Matangalila and Hastyayurveda (study)

by Chandrima Das | 2021 | 98,676 words

This page relates ‘Airavata (vehicle of the King of Gods—Indra)’ of the study on the Matangalina and Hastyayurveda in the light of available epigraphic data on elephants in ancient India. Both the Matanga-Lila (by Nilakantha) and and the Hasti-Ayurveda (by Palakapya) represent technical Sanskrit works deal with the treatment of elephants. This thesis deals with their natural abode, capturing techniques, myths and metaphors, and other text related to elephants reflected from a historical and chronological cultural framework.

Airāvata (vehicle of the King of Gods—Indra)

We already discussed the name of Aṣṭadiggajas–Airāvata, Puṇḍarika, Vāmana, Kumuda, Añjana, Puṣpadanta, Sārvabhauma, Supratīka respectively. [...]

Among all these eight elephants, Airāvata considered the chief elephant of east and vehicle of the King of Gods Indra. But the original of the Brahmanical mythology, however finds no mention in the Ṛgveda where Indra’s vehicle is always described as a golden chariot drawn by horses. Airāvata’s own grand entry is reserved for a later creation myth[1] in which a collaboration of devas (gods) and asuras (demons) churn a cosmic ocean of milk to obtain an elixir of immortality. Among the numerous sacred objects and personifications that surface from the churning is a milk-white elephant with four tusks. Each tusk symbolizes a divine quality: prabhu (sovereignty), mantra (counsel), utsāha (exuberance) and daiva (fortune). The elephant’s colour and regal bearing prompt Indra to effect a change in his mode of transport.[2]

In the later Vedic texts and ever after Indra is associated with his own vāhana, the celestial Airāvata or Airāvaṇa. how exactly this development came about is far from clear, Gonda is surely right to connect it with the rising dignity of riding horse-back in the ancient chariotusing civilizations of western Asia and southern Europe generally.[3] The salient fact is that horseback riding was of low status in the warrior culture of Vedic times, while chariot riding was of the highest status. It is possible that the invention of the war elephant contributed to improving the status of riding on the back of an animal, relative to riding a chariot.

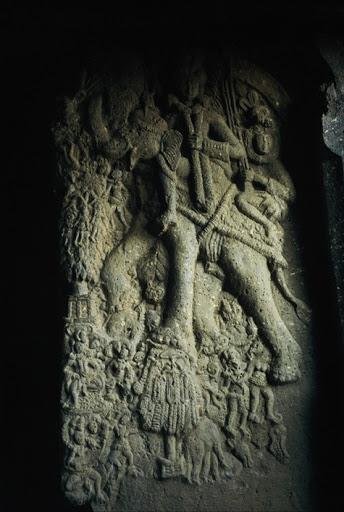

Sometimes Airāvata is considered as monsoon-cloud. In the Buddhist cave-monastery at Bhaja in Maharashtra, near Mumbai (c.2nd century BCE) bears on its right entrance a beautifully incised stone-relief which shows King of gods Indra riding on his giant elephant Airāvata, where the animal-shaped epitome of the rain-bestowing monsoon-cloud. To the left of the celestial elephant, who brings a mighty tree on his uplifted trunk which he has uprooted in his course, symbolizing the irresistible ferocity of the storm[4]. Sacred elephants (nāgas) who primitively had wings and associated with the clouds, represents even now as retainer of the power to attract their rain-bearing.

[15. Indra riding on Airāvata, Bhaja, Maharashtra]

It is worth mentioning here that in the ancient dānastuti hymns the things given as dānas are specified, which are almost always cattle, and often also gold, slaves, horses and chariots with horses–but never elephants, at least not in the dānastutis of the earliest Vedic text, the Ṛgveda. But elephants soon figure in later Vedic texts as the gifts of kings to poets or as fees to priests and other officiating at a sacrifice performed by a king. One of these later Vedic texts, the Aitareya Brāhmaṇa, celebrates the fantastically rich gift of king Aṅga to the priest who performed for him the “great anointing of Indra” (Aindramahābhiṣeka, the ritual consecration of a person as king): two thousand thousands of cows, 88,000 horses; 10,000 slave girls; 10,000 elephants.[5]

It is not difficult to demonstrate this higher dignity of the chariot–the gods themselves all ride chariots in the Veda, as we have seen, Gonda proposed that the increased importance of cavalry and growing prestige of riding horseback motivated the rise of the particular animal vāhanas associated with each Brahamanical god as its characteristic mount, abandoning the chariot for an animal conveyance specific to that god. The argument is convincing. Thus Śiva is associated with the bull Nandi; Viṣṇu with Garuḍa and Indra’s mount is the Airāvata. Only Sūrya continues to ride chariot daily across the sky, like his Greek counterpart Helios.[6]

In a variation of ocean myth, Airāvata is accountable (albeit indirectly) for the churning of the ocean. Here, the elephant already belongs to the king of gods. Epigraphic records also reflect the same references. Along with other Purāṇic treatise Mātaṅgalīlā also gives a mythical story which tells Durvāsā respectfully gave the Lord of the Gods a marvellous garland. It was crushed by Airāvata, on seeing this the sage mercilessly cursed him. By his curse he was destroyed, and then was (re-)born (as) the mate of Abhramu in the ocean when it was churned (by Indra) to win him back and to win complete supremacy. Hence he is reputed to be born of the milk ocean. Cambay plates of Govinda IV of Śaka-samvat 852 (CE 930) gives a magnificent description of the rising of Airāvata by churning milk ocean. Started with evoking Keśava (Viṣṇu), on whose person horripilation was caused by the waves which sprang up in the milky ocean agitated by the revolution of the Mandāra mountain, and which were reddened by the dense washing of quantities of red chalk of the best of the elephant. This refers to Airāvata, the elephant of Indra who was produced by the churning of the milky ocean.[7] Another inscription of Chandella’s from Mahoba, of which verse 26 records the victory of Kīrtivarman over Lakṣmīkarṇa with the description of Purāṇic myths of churning of milk-ocean. According to this record–“Just as Puruṣottama (Viṣṇu), having produced the nectar by churning with the mountain (Mandāra) the rolling (milk) ocean, whose high waves had swallowed many mountains, obtained (the goddess) Lakṣmī together with the elephants (of the eight regions), -he (viz. Kīrtivarman), having acquired fame by crushing with his strong arm the haughty Lakṣmīkarṇa, whose armies had destroyed many princess, obtained splendour in this world together with elephants”.[8]

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

“Kṣīrabdhi-manthana’ (the churning of the Ocean of Milk). Variations of the myths recur in the Agni Purāṇa, Viṣṇu Purāṇa and Bhāgavata Purāṇa and in the epics Rāmāyaṇa and Mahābhārata.

[2]:

V. Ram. Elephant Kingdom–Sculptures from Indian Architecture, p. 12.

[3]:

[4]:

Heinrich Zimmer. Myths and Symbols in Indian Art and Civilization, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1974, p. 53.

[5]:

[6]:

Thomas R. Trautmann. Elephants and Kings An Environmental History, p.122.

[7]:

EI, Vol. VII, pp. 26-27.

[8]:

EI, Vol. I, p.219.