Charaka Samhita and Sushruta Samhita

by Nayana Sharma | 2015 | 139,725 words

This page relates ‘three stages of Surgical procedures’ of the study on the Charaka Samhita and the Sushruta Samhita, both important and authentic Sanskrit texts belonging to Ayurveda: the ancient Indian science of medicine and nature. The text anaylsis its medical and social aspects, and various topics such as diseases and health-care, the physician, their training and specialisation, interaction with society, educational training, etc.

The three stages of Surgical procedures

The course of surgical treatment is divided into three stages- pūrva-karma (pre-operative measures), pradhāna-karma (operative procedures), and paścāt-karma (post-operative care).[1] Gathering of the requisite materials and preparation of the patient constitute the pre-operative stage.

1. The pre-operative stage:

The surgeon is required to have the following instruments and accessories (upayantras) at hand:

- blunt and sharp instruments (yantras and śastras)

- caustics

- fire cautery

- probes (śalākā)

- horn

- leeches

- gourd-a blood sucking apparatus

- jambavaustha –a cauterising instrument

- swab

- gauge

- suturing materials[2] and bandages (paṭṭa)[3]

- leaves

- honey

- ghṛta

- muscle fat (vasā)

- milk

- oil

- nourishing liquids

- decoctions

- ointments

- pastes

- fans for cooling

- cold and hot water

- utensils

- attendants who should be affectionate, steady and strong[4]

- large tub to immerse patients of falls or with injuries to their vital parts.[5]

When suitable iron instruments are not available, the surgeon can resort to substitute materials such as bamboo, quartz, glass, kuravinda,[6] hair, nail and fingers. The first four can be used on infants and others afraid of instruments.[7] The nail is useful in extraction, excision, incision, and any other procedure possible with it. Hair, finger or even sprouts can function as a probe in its absence, while the leaves having sharpness such as those of goji, sephalika and sakapatra (teak tree) help in the drainage of lesions within the oral cavity and the eyelids. Other substitutes for sharp instruments are alkalis, fire cautery, and leeches.[8] The substitute instruments are the anuśastras or the minor instruments.[9]

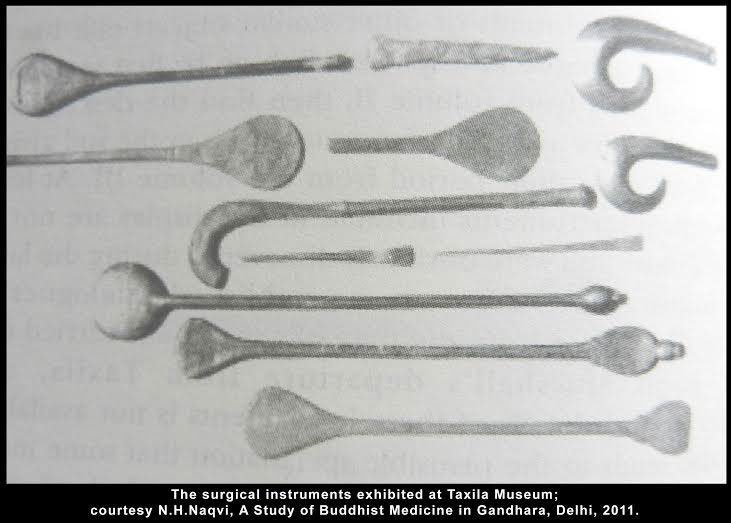

It would be pertinent to point out that the archeological record for medical artefacts, particularly surgical instruments in India, is very poor. In 1858, James Princep had reported the finding of two copper probes for applying antimony in the excavation of Bijnos and Behat.[10] It is only at some sites in Gandhara that a few surgical tools have been discovered which are now displayed at the Taxila Museum. The collection of twelve items made of pure copper includes decapitators, probes (śalākā), spatulae, tongue depressors, forceps, suturing needles, and a few iron scalpels.[11]

Before undertaking the procedure, the surgeon needs to ensure that the patient is strong (balvantam) enough to undergo the operative procedure.[12] The text identifies those patients who are unable to withstand pain or too apprehensive of going under the knife rendering surgical interventions difficult. They include kings, the affluent, children, the elderly, timid (bhīru), weak persons, women, and delicate (sukumāra) individuals.[13] The surgeon is enjoined to adopt special surgical techniques for such patients. The procedure of blood-letting by leeches is preferred for them. The knife is also avoided for excising the sinus in the emaciated, the weak and the timid patient or if it occurs in some vulnerable area, and a caustic thread (kṣāra-sūtra)[14] is used instead.[15]

The preparatory measures for a surgery are clearly delineated by Suśruta. The three stages of a procedure, i.e., the preoperative, the operative and the post-operative phases in modern surgery are also mentioned in the text. First an appropriate day is selected that is astrologically propitious.[16] It may be pointed out that the auspiciousness of the day is not always mentioned in other procedures. Generally, a clear cloudless day is preferred for surgeries[17] in which case the coincidence of a date predetermined on basis of astrological calculations with the desirable weather conditions could not have been always possible. Suitability of the weather is of greater concern in most procedures rather than the auspiciousness of the time; as for instance, the weather should neither be too hot nor too cold during liṅganāśa or cataract surgery.[18] Similarly, it is not possible to abide with astrological predication in traumatic wounds requiring immediate treatment.[19]

Selection of an appropriate place:

A designated operating place not mentioned in the text. A covered and clean place is preferred.[20] Eye surgeries are, however, conducted in rooms protected from the sun and the wind.[21]

Preparatory therapies for the patient:

As a preparatory measure the patient is subject to oleation (snehan) and fomentation (svedana) which appears to be common to practically all surgeries, even in those of the eye.[22] The patient preparing for removal of urinary calculi undergoes oleation, eliminative procedures and weight reducing measures. He is then massaged with oil and fomented.[23] The importance of oleation derives from the notion that the fatty element is the essential constituent of the human body. Prāṇas (vital powers) are believed to be present mainly in the snehas and are thus capable of being attained by application or consumption of oily substances.[24] Oleation is also understood to strengthen the digestive power and the body.[25] Therefore, it acts as a shield that protects the body against incipient stress that surgical processes bring to bear on the physique by way of blood loss, dietary restrictions, etc.

Dietary restrictions:

Just as there are pre-operative dietary restrictions for the patient in present day surgery, Suśruta delineates the same for each type of surgical procedure. The patient of piles is given bland and warm food consisting more of liquids and less of cereals.[26] In certain procedures such as foetal malpresentations, abdominal diseases, piles, urinary calculi, fistula-in-ano, and oral diseases, complete abstention from food is recommended.[27]

Preparation of the surgeon:

The surgeon needs to take care of his personal hygiene, keep his hair short, pare his nails, put on clean apparel and maintain a cheerful appearance.[28]

Performance of auspicious rites:

In some instances, there is mention of ritual worship as part of the pre-operative procedure and offerings to priests who chant auspicious texts, as before operation for drainage of abscess[29] or prior to removal of urinary stones.[30] It is not clear if such rituals were performed before all procedures but it may be mentioned that the operation for urinary stones is considered particularly difficult wherein chances of success are bleak.[31] However in emergency situations when the patient‘s case did not allow elaborate preparations, the surgeon is advised to take immediate remedial measures and dispense with the routine measures as if his own house were on fire.[32] Possibly the implication is that the surgery had to be performed without consultation of astrologers about the auspicious time and moment and the rites and rituals dispensed with.

Consent of the authorities:

The surgeon is advised to take the consent of the king in particularly difficult procedures, such as, removal of urinary stones[33] and management of foetal malpresentations[34] but is not mentioned as mandatory in other cases of surgical interventions.

2. The Operative Procedure

After assessing the condition of the patient, the surgeon is advised to give alcohol for those who are unable to withstand the pain and to those who are accustomed to it.[35] It is the only anesthetic agent mentioned in the treatise. The surgeon needs to be alert to the condition of the patient during the procedure. Cold water is sprinkled over the patient after the incision is made and the surgeon is advised to say some soothing words.[36] If he loses consciousness, the procedure is discontinued and efforts made to revive the patient.[37]

3. Post-Operative Stage

Following the procedure, the patient is reassured and cooled water is sprinkled over him. The immediate concerns of the surgeon are haemostatis (prevention of blood loss), dressing of the wound and application of an appropriate bandage.[38] The subsequent concerns are management of surgery related complications (such as pain) and the prevention of serious complications like suppuration of the wound. To ensure the healing of the wound, the patient is taken to a room for recuperation after the wound is dressed and a suitable bandage is applied.[39] An appropriate dietary regime (āhāra) is also an essential part of the recovery programme of the patient. It is included in the list of sixty procedures for the management of wounds and ulcers.[40] Light, demulscent, warm and appetising diet in small quantities is prescribed in most cases.[41] The patient had to be careful about his diet and movements so as not to cause excessive strain which could delay the healing.[42] The constant observation of the patient by the surgeon in this phase of management is evident from the text.

We may take post-operative management of cataract surgery as a case in point. The text lays emphasis on extreme care of the patient to prevent any irritation or injury to the eye. The patient is placed in a room protected from dust, smoke, wind, sunlight and other natural elements. He is required to lie down supine and avoid belching, coughing, sneezing, spitting and shivering,[43] which implies avoidance of any kind of sharp jerking movements. The bandage is removed every third day, the eye is washed with vāta-allaying decoctions and fomented to avoid the danger of vāta vitiation. Along with other post operative measures and a light diet in moderate quantity is also stipulated for ten days.[44] The surgeon is required to look out for complications arising from technical errors during operation or from negligence on part of the patient of the prescribed regimen. Redness, inflammation, new growths, sucking pain, bubble-like projections, squint, adhimantha (glaucoma), etc., are indicative of complications which have to managed according to the doṣas involved. In order to provide relief from pain and redness in the eye, Suśruta gives eight medicinal recipes. Should the pain persist, the surgeon may take recourse to venepuncture and cauterization.[45] Suśruta further suggests the application of collyriums for improvement of vision.[46] Since the medication is applied by the surgeon, this can be seen as follow up procedure.

Restrictions on physical exertion and diet pertain not only during the course of treatment but are advised for almost a year before resumption of normal activity.[47] Indigestion and excessive emotional states like exhilaration, anger, fear, etc. are considered injurious during recuperation.[48] In fact, Suśruta regards a stable psychological environment no less important in recuperation than medicine. Extreme emotions like jealousy, rage, fear, grief, worry as well as unpleasant scenes and disagreeable words are not conducive to healing. Similarly, keeping awake at night, over indulgence in conversation, physical exercise, standing for a long time or moving about are all proscribed in the text.[49] Anything physically and mentally fatiguing is seen as inhibiting healing. It is said that the patient with a cheerful disposition and optimistic about his recovery will surely recuperate faster by listening to pleasant discourses from the sacred texts.[50]

The recovery chamber is described as well-equipped, neat and clean, spacious, well-ventilated but sheltered from the sun and the wind. It is provided with a comfortable cot, mattress and linen.[51] It should ideally be well planned and built on even ground and in a clean and unpolluted area with the rooms facing the east. It is imperative to keep out excessive draughts, heat, dust, smoke, dew and flies.[52] This suggests that certain measures had to be taken to keep the room protected from pollutants as well as from excessive cold, heat and draughts so that the patient experiences no discomfort. Besides, the patient is advised to be heedful to cleanliness and his personal hygiene by paring his nails, cropping his hair short and putting on white clothes.[53] Performance of propitiatory and auspicious rites to the gods, brāhmaṇas and preceptors is necessary to prevent harm from malicious beings who invade the patient‘s tissues through the wound.[54]

The need for vigilance is also emphasised as a preventive measure to protect the surgical patient from the niśācaras (night rovers).[55] He should be ever watchful and always in the company of people. The room is to be provided with lamps, water, sharp instruments, garlands, strings, flowers, fried paddy (for offerings) etc., while the patient listens to discourses which are pleasing and auspicious so as to ease his mind.[56] Drugs believed to have possible properties of warding off infection are kept on his head.[57] At dawn and dusk, it is recommended that priests and surgeons recite verses from the four Vedas and pronounce other benedictory measures.[58] Prayers are believed to reassure him and relieve his suffering, and may be seen as a palliative measure. Fumigation of the wound with mustard, nīma leaves, ghṛta and salt twice a day[59] and fanning with a whisk are beneficial for this regimen ensures that the malevolent beings flee as hastily as the deer on sighting a lion.[60] Fumigation was essential to relieve the foul odours and to have germicidal action.

The practices of yama and niyama are recommended as additional protective measures (rakṣāvidhāna) for the surgical patient.[61] The constituents of these ascetic practices have been noted in Chapter 8. Significantly, the interpretation of niyama in Suśruta is different from Patañjali‘s precepts which have been accepted by Caraka. The observances of niyama in Yogasūtra are cleanliness or purity (śauca), contentment (santośa), penance (tapas), self-study (svadhāyaya) and devotion to God (īśvarapranidhana). According to Suśruta, however, niyama implies absence of anger (akrodha), service of the preceptor (guruśuśrūṣā), cleanliness (śauca), light diet (āhāralāghavam) and alertness or vigilance (apramāda).[62] The instructions of Suśruta are far more practicable and reasonable keeping the needs of the patient in consideration.

Awareness of the importance of a highly sanitized environment in the recovery room is evident from the text. Cleanliness, comfortable conditions, agreeable ambience, regular waking and sleeping hours, minimal exertion and appropriate diet at regular intervals, in the view of ancient medical science, are optimal for convalescence.[63] Moreover, the need to keep an optimistic attitude about recovery underlines the necessity to have faith in his treatment and his physician.

To attend to the needs of the convalescent and keep him mentally engaged, visits of affectionate friends and companions who are good conversationalists is encouraged. They can console the patient in his pain and help minimize his agony. However, women visitors especially, those for whom the patient may feel sexual attraction, is discouraged.[64] The ancient Indian physicians had a clear understanding of the correlation of psychological well-being and physical health. The attendants who nursed the convalescent were possibly employed by the patient.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

[2]:

The suturing materials are fine thread, bark of aśmantaka (Bauhinia racemosa Linn.), thread of śana (Crotolaria juncea Linn.), silk thread (kṣauma), tendon, hair, fibres of mūrvā and guḍūcī (Tinospora cordifolia); Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 25.20-21. Black ants are also used for suturing; Suśruta Saṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 14.17.

[3]:

Several kinds of materials can be used for this purpose depending on the nature of the wound and the season: flax (kṣauma), cotton (kārpāsa), wool (avika), a kind of cloth (dukūla), silk (kauśeya), a kind of cloth (patrorṇa), Chinese silk (cīnapaṭṭa), leather (carma), inner bark of trees (antarvalkalā), gourd peel (alābusakala), tapes made from creepers (latā) or bamboo strips (vidala), string or cord (rajju) made from muñja grass, cotton seeds (tūlaphala), cream of milk (santānikā), and metals (lauha); Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 18.16.

[4]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 5.6.

[5]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 2.77-78.

[6]:

A kind of barley, the plant Terminalia Catappa; Monier-Williams, p.255.

[7]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 8.15-16.

[8]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 8.17-19/1.

[9]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 8.15.

[10]:

A. Narayanan and S.R. Thrigulla, ‘Tangible Evidence for Surgical Practice in Ancient India’, Journal of Indian Medical Heritage, Vol. XLI, 2011, pp. 1-18.

[12]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 6.4; 7.30.

[13]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 13.11.

[14]:

A thread immersed in caustics.

[15]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 17.29-30.

[16]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 5.7.

[17]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 6.4.

[18]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Uttaratantra 17.57.

[19]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 1.4.

[20]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 6.4.

[21]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Uttaratantra 13.3.

[22]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Uttaratantra 13.3, 10-11.

[23]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 7.30.

[24]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 31.3.

[25]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 31.57.

[26]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 6.4.

[27]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 5.16.

[28]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 10.3.

[29]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 5.7.

[30]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 7.30.

[31]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 7.28.

[32]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 5.40.

[33]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 7.29.

[34]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 15.3.

[35]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 17.11.

[36]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 5.17.

[37]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 7.31-32.

[38]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 5.17.

[39]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 5.17-18.

[40]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 1.8.

[41]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 1.132.

[42]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 19.20.

[43]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Uttaratantra 17.66-68.

[44]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Uttaratantra 17.69-70.

[45]:

S.S. Uttaratantra 17.87-95.

[46]:

S.S. Uttaratantra 17.96-99.

[47]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 6.22.; 7.35; 8.54.

[48]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 5.36-39

[49]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 19.20.

[50]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 19.26.

[51]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 19.3-5.

[52]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 19.20.

[53]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 19.23.

[54]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 19.23.

[55]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Uttaratantra 60.3.

[56]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 19.25.

[57]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 19.29.

[58]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 19.27.

[59]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 19.28.

[60]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 19.30- 31.

[61]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 1.133.

[62]:

Ḍalhaṇa on Suśruta Saṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna 1.133.

[63]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 19.20.

[64]:

Suśruta Saṃhitā Sūtrasthāna 19.7-15.