Bhagavati-sutra (Viyaha-pannatti)

by K. C. Lalwani | 1973 | 185,989 words

The English translation of the Bhagavati-sutra which is the fifth Jaina Agama (canonical literature). It is a large encyclopedic work in the form of a dialogue where Mahavira replies to various question. The present form of the Sutra dates to the fifth century A.D. Abhayadeva Suri wrote a vritti (commentary) on the Bhagavati in A.D. 1071. In his J...

Part 17 - On harm to self, to others, to both, to none

Q. 47. Bhante! Are the living beings harmful to self, harmful to others, harmful to both or harmful to none?

A. 47. Gautama! Some of the living beings are harmful to self, to others, to both self and others, and are not free from doing harm. Some other living beings are not harmful to self, not so to others, nor to both, but are free from doing harm.

Q. 48. Bhante! Why do ye say so?

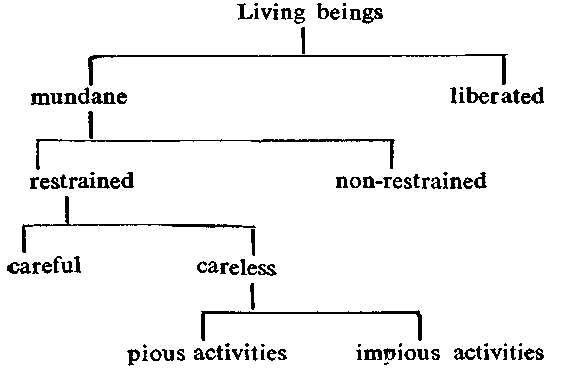

A. 48. Gautama! The living beings are stated to be of two types—those belonging to the worlds, and those not belonging to the worlds. Now, those who do not belong to the worlds are the perfected ones; and they are not harmful to self, nor so to others, nor to both self and others, but are wholly free from doing any harm. The mundane beings (in contrast) are stated to be of two types, viz., the restrained and the non-restrained. Of these, the restrained beings are stated to be of two types, viz., those who are careless and those who are careful. Now, those who are restrained-careful, they are neither harmful to self nor to others nor to both, but are free from doing harm. The restrained-careless are, from the standpoint of pious activities, neither harmful to self, nor so to others, nor to both, but are free from doing harm; but from the standpoint of impious activities, they are harmful to self, so to others and to both self and others, and are not free from doing harm. The non-restrained, are (in contrast,) on account of their not having renounced43, harmful to self, harmful to others, harmful to both self and others, and are not free from doing harm. So do I say, oh, Gautama, some of the living beings, etc., etc.,...till free from doing harm44.

Q. 49. Bhante! Are the infernal beings harmful to self, harmful to others, harmful to both or harmful to none?

A. 49. The infernal beings are harmful to self, harmful to others, harmful to both, and are not free from doing harm. And so...till the Asurakumāras.

Q. 50. Bhante! Why do ye say so?

A. 50. Gautama! It has been so stated of the infernal beings on account of their not renouncing,...till not free from doing harm. And so till the Asurakumāras...till five-organ non-human beings.

51. Human beings (to be taken) as other living beings (as aforesaid), but the liberated-bodyless are to be excluded.

52. From the Vāṇavyantaras...till the Vaimānikas, they are similar to the infernal beings.

53. The tinged souls45 are (similar to) the mundane beings. Those with black, blue and ash tinges are (similar to) the mundane beings, with the qualification that the distinction between the careful and the careless is not applicable here. (For, they are all careless without exception.) Those with red, pink and white tinges are also (similar to) the mundane beings, though exception is to be made of the liberated-bodyless (who are without any tinge).

Notes (based on commentary of Abhayadeva Sūri):

43. The word abirai in the Sūtra is important, as it throws light on one of the Jaina sanctions. According to it, it is not enough that one is habitually restrained. What is important is that he must formally renounce. If he does not, then the possibility of his transgressing the restraint remains open and the fellow cannot be deemed to be wholly restrained.

44. Presented in a tabular form, it looks as follows:

45. Leśyā is tinge taken by the soul in accordance with its karma which, in turn, indicates the extent of spiritual development of the soul. The use of tinge-names to indicate spiritual growth was popular with the Jainaś, as also with several other religious sects in this country. One comes across the term at various places in the canonical texts. It is stated to take two forms, objective and subjective. The objective form called dravya leśyā signifies the tinges accompanying various gross and subtle physical attachments of the souls, while the subjective form called bhāva leśyā is the corresponding state of the soul, of which dravya leśyā is the outward expression. Being composed of matter, dravya leśyā has all the properties of matter, viz., colour, taste, smell and touch.

Six tinges or colours of the soul have been identified by the Jainas as follows:

The behavioural pattern as per tinges may be illustrated with reference to a tree with ripe fruits on. It may be stated that in order to enjoy the fruits of the tree, people with black leśyā want to uproot the tree, people with blue leśyā are satisfied with the upper portion of the tree sparing its trunk and roots, people with grey leśyā remain contented with the fruit-bearing branches only, people of red leśyā want to tear off only the fruit-bearing stalks with fruits on, people of pink leśyā are happy to pluck only the ripe fruits and people of white leśyā want nothing mere than the fruits that have themselves dropped on the ground. The behavioural pattern is expressive of the different stages of the soul, from the least developed to the most. In the present context, the discussion centres round the tinges of the souls of the careless and the careful, the restrained and the non-restrained, those with pious activities and those with impious activities.