Satapatha-brahmana

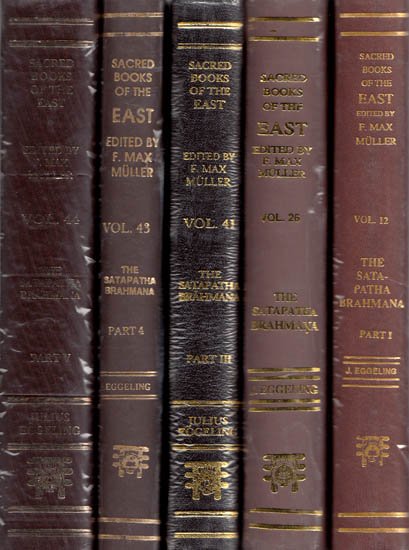

by Julius Eggeling | 1882 | 730,838 words | ISBN-13: 9788120801134

This is Satapatha Brahmana VIII.1.4 English translation of the Sanskrit text, including a glossary of technical terms. This book defines instructions on Vedic rituals and explains the legends behind them. The four Vedas are the highest authortity of the Hindu lifestyle revolving around four castes (viz., Brahmana, Ksatriya, Vaishya and Shudra). Satapatha (also, Śatapatha, shatapatha) translates to “hundred paths”. This page contains the text of the 4th brahmana of kanda VIII, adhyaya 1.

Kanda VIII, adhyaya 1, brahmana 4

[Sanskrit text for this chapter is available]

1. Now some lay down (these bricks) so as to be in contact with the (gold) man, for he is the vital air, and him these (bricks) sustain; and because they sustain (bhṛ) the vital air (prāṇa), therefore they are called 'Prāṇabhṛtaḥ.' Let him not do so: the vital air is indeed the same as that gold man, but this body of his extends to as far here as this fire (altar) has been marked out. Hence to whatever limb of his these (breath-holders) were not to reach, that limb of his the vital air would not reach; and, to be sure, to whatever limb the vital air does not reach, that either dries up or withers away: let him therefore lay down these (bricks) so as to be in contact with the enclosing stones; and by those which he lays down in the middle this body of his is filled up, and they at least are not separated from him.

2. Here now they say, 'Whereas in (the formulas) "This one, in front, the existent--this one, on the right, the all-worker--this one, behind, the all-embracer--this, on the left, heaven--this one, above, the mind"--they (these bricks) are defined as exactly opposite the quarters, why, then, does he lay down these (bricks) in sidelong places[1]?' Well, the Prāṇabhṛtaḥ are the vital airs; and if he were to place them exactly opposite the quarters, then this breath would only pass forward and backward; but inasmuch as he now lays down these (bricks) thus defined in sidelong places, therefore this breath, whilst being a backward and forward one, passes sideways along all the limbs and the whole body.

3. Now that Agni (the altar) is an animal, and (as such) he is even now made up whole and entire,--those (bricks) which he lays down in front are his fore-feet, and those behind are his thighs; and those which he places in the middle are that body of his. He places these in the region of the two retaḥsic (bricks), for the retaḥsic are the ribs, and the ribs are the middle, and that body is in the middle (of the limbs). He places them all round, for that body extends all round.

4. Here now they say, 'Whereas in the first (four) sets he lays down a single stoma and a single pṛṣṭha each time, why, then, does he lay down here (in the centre) two stomas and two pṛṣṭhas?' Well, this (central set) is his (Agni's) body: he thus makes the body (trunk) the best, the largest, the most vigorous of limbs[2]; whence that body is the best, the largest, and most vigorous of limbs.

5. Here now they say, 'How does that Agni of his become made up whole and entire in brick after brick?'--Well, the formula is the marrow, the brick the bone, the settling the flesh, the sūdadohas the skins, the formula of the purīṣa (fillings of earth) the hair, and the purīṣa the food: and thus indeed that Agni of his becomes made up whole and entire in brick after brick.

6. That Agni is possessed of all vital power: verily, whosoever knows that Agni to be possessed of all vital power (āyus), attains his full measure of life (āyus).

7. Now, then, as to the contraction and expansion (of the body). Now some cause the built (altar) in this way[3] to be possessed of (the power of) contraction and expansion: that Agni indeed is an animal;

and when an animal contracts and expands its limbs, it develops strength by them.

8. [Vāj. S. XXVII, 45] 'Thou art Saṃvatsara,--thou art Parivatsara,--thou art Idāvatsara,--thou art Idvatsara,--thou art Vatsara,--May thy dawns prosper[4]!--may thy days and nights prosper!--may thy half-months prosper!--may thy months prosper!--may thy seasons prosper!--may thy year prosper!--For going and coming contract and expand thyself!--Of Eagle-build thou art: by that deity, Aṅgiras-like, lie thou steady[5]!'

9. Śāṭyāyani also once said, 'Some one heard (the sound)[6] of the cracking wings of the (altar)-when touched with this (formula): let him therefore by all means touch it therewith!'

10. And Svarjit Nāgnajita or Nagnajit, the Gāndhāra, once said, 'Contraction and expansion surely are the breath, for in whatever part of the body there is breath that it both contracts and expands; let him breathe upon it from outside when completely built: he thereby lays breath, the (power of) contraction and expansion, into it, and so it contracts and expands.' But indeed what he there said as to that contraction and expansion, it was only one of the princely order who said it; and assuredly were they to breathe upon it from outside a hundred times, or a thousand times, they could not lay breath into it. Whatever breath there is in the (main) body that alone is the breath: hence when he lays down the Prāṇabhṛtaḥ (breath-holders), he thereby lays breath, the (power of) contraction and expansion, into it; and so it contracts and expands. He then lays down two Lokampṛṇā (bricks) in that corner[7]: the meaning of them (will be explained) further on[8]. He throws loose earth (on the layer): the meaning of this (will be explained) further on[9].

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

That is to say, why does he not place them at the ends of the spines, but at the corners of the (square) body, i.e. in places intermediate between the lines running in the direction of the points of the compass? When speaking of the regions, or quarters, it should be borne in mind that they also include a fifth direction, viz. the perpendicular or vertical line (both upward and downward) at any given point of the plane.

[2]:

Or,--better, larger, and more vigorous than the limbs.

[3]:

Viz. by touching, or stroking along, the layer of the altar, and muttering the subsequent formulas.

[4]:

Or, perhaps, 'may the dawns chime in (fit in) with thee!'

[5]:

For this last part of the formula ('by that deity,' &c.), the so-called settling-formula, see part iii, p. 307, note 1.

[6]:

Harisvāmin (Ind. Off. MS. 657) seems to supply 'śabdam;' the sound of the cracking being taken as a sign of the powerful effect of the formula. Unfortunately, however, the MS. of the commentary is hopelessly incorrect.

[7]:

Viz. in the south-east corner, or on the right shoulder, of the altar. From these two lokampṛṇās (or space-fillers) he starts filling up, in two turns, the still available spaces of the 'body' of the altar, as also the whole of the two wings and the tail. For other particulars as to the way in which these are laid down, see VIII, 7, 2, 1 seqq. The 'body' of an ordinary altar requires in this layer 1028 lokampṛṇās of three different kinds, viz. a foot (Ind.), half a foot, and a quarter of a foot square, occupying together a space of 321 square feet, whilst the 98 special (yajushmatī) bricks fill up a space of 79 square feet. Each wing requires 309 lokampṛṇās of together 120 square feet; whilst the tail takes 283 such bricks, of together 110 square feet. The total number of lokampṛṇās in the layer thus amounts to 7929 of all sizes, equal to 671 square feet. If (as is done in Kāty. Śrautas. XVII, 7, 21) the 21 bricks of the Gārhapatya (part iii, p. 304) are added to this number, the total number of lokampṛṇās is 1,950. Similarly, in the second, third, and fourth layers; whilst the last layer requires about a thousand lokampṛṇās more than any of the others, viz. 2,922, or, including the special hearths, 3,000. The total number of such bricks required--including the 21 of the Gārhapatya--amounts to 10,800. Cp. Weber, Ind. Stud. XIII, p. 255.

[8]:

See VIII, 7, 2, 1 seq.

[9]:

See VIII, 7, 3, 1 seq.