Jain Remains of Ancient Bengal

by Shubha Majumder | 2017 | 147,217 words

This page relates ‘General Introduction’ of the study on the Jain Remains of Ancient Bengal based on the fields of Geography, Archaeology, Art and Iconography. Jainism represents a way of life incorporating non-violence and approaches religion from humanitarian viewpoint. Ancient Bengal comprises modern West Bengal and the Republic of Bangladesh, Eastern India. Here, Jainism was allowed to flourish from the pre-Christian times up until the 10th century CE, along with Buddhism.

General Introduction

The study of historical geography is one of the essential components for better understanding of the different historical events of a region. Historical geography covers the domain of geography as a part of social-historical formation. Both history and geography play an important role in the formation and development of society, religious ideologies, polity and economy. The basic objective for the study of historical geography is to identify the various geographical changes through time and space and correlate it to socioreligious and economic changes, if any resulting from the said changes, in the reconstruction of regional history. Needless to emphasize, a region as a geographical unit is a historical construct whose boundary is defined and redefined by the contemporary political and cultural conditions. Geographical features cannot be a sole determinant of the boundary, though they may have implication to its historical formation. Conversely, our geographical delineation of a region reflects our perception of it as a historical entity.

In this chapter, I would like to discuss how one can delineate the geographical setting and its related aspects with reference to the study area. The territory, covered by the present study area, has been variously described in the extant archaeological and historical literature of Eastern India as the “Lower Gangetic Delta”, the “Lower Ganga Plain”, the “Bengal Delta” and “Ancient Bengal”. In this context it should be mentioned here that the present study region may not be profitably defined in terms of any rigid physical/political boundaries.

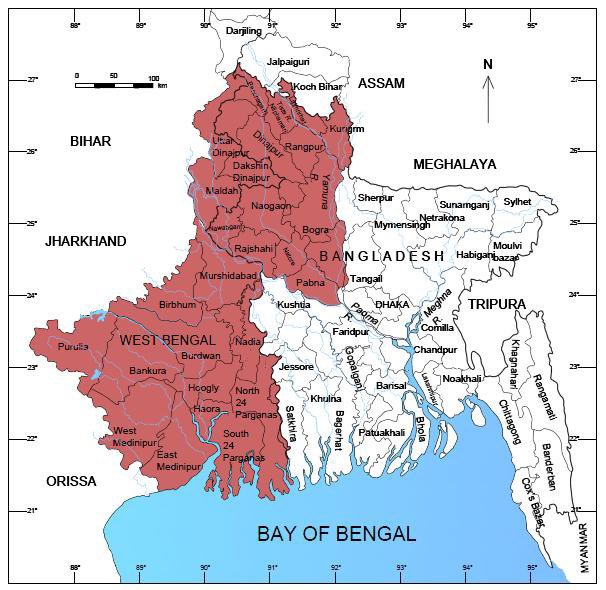

Ancient Bengal dealt with here is a region approximately corresponding to the present territories of West Bengal and the republic of Bangladesh (particularly the north-western parts i.e., the Rangpur and Rajsahi divisions mainly the districts of Dinajpur and Rajsahi[1]) (Fig. 2). These two districts are adjunct to the districts of Murshidabad and South Dinajpur of West Bengal.

Figure 2.2. Map showing the present study area (with colour).

The entire region comprises almost exclusively of alluvial plains and deltas, surrounded by the Chhotanagpur and Rajmahal hill tracts in the west, the Himalayan tarai in the north and finally the Bay of Bengal in the south. For co-relating the geo-political units of the study area with the different geographical orbits, one must consider the three separate geographical areas that partially contribute to the present spatial configuration of this region. Of these the first is lower Ganga plain encompassing “the Kishanganj tahsil of Purnea district (Bihar), whole of the West Bengal State (excluding the Purulia district and mountainous parts of the Darjeeling district) and most of the East Pakistan as well (Singh 1971:252). Another section comprises the Chhotanagpur plateau region, which includes “the Palamau, Ranchi, Hazaribagh, Giridih, Singhbhum and the Santal Parganas districts in Bihar (at present these districts are the part of Jharkhand[2]) and the Purulia district in West Bengal” (Chakrabarti 1993:1). The remaining comprises “the mountainous parts of Darjeeling”, which is West Bengal’s vestibular connection with the north-northeast: the northern sector of the State running across the Malda-Dinajpur alignment “is linked to the tarai region of Darjeeling, Jalpaiguri and Cooch Bihar, once reputedly malarial and swampy but now given over mostly to forests and tea-cultivation…. On the east the tarai is bordered by the Goalpara district of the Brahmaputra plain of Assam” (Chakrabarti 2001: 1-2). Thus, the present administrative horizon of ancient Bengal may conveniently be viewed in terms of these three combined geographical entities. It is in the light of this identity that the present work attempts at a reconstruction of the historical settlements which were closely associated with the growth and development of Jain ideology in this concerned territory.

Before entering into the details about the different geo-political units of ancient Bengal and their association with the development and spread of Jainism, we must acquaint ourselves with general physiographic configuration of the study area. This knowledge will help us to recognize the formation and subsequent spread of human settlements through the course of history in the study area.

It was probably R.K. Mookerji who precisely estimated the correlative physiography of the present study area in the context of the early economic history of the region. Although Mookerji’s classificatory scheme precludes a spatial relationship of physiography and hydrography, the categorization remains fairly relevant for a study aiming at historical archaeology of Bengal or any of its segments. The three “natural regions” of physiographic distinction for Mookerji were: (i) the Old Delta divisible into West Bengal and Central Bengal, (ii) the New Delta or East Bengal, (iii) the Ganges-Brahmaputra Doab or North Bengal (Mookerji 1938:116). The view of Mookerji was modified by Amitabha Bhattacharyya in his study of the early-early medieval historical geography of Bengal, though in terms of hydrography again, with more clear geographical insight.

Bhattacharyya thus remarks:

Physiographically considered, Bengal thus comprises the alluvial plains of North Bengal, those between the Brahmaputra and the Meghna, the deltaic region between the Bhāgīrathī and the Meghna and sub-montane tracts of the Chittagong and Burdwan divisions (Bhattacharyya 1977: 13).

However, in this context it should be mentioned here that K. Bagchi in his work tried to show that the deltaic features associated with the relation to physiography are to be found only in the composite landmass bounded by the Padma in the north, the Bhagirathi in the west and the Meghna in the east (Bagchi 1944:18, see also Bagchi 1972).

The present day general physiographic divisions of West Bengal are (1) The Plain, (2) the High Plain and (3) the Hills (Banerjee 1969: 119-28). Each of these divisions though constituted of broad physiographic zones, have different, comparatively smaller regional components. If we consider the spread of Jainism in ancient Bengal then we find that Jainism had spread both in the upland plateau region and adjoining flood plains.

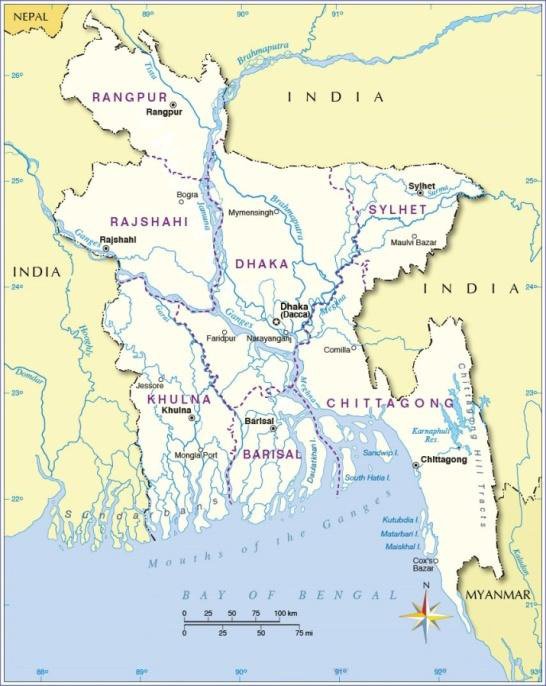

The most prominent geographical feature in this low land is its river system, mainly constituted by the great rivers Ganga and Brahmaputra, and their tributaries and distributaries. All the three major physiographic divisions of ancient Bengal are characterized by a complex and often complicated network of a large number of rivers and rivulets. The high plains and the northern most hilly regions constitute a separate hydrographic block; the western plateau extending south-easterly into the core areas of Burdwan forms another; the rest of the two major hydrographic belts are centered round the present Bhagirathi-Hooghly channel; one to the east of it and the other forming its southern extension. The hydrographic features in our study area are divided into four broad regional blocks–(a) rivers of the hills and plains of north (b) rivers to the west of Bhagirathi-Hooghly (c) rivers to the east of Bhagirathi-Hoohgly and (d) rivers of the Bhagirathi system in the coastal plains (Fig. 3 & 4).

|

|

Figures 2. 3 & 4. River systems of West Bengal and Bangladesh

The popularity and the spread of Jainism, in our study area, was inevitable inter-linked (both directly and indirectly) with the hydrographic system of ancient Bengal. The ancient routes (mainly by the rivers) that crisscrossed the different zones were well traversed by Jain monks and merchants which facilitated the proliferation of Jain ideology. In this context we may cite several Jain literary sources which refer to the spread of the Jain ideology in eastern India. Jain literary tradition ascribes Kundagrama, ancient

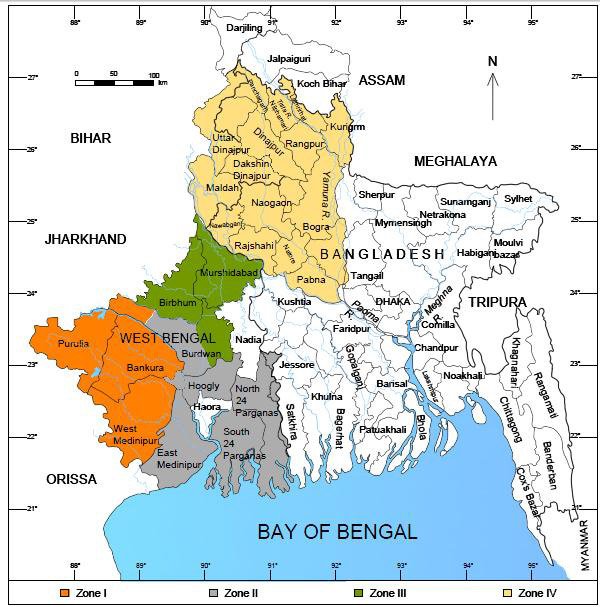

Vaishali (north Bihar) with the nativity of Mahāvīra. Several ancient Jain chronicles associate urban centres of the historical period like Mithila, Kasi, Varanasi, Rajagriha, and Champa in connection with various events in the lives of the twenty-four Tīrthaṅkaras. Evidently, the geographical unit designated as the middle Ganga plain, witnessed the genesis and spread of the Jain doctrine, philosophy and above all the ideology. However, in the present study area i.e., the lower Ganga plain was not closely connected with the early development of Jainism. However, subsequently the rivers to the west of the Bhagirathi-Hooghly system and the rivers of the Bhagirathi system in the coastal plains played a pivotal role in the wide dispersal of Jainism. So far as the geographical setting is concerned, we have divided the study area into four zones (Figs. 2.5). They include:

Zone I: The eastern fringes of the Chhotanagpur Plateau covering the present districts of Purulia, Bankura, western part of Burdwan and West Midnapur i.e., the region comprising ancient Suhma and Rāḍha.

Zone II: The coastal region or littorals or the active delta zone including its immediate hinterland area covering the modern districts of East Midnapur, North and South Twenty Four-Parganas, Howrah, Hooghly and some parts of south-east Burdwan, i.e., the region comprising ancient Vaṅga though this zone was also a part of Suhma.

Zone III: The sector along the western bank of the Bhagirathi including the Mayurakshi Plain covering the present districts of Murshidabad, Birbhum and the north-eastern and central parts of Burdwan, i.e., the region included in ancient Vardhamāna-bhukti, Uttar Rāḍha, Kaṅkanagrāma-bhukti.

Zone IV: North Bengal including that part of the Mahananda Plains comprising the modern districts of Darjeeling, Jalpaiguri, Cooch Behar, North and South Dinajpur and Malda besides, the Rangpur and Rajsahi divisions mainly the districts of Dinajpur and Rajsahi of modern Bangladesh. This region was popularly known as Varendrī and apparently the ancient geopolitical unit known as Puṇḍravardhana-bhukti.

Figure 2.5. Map showing the four different zones of the present study area

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

The rationale behind the inclusion of the districts of Dinajpur and Rajsahi (presently in Bangladesh) is that both these district yielded significant Jain antiquities which should be studied with reference to the Jain sculptural remains of ancient Bengal. Most of these Jain sculptures (from these two districts) may be classified under the early phase of Jain sculptural activities in ancient Bengal.

[2]:

The new state of Jharkhand was inaugurated for administrative functioning on 15th November 2000. This new state, covering the core area of the Chhotanagpur plateau, was bifurcated from the earlier state of Bihar. It comprises with the older districts of Palamau, Ranchi, Singhbhum, Hazaribagh, Giridih, Dhanbad and Santhal Parganas.