Hindu Pluralism

by Elaine M. Fisher | 2017 | 113,630 words

This thesis is called Hindu Pluralism: “Religion and the Public Sphere in Early Modern South India”.—Hinduism has historically exhibited a marked tendency toward pluralism—and plurality—a trend that did not reverse in the centuries before colonialism but, rather, accelerated through the development of precolonial Indic early modernity. Hindu plur...

The Public Theologians of Early Modern South India

[Full title: Smārta-Śaivism in context: The Public Theologians of Early Modern South India]

Hindu sectarian communities, crystallizing in the late-medieval or early modern centuries, invoked the legacy of the past while promulgating radically new modes of religious identity. This was the south India in which the Smārta-Śaiva tradition as we know it first began to come into view and began to distinguish itself from contemporary communities of Śaivas and Vaiṣṇavas alike. Also known today as Tamil Brahminism, the Smārta-Śaiva community of the modern age has recently featured in the work of C. J. Fuller and Haripriya Narasimhan, who investigate the sociality of being Brahmin in twentieth-century Tamil Nadu; and its contemporary religious lifeworld has best been captured by Douglas Renfrew Brooks, particularly its seamless intertwining of Śaiva orthodoxy and Śrīvidyā Śākta esotericism. The history of its origins, or of how Smārta-Śaiva theologians came to speak for an emerging religious community, is a story that remains to be told. Smārta-Śaivism, it turns out, first acquired its distinctive religious culture during the generation of Appayya Dīkṣita’s grandnephew, a poet-intellectual of no small repute: Nīlakaṇṭha Dīkṣita, court poet and minister to Tirumalai Nāyaka of Madurai, devout Śaiva and ardent devotee of the goddess Mīnākṣī, and one of history’s first Smārta-Śaiva theologians.

Nīlakaṇṭha Dīkṣita is best known as one of early modern India’s most gifted poets, famed for his incisive wit and the graceful simplicity of his verse, which contrasts markedly with the heavily ornamentalist style popular in post-Vijayanagara south India. And yet, despite his considerable gifts as a poet, Nīlakaṇṭha left his lasting mark on south Indian society not as a poet but as a theologian. We know that Nīlakaṇṭha had established himself at the Madurai court during Tirumalai Nāyaka’s reign, with terms of employment that may have included both literary and sacerdotal activities.[1] On the literary side, he composed a number of works of courtly poetry, or kāvya, ranging from epic poems to hymns of praise venerating his chosen deities, Śiva and Mīnākṣī, the local goddess of Madurai.[2] He authored fewer works of systematic thought (śāstra), which include a commentary (Prakāśa) on Kaiyaṭa’s Mahābhāṣyapradīpa,[3] as well as two works of theology: the Śivatattvarahasya (The secret of the principle of Śiva), a discursive commentary on the popular Śaiva hymn the Śivāṣṭottarasahasranāmastotra (The thousand and eight names of Śiva); and the Saubhāgyacandrātapa (The moonlight of auspiciousness), a paddhati, or ritual manual of the Śrīvidyā Śākta Tantric tradition, in which Nīlakaṇṭha was initiated by the Śaṅkarācārya ascetic he names as his guru, a certain Gīrvāṇendra Sarasvatī.[4] Indeed, a number of anecdotes handed down among Nīlakaṇṭha’s descendants have preserved memory of his Śākta leanings, including the belief that Appayya Dīkṣita bequeathed to him his personal copy of the Devīmāhātmya.

Perhaps most noteworthy, however, is a legend that circulates freely among Nīlakaṇṭha’s descendants, purported to explain the passion that moved him to compose his hymn to the goddess Mīnākṣī, the Ānandasāgarastava (Hymn to the ocean of bliss). Nīlakaṇṭha, rumor has it, was employed to oversee the construction of Tirumalai Nāyaka’s New Hall, the Putu Maṇṭapam, directly outside the Mīnākṣī-Sundareśvara Temple in the center of Madurai in honor of the city’s new and revised celebration of the divine couple’s sacred marriage—a curious set of circumstances we will have the opportunity explore further in chapter 4. Among the statues commissioned to grace the pillars of the New Hall was a true-to-life figure of Tirumalai Nāyaka’s chief queen.[5] When artisans had nearly completed chiseling the final lifelike features of Madurai’s queen, a stone chanced to fall suddenly upon the statue, leaving a noticeable indentation upon the statue’s thigh. Nīlakaṇṭha, out of reverence for the divine plan of Śiva and Mīnākṣī, instructed the artisans not to correct the indentation, with full faith that such an occurrence was not possible save for Śiva’s grace, which allowed the queen to be represented as she truly was, down to the last detail. When Tirumalai Nāyaka learned of Nīlakaṇṭha’s decree, he exploded with rage at the thought that Nīlakaṇṭha could have possessed intimate knowledge of the queen’s body, as a birthmark in fact graced the queen’s upper thigh at precisely the place where the stone fell. As a result, he promptly sent his soldiers to have his minister blinded for the offense. Engrossed in meditation on the goddess at the time, Nīlakaṇṭha foresaw his fate and, in a fit of despair, seized two coals from his ritual fire and fearlessly gouged out his own eyes. Mīnākṣī, pleased with Nīlakaṇṭha’s unwavering devotion, immediately restored his sight, and Nīlakaṇṭha responded by spontaneously composing the Ānandasāgarastava in heartfelt gratitude for the goddess’s grace.

Nīlakaṇṭha’s memory, then—the legacy he left among his nineteenth-and twentieth-century descendants—centered not on his poetic prowess and famed satirical wit but on his unparalleled devotion for the goddess. But what about his own contemporaries? Was he best known in his immediate circles as poet and grammarian or as public theologian? As a member of the Dīkṣita family, early modern south India’s most noteworthy clan of scholars, Nīlakaṇṭha was situated directly at the center of textual circulation across the southern half of the subcontinent. Beyond the South, Nīlakaṇṭha maintained direct contact with outspoken representatives of the paṇḍit communities of Varanasi,[6] possibly India’s most vibrant outpost of intellectual activity during the early modern period. Perhaps it is no surprise, then, that Nīlakaṇṭha was in a position to speak more directly than any other Smārta-Śaiva of his generation to the theological disputes that irrupted in south Indian religious discourse during his lifetime and the preceding century.

On one hand, local memory preserved a keen awareness of Nīlakaṇṭha’s centrality to the intellectual networks of the period. In works of poetry authored shortly after Nīlakaṇṭha’s lifetime, we discover allusions to his influence on subsequent generations appended to transcripts of his students’ and grand-students’ compositions.

Take, for instance, the following verse recorded in a manuscript of a commentary (vyākhyā), written by one Veṅkaṭeśvara Kavi, on the Patañjalicaritra of Rāmabhadra Dīkṣita:

In which [commentary] he, Veṅkaṭeśvara Kavi, his qualified student, textualized the glory

Of Rāmabhadra Makhin, whom he describes as the Indra of the earth,

Whom Nīlakaṇṭha Makhin instructed to compose the Rāmabāṇastava,

Who, in turn, the sage Śrī Cokkanāthādhvarin made to write the great commentary.[7]

What is particularly noteworthy about this verse, among numerous others like it that refer directly to Nīlakaṇṭha and his contemporaries, is the awareness it preserves of the process of intellectual influence. Nīlakaṇṭha, as Veṅkaṭeśvara tells us, was made to compose the “great commentary” by one of his instructors in śāstra,[8] the grammarian Cokkanātha Makhin; and Nīlakaṇṭha himself in turn exerted a direct influence on the poetry of his own pupil, Rāmabhadra Dīkṣita, who, as we will see, shared many of Nīlakaṇṭha’s own religious predilections, an ideal representative of the Smārta-Śaivas of the seventeenth century.[9] It is by no means difficult, when studying early modern India, to underestimate the immediacy of the intellectual exchange taking place between scholars, comrades and antagonists alike. And yet we have ample evidence to indicate that exchange among scholars of the period had begun to take place with unprecedented rapidity; theologians setting forth provocative works of polemic, for instance, could expect a vituperative reply from an opponent within a mere handful of years. This puts us, as scholars, in a particularly advantageous position to understand just how concretely intellectual dialogue—theology being no exception—influenced the shape of extratextual society, even in the absence of the types of documentary data historians typically employ. The context, quite often, is visible in the texts themselves.

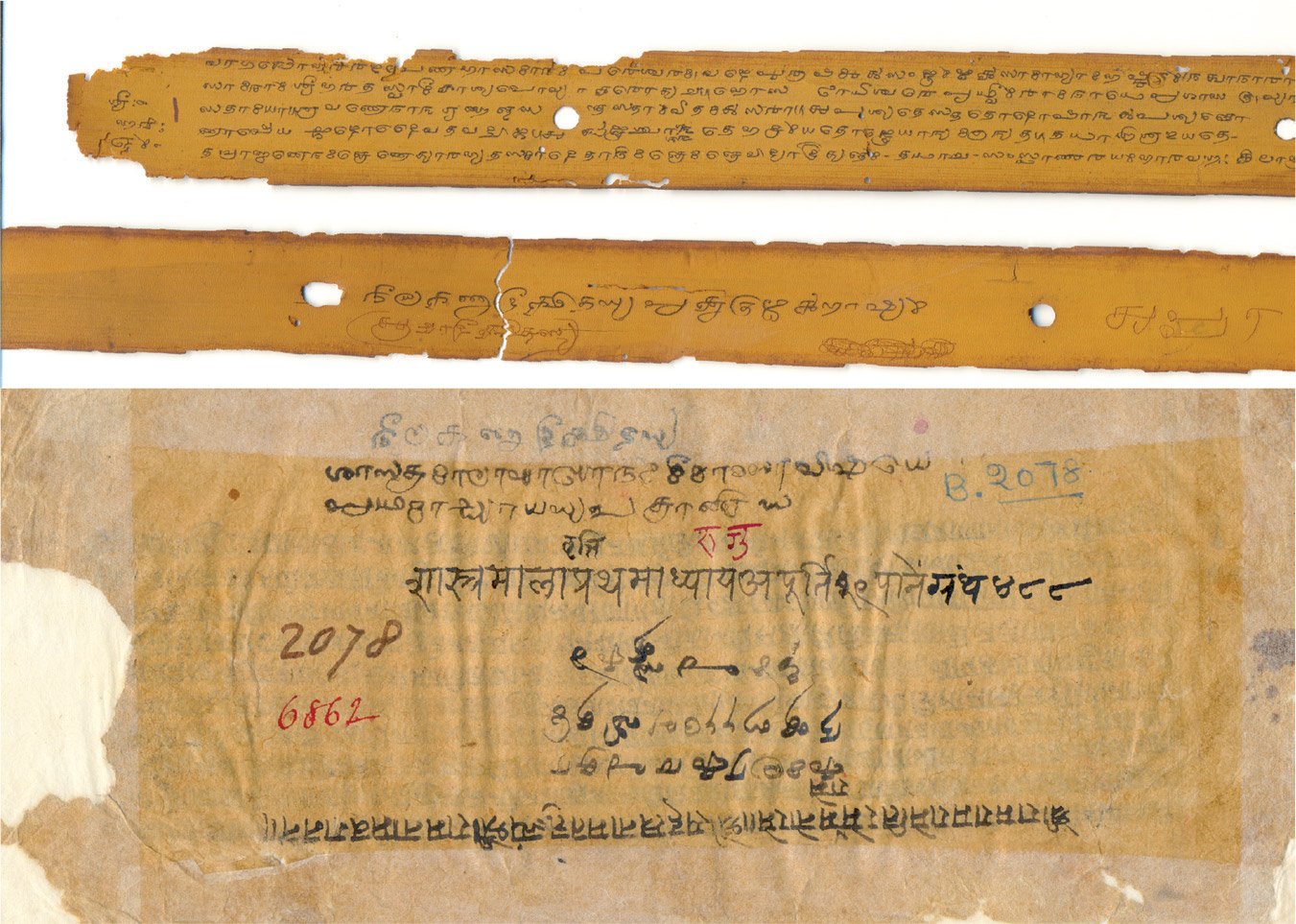

We do, on the other hand, have access to one particularly fruitful body of material evidence that speaks to the idea of Nīlakaṇṭha as an active scholar, as a portion of Nīlakaṇṭha’s personal library has in fact been preserved among the collections of the Tanjavur Maharaja Serfoji’s Sarasvati Mahal Library. These six manuscripts were certainly owned by Nīlakaṇṭha himself, as each bears what may very well be the original signature of the seventeenth-century scholar: the phrase “Nīlakaṇṭhadīkṣitasya” or “Nīlakaṇṭhadīkṣitasya prakṛti” (the copy of Nīlakaṇṭha Dīkṣita) inscribed in identical handwriting in Grantha script. On those manuscripts that were evidently handed down to Nīlakaṇṭha’s sons, we find that distinct Grantha hands have inscribed “Āccā Dīkṣitasya” or “Gīrvāṇendra Dīkṣitasya” on the very same cover folios. By far the most noteworthy of the six, however, are two Devanāgarī paper manuscripts evidently copied by scribes in north India during the seventeenth century, both the products of leading Varanasi intellectuals: select chapters of the Dinakarabhaṭṭīya, or the Śāstradīpikāvyākhyā, of Dinakara Bhaṭṭa and the Śāstramālāvyākhyāna, a work of Mīmāṃsā, of Ananta Bhaṭṭa.[10] On the latter, the Śāstramālāvyākhyāna, is written the following remarkable memorandum in yet another Grantha hand: “Kamalākaraputrānantabhaṭṭapreṣitam idaṃ pustakam.” (This book was sent by Ananta Bhaṭṭa, son of Kamalākara Bhaṭṭa.) In short, we have physical evidence to document the direct intellectual exchange between Nīlakaṇṭha and his contemporaries in Varanasi, who appear to have sent him offprints of their Mīmāṃsā works in progress for review.

FIGURE 2. Reproductions of two manuscripts bearing what appears to be the signature of Nīlakaṇṭha Dīkṣita, currently held at the Tanjavur Maharaja Serfoji’s Sarasvati Mahal Library. First manuscript: Palm-leaf cover of a Ṛgbhāṣya manuscript in Nīlakaṇṭha’s possession (D 6924). On the left we see in Grantha script the inked inscription “Nīlakaṇṭhadīkṣitasya prakṛti ṛkbhāṣyam,” and below it the uninked “āccādīkṣitasya,” suggesting that this manuscript was passed down into the possession of Nīlakaṇṭha’s eldest son, Āccān Dīkṣita. The uninked “āccā,” to the right, may be the handwriting of Āccān Dīkṣita. Second manuscript: From the Śāstramālāvyākhyāna sent to Nīlakaṇṭha Dīkṣita by its author, Ananta Bhaṭṭa (D 6862). Nīlakaṇṭha’s name is written in Grantha at the bottom in the same hand as in the first manuscript. In the center, in Grantha script, we read, “kamalākaraputrānantabhaṭṭapreṣitam idaṃ pustakam,” or “This book was sent by Kamalākara’s son Ananta Bhaṭṭa.”

Our evidence, succinctly, provides us with ample opportunity for resituating Nīlakaṇṭha in time and space, as a theologian with active networks both in his immediate locale in Madurai and across the Indian subcontinent. Historically speaking, however, our archive presents us with certain challenges in ascertaining the precise terms of Nīlakaṇṭha’s courtly employment.[11] Intriguingly, some scholars, such as A. V. Jeyechandrun, have put forth the bold assertion that Nīlakaṇṭha himself was directly involved in the ritual and logistical implementation of affairs in the Mīnākṣī-Sundareśvara Temple, including the “Sacred Games of Śiva”—entextualized in his own Sanskrit epic, the Śivalīlārṇava (The ocean of the games of Śiva). Jeyechandrun justifies this hypothesis on the basis of the excerpt from the Stāṉikarvaralāṟu, a Tamil record of the temple’s priestly families, in which we learn that a certain Ayya Dīkṣita provided direct counsel to Tirumalai Nāyaka regarding the establishment of these festivals: “Lord Tirumalai Nāyaka... established an endowment under the arbitration of Ayya Dīkṣita, instructing that the Sacred Games be conducted in the manner established by the Purāṇas.” Unfortunately, a careful reading of this passage in context renders Jeyechandrun’s conclusion unlikely, as the Ayya Dīkṣita in question most likely refers to a certain Keśava Dīkṣita, mentioned explicitly in the paragraphs immediately preceding and following this passage, whom Tirumalai Nāyaka accepted as kulaguru and assigned to the post of maṭhādhipatya in the Mīnākṣī-Sundareśvara Temple.[12] Leaving aside the issue of this particular passage, however, evidence suggests that Nīlakaṇṭha’s jurisdiction did extend far enough to include adjudicating sectarian affairs outside of the strictly literary sphere.

For instance, a direct reference to Nīlakaṇṭha’s role in moderating public intellectual debate has come down to us through Vādīndra Tīrtha, the disciple of the Mādhva preceptor Rāghavendra Tīrtha,[13] whose Guruguṇastava informs us that Nīlakaṇṭha granted an official accolade to Rāghavendra’s treatise on Bhāṭṭa Mīmāṃsā by mounting it on an elephant and processing it publicly around the city:

Just as when your treatise on the Bhāṭṭa system was mounted on an elephant

To honor you by the jewel among sacrificers [Makhin] Nīlakaṇṭha, whose doctrine was his wealth,

Your fame, O Rāghavendra, jewel among discriminating ascetics, desirous of mounting the eight elephants of the directions, has indeed of its own accord

Sped away suddenly to the end of the directions with unprecedented speed.[14]

A further record somewhat indirectly lends credence to Jeyechandrun’s hypothesis, confirming that during the reign of Tirumalai Nāyaka, Vaidika Brahmins were authorized to arbitrate temple disputes on the basis of their scriptural expertise.

This Tamil document, preserved and translated by William Taylor in this Oriental Historical Manuscripts, records an incident in which Śaiva and Vaiṣṇava arbitrators, “Appa Dīkṣita” and “Ayya Dīkṣita,” respectively, were assigned to present opposing viewpoints regarding the scriptural sanctions for temple iconography:

Having thus arranged the plan, the whole was begun to be carried into execution at once, in the tenth day of Vyasi month of Acheya year, during the increase of the moon. From that time forwards, as the master [Tirumalai Nāyaka] came daily to inspect the work, it was carried on with great care. As they were proceeding first in excavating the Terpa-kulam, they dug up from the middle a Ganapathi, (or image of Ganesa,) and caused the same to be condensed to dwell in a temple built for the purpose. As they were placing the sculptured pillars of the Vasanta-Mandabam, and were about to fix the one which bore the representation of Yega-patha-murti [Ekapādamūrti] (or the one-legged deity), they were opposed by the Vaishnavas. Hence a dispute arose between them and the Saivas, which lasted during six months, and was carried on in the presence of the sovereign. Two arbitrators were appointed, Appa-tidshadar on the part of the Saivas, and Ayya-tidshader-ayyen on the part of the Vaishnavas: these consulted Sanscrit authorities, and made the Sastras agree; after which the pillar of Yega-patha-murti was fixed in place.[15]

The remainder of this passage provides no further clues as to the identities of either of the state-sanctioned arbitrators, referred to here only by honorifics commonly employed to address Vaidika Brahmins, “Ayya” and “Appa.”[16] Historically grounded anecdotes such as these, however, provide us with invaluable information concerning the roles that court-sponsored Brahmin intellectuals such as Nīlakaṇṭha Dīkṣita were appointed to fulfill under the rule of Tirumalai Nāyaka. Much of the secondary literature somewhat uncritically proposes potential titles of employment for Nīlakaṇṭha—ranging from the English “chief minister” or “prime minister” to the Sanskrit rājaguru—without considering that such positions may not have been operative in the seventeenth-century Nāyaka states or may not have been typically assigned to Brahmin scholar-poets. While some neighboring regimes in the seventeenth-century permitted enterprising Brahmins to rise to high positions in public administration and statecraft,[17] many of these states had adopted Persianate models of governance that had made minimal inroads to the far south of the subcontinent even by the seventeenth century. Unfortunately, no evidence exists to confirm the appointment of a Brahmin minister under a title such as mantrin in the Madurai Nāyaka kingdom; the nearest equivalent, the post of pradhāni, was typically granted to members of the Mutaliyār caste rather than Vaidika Brahmins. Similarly, the strictly sacerdotal functions of a rājaguru seem to have remained in the hands of distinct lineages; the nearest equivalents under the reign of Tirumalai Nāyaka appear to have been Keśava Dīkṣita, belonging to a Brahmin family traditionally responsible for conducting the ritual affairs of the Mīnākṣī-Sundareśvara Temple, and a Śaiva lineage based in Tiruvanaikkal near Srirangam known as the Ākāśavāsīs,[18] whom numerous inscriptions describe as having received direct patronage from Tirumalai Nāyaka, and with whom the Nāyaka is alleged to have maintained a personal devotional relationship.

Strictly speaking, our textual archive remembers Nīlakaṇṭha as engaging with the world outside of the court and agrahāra through primarily intellectual means. Contemporary references confirm unambiguously that Nīlakaṇṭha presided over the city’s literary society, which sponsored the public performance of Sanskrit dramas at major regional festivals,[19] and that he was granted the authority to award official recognition to scholarly works he deemed worthy of approval, such as Rāghavendra Tīrtha’s work on Bhāṭṭa Mīmāṃsā. The precedent of the anonymous Appa Dīkṣita would suggest that Nīlakaṇṭha, as with other Smārta Brahmins under royal patronage, may well have exercised his extensive command of the Śaiva textual canon in the service of temple arbitration. In fact, citations from his Saubhāgyacandrātapa and Śivatattvarahasya indicate that Nīlakaṇṭha was uncommonly well acquainted with scriptures such as the Kāmika Āgama and Kāraṇa Āgama, principal authorities for south Indian Saiddhāntika temple ritual, and the Vātulaśuddhottara Āgama, one of the chief sourcebooks for Saiddhāntika temple iconography. While Nīlakaṇṭha may also have been regularly or occasionally commissioned to perform Vedic sacrifices, and although his intimate knowledge of Śrīvidyā was likely prized by Tirumalai Nāyaka owing to its centrality in the royal esoteric cult of south Indian kingship at the time,[20] little evidence survives to confirm these possibilities.

And yet, other mentions of Nīlakaṇṭha during his own lifetime aimed to articulate not his intellectual standing but his spiritual authority, representing him as no less than an incarnation of Śiva himself. For instance, Nīlakaṇṭha’s younger brother, Atirātra Yajvan, whom we will have occasion to meet again shortly, offers an homage to his brother’s public influence in Madurai that is less an homage to his intellectual talents than a veritable deification, as “the beloved of Dākṣāyaṇī manifest before our eyes” (sākṣād dākṣāyaṇīvallabhaḥ). It is no wonder that, within the tradition, Smārta-Śaiva theologians such as Appayya Dīkṣita and Nīlakaṇṭha Dīkṣita are recognized in the work of Appayya’s descendant Śivānanda in his Lives of Indian Saints as living divinities and honored in their villages of residents with samādhi shrines—typically the burial places of liberated saints. Such memory is echoed by many of Nīlakaṇṭha’s latter-day descendants as well, who remember the pioneering theological duo of Appayya and Nīlakaṇṭha as incarnations of Śiva and the goddess, respectively.[21]

When visiting the ancestral agrahāra of Nīlakaṇṭha’s family, Palamadai, which was said to have been granted to him by Tirumalai Nāyaka himself, a member of Nīlakaṇṭha’s family, P. Subrahmanyam, stated the following:

We are descendants of the great sage Bharadvāja. In his dynasty was born Appayya Dīkṣita, who is called the Kalpataru of Learning. He was one of the greatest men who lived in the seventeenth-century [sic], so more than three hundred years ago. And he is claimed by great people as an aṃśāvatāra [partial incarnation] of Lord Śiva himself. And then Nīlakaṇṭha Dīkṣita was his brother’s grandson—brother’s son’s son. And he is also one of the greatest people who lived later in the seventeenth century. And he’s acclaimed to be an aṃśāvatāra of Parāśakti. So we have descended from these great people.[22]

While we need not make any affirmations of Nīlakaṇṭha’s divine origin, history bears out the memory of his descendants that Nīlakaṇṭha was intimately involved in laying the groundwork of an emerging religious community, and that he became one of the first to embody a distinctively Smārta-Śaiva religious identity. As a result, I narrate the social and conceptual origins of the Smārta-Śaiva community largely through the perspective of Nīlakaṇṭha and his close acquaintances, who wrote from the focal point of an emerging sectarian community. Although Nīlakaṇṭha is remembered primarily in the Western academy as a secular poet, modern-day Smārtas in Tamil Nadu remember an altogether different Nīlakaṇṭha, one whose primary contribution to Sanskrit textual history was as a Śaiva theologian. To cite a final example, when I first discussed my research with the scholars at the Kuppuswami Sastri Research Institute in Chennai, I had scarcely mentioned Nīlakaṇṭha Dīkṣita’s name when I was met with a resounding chorus of the refrain from one of Nīlakaṇṭha’s Śaiva hymns, the Śivotkarṣamañjarī (Bouquet of the supremacy of Śiva): “He, the Lord, is my God—I remember no other even by name.”[23] Nīlakaṇṭha, as they informed me, was no less than Sanskrit literary history’s most iconic and eloquent Śaiva devotee.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

See chapter 4 for a further discussion of Nīlakaṇṭha’s ostensive job title and duties at the court of Tirumalai Nāyaka.

[2]:

Known works of Nīlakaṇṭha Dīkṣita include three mahākāvya s (Śivalīlārṇava, Gaṅgāvataraṇa, Mukundavilāsa), a number of laghukāvya s and stotra s (Kalivaḍambana, Sabhārañjana, Anyāpadeśaśataka, Ānandasāgarastava, Vairāgyaśataka, Śāntivilāsa, Gurutattvamālikā), a drama titled the Nalacaritranāṭaka, and one campū (Nīlakaṇṭhavijayacampū).

[3]:

The Mahābhāṣyapradīpaprakāśa is not published, and I have not been able to access a usable manuscript of the work. Two manuscript copies are recorded as being held in the Government Oriental Manuscripts Library in Chennai: a Telugu-script palm leaf manuscript and a Devanāgarī paper transcript. The transcript is currently “missing,” and the palm leaf manuscript is so badly damaged as to be virtually unusable. Another manuscript is said to be located at the Sarasvati Bhavan Library in Varanasi, which I have not been able to consult.

[4]:

See chapter 2 for further discussion of the Saubhāgyacandrātapa and Gīrvāṇendra Sarasvatī, and chapter 3 for the Śivatattvarahasya.

[5]:

This series of ten Nāyaka portrait sculptures, culminating with that of Tirumalai Nāyaka as the most recent of the sequence, have been documented in detail in Branfoot (2001, 2007, 2011). Previous generations of scholarship made use of these portrait sculptures strictly as an aid to documenting the chronology of Nāyaka political history.

[6]:

See for instance Pollock (2001, 2005) and O’Hanlon (2010, 2011).

[7]:

yaṃ bhāṣyaṃ mahad adhyajīgapad ṛṣiḥ śrīcokkanāthādhvarī yo rāmasya ca nīlakaṇṭhamakhinā bāṇastavaṃ kāritaḥ | vyācaṣṭe kila rāmabhadramakhinas tasyāptaśiṣyaḥ kṛtī bhaumīndraṃ sa hi veṅkaṭeśvarakaviḥ yasyāṃ nibaddhaṃ yaśaḥ || Tanjavur Maharaja Serfoji’s Sarasvati Mahal Library, Ms. No. 3827, Veṅkaṭeśvara Kavi, Patañjalicaritravyākhyā, v. 4.

[8]:

sa svāmī mama daivataṃ taditaro nāmnāpi nāmnāyate |

[9]:

As is made evident by the title of Rāmabhadra’s hymn, the Rāmabāṇastava, and indeed by his very name, Rāmabhadra Dīkṣita held a particular fondness for Rāma, his iṣṭadevatā—an affiliation not uncommon among south Indian Śaivas, as, incidentally, was true of Tyāgarāja as well. His choice of personal deity in no way precluded him from participating in Smārta-Śaiva religious circles, which, as we will see in the next chapter, consisted centrally of cultivating a devotional relationship with the Śaṅkarācārya preceptors of the northern Tamil country.

[10]:

These are Tanjavur Maharaja Serfoji’s Sarasvati Mahal Library, Ms. No. 6924 (chapter 9 of the Dinakarabhaṭṭīya) and No. 6862 (chapter 1 of the Śāstramālāvyākhyāna), respectively.

[11]:

Aside from the Tamil chronicles, the Talavaralāṟu and Stāṉikarvaralāṟu, and the versified records of temple renovations (Tiruppaṇivivaram and Tiruppaṇimālai), our earliest “surviving” historical records of Madurai affairs, a collection of Marathi documents originally maintained in the Mackenzie Collection, have been indefinitely misplaced by the Government Oriental Manuscripts Library in Chennai. At the time of my visit in January of 2012, the staff was unable to locate these documents, all contained in a single bound volume.

[12]:

“Stāṉikarvaralāṟu,” pg. 268: ulakuṭaya perumāḷ maṭātipattiyattukku maṭṭum maṉitarkaḷ illaiy eṉṟu colla atai nammuṭaiya kuruvākiya kēcavatīṭcata ayyaravarkaḷukkup paṇṇuvikkiṟom eṉṟu karttākkaḷ muttuvīrappanāyakkar ayyaṉavarkaḷ tiruvākkuppirantatu.

[13]:

Rāghavendra Tīrtha (ca. 1595–1671) served as pontiff of the Śrī Vijayendra Maṭha in Kumbakonam from 1624 to 1671, according to the attestation of his nephew Nārāyaṇācārya in his hagiographical account, the Rāghavendra Vijaya. For further details on his life and works, see B. N. K. Sharma (2000, 479–490).

[14]:

Vādīndra Tīrtha, Guruguṇastava, v. 34: [tantra]śrīnīlakaṇṭhābhidhamakhimaṇinā bhaṭṭatantrānubandhe granthe [y]āvat tvadīye kariṇi guṇavidāropite ‘bhyarhaṇāya | kīrtis te rāghavendra vratisumatimaṇe nūnam anyūnavegād diṅnāgān ārurukṣuḥ svayam api sahasādhāvad aṣṭau digantāt || Some dispute exists regarding the proper reading of the first two syllables, which are often reported as “mantrī,” suggesting that Nīlakaṇṭha held the official title of mantrin under Tirumalai Nāyaka. Filliozat (1967) accepts this reading. Furthermore, the commentator on the Guruguṇastava of Vādīndra Tīrtha preserves the reading “tantraśrī.” Note also that titles such as Dīkṣita and Makhin, which appear in the present verse, were used interchangeably by Smārta Brahmins in the Tamil region during this period.

[15]:

Taylor, ed. and trans., Oriental Historical Manuscripts, 1835, 149–150. intappirakāram nēmukam paṇṇiṉa uṭaṉē aṭacey varuṣam vayyāci mācam—pūrvapaṭcammukkūṟattampaṇṇiṉārkaḷ. Atu mutal vēlaiyaḷa aticākkirataiyāyp piṟaputittam vantu kaṇppārppatiṉālē aticākkiṟataiyāy naṭantutu. Mūṇṇutāka teppakkuḷam veṭṭukuṟapōtu naṭuvilē uttāṟaṇamāy orukeṇapati utaiyamāṉār avaraik kōvilil yeḷuntaruḷappaṇṇi viccārkaḷ vacanta maṇṭapam tūṇ nāṭṭukuṟapōtu yēkapātamūṟtti vāṇicciyirukkuṟa tuṇai naṭappaṭāteṉaṟu cīmaiyil uḷḷa vayiṣiṇavāḷukku caiyavāḷukkum vākkuvātamāy ākumācamvaraikkum vivacāram yēviṉa cuvāmi muṉṉilaikki naṭantutu appāla caivacittānti appātīṭcatā vayiṣṇar ayyātīṭcatāyyaṉavarkaḷ aṉekam kiṟantaṅkaḷp pāttu.

[16]:

The issue of honorifics has also led to some confusion in the genealogy of the Dīkṣitas and other South Indian Brahmin intellectual families. Most genealogical studies refer to a number of individuals within a family simply as “Appa,” “Appayya,” or “Āccān” (Skt. Ācārya), leading to some confusion regarding the numerous “Appayya Dīkṣitas” and “Āccān Dīkṣitas” in Nīlakaṇṭha’s immediate family. Josi (1977), for instance, proposes, based on family history, that Appayya Dīkṣita’s given name was Vināyaka Subrahmaniya. The Ayya Dīkṣita referred to in this passage, being a Vaiṣṇava, is evidently distinct from the one referred to in the Stāṉikarvaralāṟu regarding the Tiruviḷaiyāṭal festivals. Beyond this, we have little basis for conjecturing the identity of these two individuals. Some, such as Mahalinga Sastri, have hypothesized that Appa Dīkṣita here ought to be identical to the famous Appayya Dīkṣita, but this proposal results in insoluble chronological difficulties.

[17]:

Consider, for instance, the Brahmin ministers Madanna and Akkanna of the seventeenth-century Golkonda sultanate in the Deccan, who nearly succeeded in overthrowing the state and personally seizing power. See Kruijtzer (2002) for further discussion. Concerning the spread of Persianate administrative practices prevalent in Golkonda at the time, Kruijtzer notes that the typical bilingual Persian farmān s issued by the brothers were unattested in the far South until eighteenth-century Maratha rule in Tanjavur. During the seventeenth century, neither Mughal nobility nor Maratha Brahmins were visibly present in the Nāyaka kingdoms, nor do we find mention of a class of individuals analogous to the Kāyasthas of North India.

[18]:

Three copper-plate grants survive today testifying to a sustained relationship between the Madurai Nāyaka dynasty and a certain lineage of Brahmins of the Kauṇḍinya Gotra who maintained control of a monastery dedicated to the transgressive Śākta goddess Ekavīrā that was associated with the Jambukeśvara temple in Tiruvanaikka near Srirangam. Preceptors of this lineage appear to have referred to themselves as the Śrīkaṇṭha Ākāśavāsīs. For instance, copper plate 25 of 1937–1938, dated to Śaka 1584, records the following memory of the lineage’s long-standing association with the Madurai Nāyakas: rāyarājamahāma[n]trīśiṣyo nāgappanāyakaḥ | tasyājani sutas so ‘yaṃ viśvanāthākhyanāyakaḥ || svasevāniratasyāsya śiṣyasya vinīta tasya mudānvitaḥ | śrīkaṇṭhākāśaso tatpāṇḍyarājyaṃ dadau kila || labdhvā pañcākṣaraṃ tasmāt śrīkaṇṭhākāśavāsinaḥ | pañcagrāmān dadau tasya viśvanāthākhyanāyakaḥ || (Transcribed in July 2011 from the estampage currently held at the Archaeological Survey of India in Mysore.) The remainder of the grant, dating from Tirumalai Nāyaka’s reign, goes on to detail in Telugu the villages granted to the Śrīkaṇṭha Ākāśavāsi Mahādeva Dīkṣitulu, which enabled the lineage to maintain a presence at a number of prominent Śaiva sites in the Tamil country, such as Jambukeśvara, Mātṛbhūteśvara, Rāmeśvara, and Cokkanāthapuram. In this section, Tirumalai Nāyaka is made to acknowledge his continuing family preceptorial relationship with the lineage: “mā vaṃśaṃ gurusvāmi āyina śrīkaṇṭhākāśavāsi vāri santati kaundinyagotraṃ katyāyina sūtraṃ yajuśākhā sāgni caturmahāvratavājapeyayājī mahādevadikṣitula vāraina mā gurusvāmi vāriki mā vaṃśakarta nāgamanāyadu vāri santati tirumalanāyaḍu vāru.”

No such monastery exists today; the institution in question may have been replaced by the Śaṅkara maṭha now affiliated with the temple. Numerous stone inscriptions in the Jambukeśvara temple attest (all recorded 1937–1938) to the sizable influence of the Ākāśavāsīs over the Jambukeśvara temple, particularly two preceptors known as Mahādeva Dīkṣita and Sadāśiva Dīkṣita. Some even provide intriguing hints of their doctrinal position, such as repeated reference to the “three names of Śiva”: Śiva, Śambhu, and Mahādeva. For instance: śivanāmatrayaṃ śivaśambhu mahādeva... kirttanād [sic] eva gacchati | śivanāmatrayaṃ yas tu sakṛt paṭhati mānavaḥ | mahāpātakānāṃ pāttaiḥ mucyate nātra saṃśayaḥ ||... aṣṭākṣarasvarūpatvāt nnāmatrayam udāhṛtaṃ || śaivaṃ nnāmatrayaṃ loke jayati sma sanātanaṃ | sadāśivamakhindreṇa guruṇā saṃprakāśitaṃ|| (ARE 61 of 1937–1938).

[19]:

In one of his publicly performed dramas, Nīlakaṇṭha’s younger brother Atirātra Yajvan refers to his elder brother as master of the local literary society: “naṭī: kiṃṇu khu ehiṃtuhmāṇa eārisa kouhaṃlākāraṇam (kiṃ nu khalv idānīṃ yuṣmākam etādṛśakautūhalakāraṇam). sūtradhāraḥ: abhigatasabhānāyakalābhaḥ. naṭī: ko ṇu khu eso īdiso (ko nu khalv eṣa īdṛśaḥ.) sūtradhāraḥ: ayaṃ kila bharadvājakulapārāvārapārijātasakalakalāsāmrājyasiṃhāsanādhipatis tatrabhavataḥ śrīmato nārāyaṇādhvariṇas tapaḥparipākaḥ kartā kāvyānāṃ vyākartā tantrāṇām āhartā kratūnāṃ vyāhatā nṛpasabheṣu digantaraviśrāntakīrtir apāramahimā mānavākṛtiḥ sākṣād eva dākṣāyaṇīvallabhaḥ śrīkaṇṭhamatasarvasvavedī śrīnīlakaṇṭhādhvarī.”

[20]:

Our clearest source of information on this issue concerns the feudatory relationship between the Madurai Nāyakas and the emergent Setupati kingdom of Ramnad. Howes (1999) documents that this relationship was established on ritual as well as political grounds through the Śākta worship of Rājarājeśvarī, a statue of whom is said to have been given to the Setupati family by Tirumalai Nāyaka. Soon after, the Navarātri festival was initiated at Ramnad (as recorded in a copper-plate grant dating to 1659). A mural painting from the palace at Ramnad, preserved in the collection of the École française d’Extrême-Orient in Pondicherry, depicts Rājarājeśvarī bestowing the royal scepter upon the Setupati king, a ritual element integral to the royal celebration of Navarātri across South India.

[21]:

See also Bronner (2015) for the memory of Appayya’s identity as an incarnation of Śiva, which seems to have begun to circulate soon after his death.

[22]:

Quoted from a recording made at Nīlakaṇṭha’s ārādhanā in Palamadai, January 2011.

[23]:

sa svāmī mama daivataṃ taditaro nāmnāpi nāmnāyate |