Matangalila and Hastyayurveda (study)

by Chandrima Das | 2021 | 98,676 words

This page relates ‘Influence on foreign countries’ of the study on the Matangalina and Hastyayurveda in the light of available epigraphic data on elephants in ancient India. Both the Matanga-Lila (by Nilakantha) and and the Hasti-Ayurveda (by Palakapya) represent technical Sanskrit works deal with the treatment of elephants. This thesis deals with their natural abode, capturing techniques, myths and metaphors, and other text related to elephants reflected from a historical and chronological cultural framework.

Influence on foreign countries

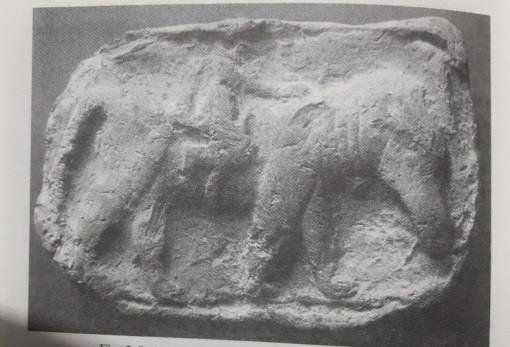

One of the earliest depictions of taming of elephants is portrayed on a terracotta image from Mesopotamia to which Trautmann draws out attention.[1] Leonard Woolley and Max Mallowan have published this image in their report with a caption “A man riding an elephant”. If the interpretation is correct it would be the one and only direct evidence of the riding of tamed elephants as early as second millennium BCE–anywhere among the early civilizations, which should be compared with a similar scene of a man riding a humped bull.[2]

[25. A man riding an elephant]

[26. A man riding a humped bull]

Leon Legrain rightly points out that:

“….this is a rare but curious witness to the influence of Indian trade and models in the Larsa period. The animal is represented as walking. Its straight back, small ears and thick legs belong to the Indian types.[3] Like those portrait on Indian seals it shows no traces of tusks and may be a female. On this relief the tail is somewhat long and the trunk is rolled up as if collecting fodder; the marks around the neck may be folds of skin, or necklace. The mode of riding is still more curious. A broad woven strap, as used today in India to fix the howdah, is tied round the body of the animal. The driver is siting neither on the head nor on the back, but is represented at mid flank in an almost impossible position, with his right knee stuck below the strap. This is exactly the position of the man riding on the back of an Indian humped bull on a relief plaque from Ischali, here transformed into an elephant rider. On both reliefs bust and arms are shown full-face, the left hand resting on the hump or shoulders of the animal, the right holding a slightly curved driving stick; both riders are nude except for a light loincloth and girdle”.[4]

This cannot be considered as a howdah since the howdah was a late invention. Legrain later also pointed out that this work was that of an artist who had no practical knowledge of the elephant and had not seen an elephant rider. It was all from his imagination and hence the artist portrayed the elephant rider was simply an imitation of the bull rider.[5]

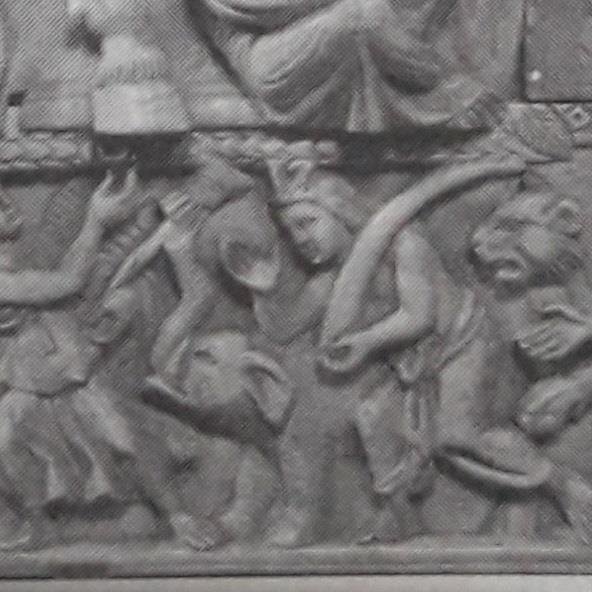

Elephants figured both in Sassanian representations and in those of their Roman adversaries. In a Sassanian relief at Bishapur III, Romans and Kuṣāṇas appear before the Persian king carrying gifts, those of the Kuṣāṇa include two wild cats on leashes (perhaps tigers) and an elephant. In this Sassanian representation the elephant is a sign of India; while in Roman representation the elephant though certainly Indian in origin, functions as an emblem of Persia, as in a triumphal arch in Thessaloniki, Greece, celebrating the victory of the Roman emperor Galerius over the Persians at Satala (298 CE). In one panel Sassanian figures bearing gifts are accompanied by three elephants with māhuts and one large feline, this was probably a gift of the Kuṣāṇas to the Sassanians at Bishapur.

[27. Persians bringing tributes, Arch of Galerius, Thessaloniki, Greece. Courtesy: Thomas R. Trautmann]

In another representation, called the Barberini ivory, there is a central panel celebrating the victorious emperor Justinian with gift-bearing figures of Persians. The gifts include an elephant, a large tusk, and what looks like a tiger–typical products of India as they were for the Romans.[6]

[28. Another representation of Persians bringing tribute, Barberini ivory. Courtesy: Thomas R. Trautmann]

[29. The ivory and an elephant. Courtesy: Thomas R. Trautmann]

It is evident that Indian hunters and trainers were acquired by Alexander and sought by his Hellenistic successors, and that Indian māhuts travelled with Indian elephants as far as the Seleucid kings of Syria and the Ptolemaic kings of Egypt–and possibly further. The demand of māhuts or elephant drivers and trainers is seen throughout the ancient and medieval times. There is circumstantial evidence that North Indian māhuts, transmitted their knowledge to locals in South India, and that the māhuts of India trained those in Sri Lanka and South Asia.[7] There is direct evidence that South-East Asian māhuts accompanied diplomatic gifts of elephants by South-East Asian kings to the emperor of China in Ming times. These show that the unwritten knowledge of the māhut in particular, as also of the hunter and the trainers is a crucial strategic asset for kings using war elephants, and that it was embodied in and spread by Indian māhuts, hunters and trainers.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Thomas R. Trautmann. Elephants and Kings An Environmental History, p. 79.

[2]:

Ibid., p. 81. Picture courtesy for picture no. 25 & 26–Thomas R.Trautmann.

[3]:

E.J.H. Mackay, Further Excavations at Mohenjo-daro, Delhi, 1938, p.329.

[4]:

Leonard Woolley and Max Mallowan. Ur Exacavations, Vol. VII; The Old Babylonian Period, ed. T.C. Mitchell. British Museum Publications, 1976, p. 182.

[5]:

Leon Legrain. “Horseback riding in the third millennium BC”, University Museum Bulletine, University of Pennsylvania, 11.4, 1946, p. 29. According to the author he is “represented in an impossible position, sitting neither on the head nor on the neck, but hanging mid-flank on one side, his left resting on the shoulders, his right armed with a short curved stick, simply hanging motionless.”

[6]:

Thomas R. Trautmann. Elephants and Kings An Environmental History, p.255.

[7]:

Thomas R. Trautmann. Elephants and Kings An Environmental History, p.141