandered over the earth with unhindered progress like the wind, with carefulness in walking unbroken. Presented here with rice pudding and other things free from life;[1] there his lotus-feet anointed with pleasant ointments; awaited here by laymen’s sons paying homage; followed there by people unsatisfied in looking at him; with auspicious waving of garments made by the people in some places; at other places given a reception-gift of curds, dūrvā-grass, unhusked rice, etc.; here urged by the people to permit them to lead him to their own homes; there his progress impeded by people falling on the ground; sometimes his lotus-feet wiped by the laymen with their hair; sometimes begged for instruction by the simple-minded people; free from possessions, free from self-interest, indifferent to the world, the Master wandered over the earth, turning villages and cities into sacred places from association with himself.

Lord Ajita wandered at will, his mind unshaken—just as it was in the villages and cities—on big mountains and in big forests terrifying from the hootings of owls, with jackals giving loud howls, cruel from the hissing of serpents, with cats excited and yowling, formidable with howling wolves living very cruelly on deer, echoing with varieties of cries of tiger-families, with screams of crows flying from trees split by huge elephants, with rocks and ground burst open by blows from a multitude of lions’ tails, with paths filled with bones of large elephants crushed by śarabhas, echoing with the sounds from the bows of Śabaras engaged in hunting, with Bhilla-boys occupied in seizing bears’ ears, and with fires starting from tree-tops rubbing together.

The Lord, naturally resolute, practiced kāyotsarga with ease, sometimes, motionless as another peak on a mountain-top, resembling a conquered person gazing at the ground only; sometimes on the bank of a great river like a tree with joints broken by troops of leaping monkeys; sometimes in a cemetery filled with formidable Vetālas, Piśācas, and ghosts at play, with pollen of flowers blown about by the wind; and in other places more terrifying than the Raudras.[2] Sometimes the Blessed One, Lord Ajita, observed a one day’s fast, sometimes a two days’ fast, or three or four days’ fast; at one time a fast of five days, at other times fasts of six, seven, or eight days; sometimes a fast of one month, of two, three, four, five, six, seven, up to eight months, while he was wandering in the Aryan countries, his powers undiminished.

Even in the hot season when the heat of the sun was burning his forehead, indifferent to the body, he did not desire even the shade of a tree. In the winter season when the trees were filled with a load of falling snow, the Lord did not desire a fire, like a person with burning bile. The Lord was not disturbed by the torrents, made powerful by strong winds, from the clouds, like a river-ranging elephant.[3] He endured also other trials hard to endure, enduring all like the earth, a tilaka (himself) on the earth.

The Lord spent twelve years enduring trials with severe and manifold penances and with numerous vows.[4]

The Master, never settled like a rhinoceros,[5] solitary as the horn of a rhinoceros,[6] motionless as Sumeru, fearless as a lion, unrestrained as the wind, his gaze fixed on one object like that of a serpent, his luster being increased from penance like gold from fire; surrounded by the three controls like a choice tree by hedges; observing the five kinds of carefulness, like Dhanvin (Love) carrying five arrows in his hand; meditating on the fourfold meditation—the teaching of the Jinas, the difficulties arising from love, hate, and delusion, the results of karma, and the form of the universe,[7] having a form himself worthy to be meditated on,[8] wandering in villages, cities, and forests, the Lord gradually approached the grove Sahasrāmravaṇa.

Footnotes and references:

[2]:

A class of evil spirits.

[3]:

Cf. MI. 1. 29 and Edgerton, 4n, 49-50.

[4]:

Abhigraha. See I, n. 102.

[5]:

Hemacandra’s observations in regard to natural history are usually very accurate, but anāsīna seems inapt. The rhinoceros, in captivity at least, does lie down and rest. Anāsīna must refer to its wandering about and not settling down in one place.

[6]:

Cf. khagga, Pali Text Society lexicon, for comparison of a Pratyekabuddha with a rhinoceros-horn. In the older works the comparison is incorrectly interpreted as being with the rhinoceros itself.

[7]:

The four divisions of dharmadhyāna. See below, this chapter.

[8]:

I.e., as a Tīrthaṅkara. See I, n. 409.