Satapatha-brahmana

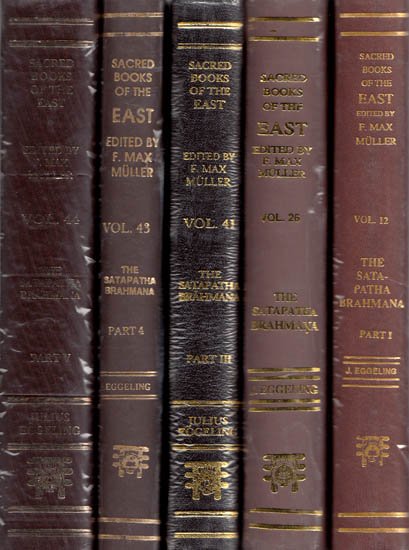

by Julius Eggeling | 1882 | 730,838 words | ISBN-13: 9788120801134

The English translation of the Satapatha Brahmana, including annotations and footnotes. The Sanskrit brahmanas are commentaries on the Vedas, detailling the vedic rituals and various legends. The text contains details on altar-constructions, mantra recitation and various other topics. The Satapatha-brahmana dates to at least the first millenium B...

Introduction to volume 3 (kāṇḍa 5-7)

THE first of the three Kāṇḍas contained in the present volume continues the dogmatic discussion of the different forms of Soma-sacrifice, in connection with which two important ceremonies, the Vājapeya and Rājasūya, are considered. From a ritualistic point of view, there is a radical difference between these two ceremonies. The Rājasūya, or 'inauguration of a king,' strictly speaking, is not a Soma-sacrifice, but rather a complex religious ceremony which includes, amongst other rites, the performance of a number of Soma-sacrifices of different kinds. The Vājapeya, or 'drink of strength' (or, perhaps, 'the race-cup'), on the other hand, is recognised as one of the different forms (saṃsthā) which a single Soma-sacrifice may take. As a matter of fact, however, this form hardly ever occurs, as most of the others constantly do, in connection with, and as a constituent element of, other ceremonies, but is almost exclusively performed as an independent sacrifice. The reason why this sacrifice has received a special treatment in the Brāhmaṇa, between the Agniṣṭoma and the Rājasūya, doubtless is that, unlike the other forms of Soma-sacrifice, it has some striking features of its own which stamp it, like the Rājasūya, as a political ceremony. According to certain ritualistic authorities[1], indeed, the performance of the Vājapeya should be arranged in much the same way as that of the Rājasūya; that is, just as the central ceremony of the Rājasūya, viz. the Abhishecanīya or consecration, is preceded and followed by certain other Soma-days, so the Vājapeya should be preceded and followed by exactly corresponding ceremonies.

The preceding Kāṇḍa was chiefly taken up with a detailed discussion of the simplest form of a complete Soma-sacrifice, the Agniṣṭoma, serving as the model for all other kinds of one-day (ekāha) Soma-sacrifices; and it also adverted incidentally to some of the special features of such of the remaining fundamental forms of Soma-sacrifice as are required for the performance of sacrificial periods of from two to twelve pressing-days--the so-called ahīna-sacrifices--as well as for the performance of the sacrificial sessions (sattra) lasting from twelve days upwards. As the discussion of the Vājapeya presupposes a knowledge of several of those fundamental forms of Soma-sacrifice, it may not be out of place here briefly to recapitulate their characteristic features.

The ekāha, or 'one-day' sacrifices, arc those Soma-sacrifices which have a single pressing-day, consisting of three services (or pressings, savana)--the morning, midday, and third (or evening) services--at each of which certain cups of Soma-liquor are drawn, destined to be ultimately consumed by the priests and sacrificer, after libations to the respective deities have been duly made therefrom. At certain stated times during the performance, hymns (stotra) are chanted by the Udgātṛs; each of which is followed by an appropriate recitation (śastra) of Vedic hymns or detached verses, by the Hotṛ priest or one of his assistants. An integral part of each Soma-sacrifice, moreover, is the animal sacrifice (paśubandhu); the number of victims varying according to the particular form of sacrifice adopted. In the exposition of the Agniṣṭoma, the animal offering actually described (part ii, p. 162, seq.) is that of a he-goat to Agni and Soma, intended to serve as the model for all other animal sacrifices. This description is inserted in the Brāhmaṇa among the ceremonies of the day preceding the Soma-day, the animal offering to Agni-Soma being indeed a constant feature of that day's proceedings at every Soma-sacrifice; whilst the slaughter of the special victim, or victims, of the respective sacrifice takes place during the morning service, and the meat-oblations are made during the evening service of the pressing-day. The ritualistic works enumerate a considerable number of 'one-day' sacrifices, all of them with special features of their own; most of these sacrifices are, however, merely modifications of one or other of the fundamental forms of ekāhas. Of such forms or saṃsthās--literally, 'completions,' being so called because the final chants or ceremonies are their most characteristic features--the ritual system recognises seven, viz. the Agniṣṭoma. Atyagniṣṭoma. Ukthya, Ṣoḍaśin, Vājapeya[2], Atirātra, and Aptoryāma.

The Agniṣṭoma, the simplest and most common form of Soma-sacrifice, requires the immolation of a single victim, a he-goat to Agni; and the chanting of twelve stotras, viz. the Bahish-pavamāna and four Ājya-stotras at the morning service; the Mādhyandina-pavamāna and four Pṛṣṭha-stotras at the midday service; and the Tṛtīya (or Ārbhava)-pavamāna and the Agniṣṭoma-sāman at the evening service. It is this last-named chant, then, that gives its name to this sacrifice which, indeed, is often explained as the 'Agniṣṭoma-saṃsthaḥ kratuḥ[3],' or the sacrifice concluding with 'Agni's praise.' The term 'sāman,' in its narrow technical sense, means a choral melody, a hymn-tune, without reference to the words set thereto. Not unfrequently, however, it has to be taken in the wider sense of a chanted verse or hymn (triplet), a chorale; but, though the distinction is evidently of some importance for the ritual, it is not always easy to determine the particular sense in which the term is meant to be applied, viz. whether a specified sāman is intended to include the original text set to the respective tune, or whether some other verses to which that tune has been adapted are intended. In the case of the Agniṣṭoma-sāman, however, the word 'sāman' cannot be taken in its narrow acceptation, but the term has to be understood in the sense of 'a hymn chanted in praise of Agni.' The words commonly used for this chant, are the first two verses of Rig-veda S. VI, 48, a hymn indeed admirably adapted for the purpose of singing Agni's praises. For the first verse, beginning 'yajñā-yajñā vo agnaye,' the chief tune-book, the Grāmageya-gāna, has preserved four different tunes, all of which are ascribed to the Ṛṣi Bharadvāja: one of them has, however, come to be generally accepted as the Yajñāyajñīya-tune κατ᾽ ἐξοχήν, and has been made use of for this and numerous other triplets[4]; whilst the other tunes seem to have met with little favour, not one of them being represented in the triplets arranged for chanting in stotras, as given in the Ūha and Uhya-gānas. Neither the Yajñāyajñīya-tune, nor its original text, is however a fixed item in the chanting of the Agniṣṭoma-sāman. Thus, for the first two verses of Rig-veda VI, 48, the Vājapeya-sacrifice[5] substitutes verses nine and ten of the same hymn, and these are chanted, not to the Yajñāyajñīya, but to the Vāravantīya-tune, originally composed for, and named after, Rig-veda I, 27, 1 (S. V. I, 17; ed. Calc. I, p. 121) 'aśvaṃ na tvā vāravantam.'

The Ukthya-sacrifice requires the slaughtering of a second victim, a he-goat to Indra and Agni; and to the twelve chants of the Agniṣṭoma it adds three more, the so-called Uktha-stotras, each of which is again followed by an Uktha-śastra recited by one of the Hotrakas, or assistants of the Hotṛ. As the evening service of the Agniṣṭoma had only two śastras, both recited by the Hotṛ, the addition of the three śastras of the Hotrakas would, in this respect, equalize the evening to the morning and midday savanas. The word 'uktha' is explained by later lexicographers either as a synonym of 'sāman,' or as a kind of sāman[6]; but it is not unlikely that that meaning of the word was directly derived from this, the most common, use of the word in the term 'uktha-stotra.' The etymology of the word[7], at all events, would point to the meaning 'verse, hymn,' rather than to that of 'tune' or 'chant;' but, be that as it may, the word is certainly used in the former sense in the term 'mahad-uktha,' the name of the 'great recitation' of a thousand bṛhatī verses[8], being the Hotṛ's śastra in response to the Mahāvrata-stotra at the last but one day of the Gavām-ayana. And, besides, at the Agniṣṭoma a special 'ukthya' cup of Soma-juice is drawn both at the morning and midday pressings, but not at the evening savana. This cup, which is eventually shared by the three principal Hotrakas between them, is evidently intended as their reward for the recitation of their 'ukthas.' At the Ukthya-sacrifice, as might have been expected, the same cup is likewise drawn at the evening service. Though it may be taken for granted, therefore, that 'uktha' was an older term for 'śastra,' it still seems somewhat strange that this terns should have been applied specially to the additional śastras and stotras of the Ukthya-sacrifice. Could it be that the name of the additional Ukthya-cup, as a distinctive feature of this sacrifice, suggested the name for the śastras and stotras with which that cup was connected, or have we rather to look for some such reason as Ait. Br. VI, 13 might seem to indicate? This passage contains a discussion regarding the different status of the Hotrakas who have ukthas of their own, and those who have not; and it then proceeds to consider the difference that exists between the two first and the third savanas of the Agniṣṭoma in respect of the Hotrakas’ ukthas. It is clear that here also, the term 'uktha' can hardly be taken otherwise than as referring to the śastras--though, no doubt, the stotra is sometimes said to belong to the priest who recites the śastra in response to it--and this paragraph of the Brāhmaṇa reads almost like the echo of an old discussion as to whether or not there should be recitations for the Hotrakas at the evening service of a complete Soma-sacrifice. If, in this way, the question of uktha or no uktha had become a sort of catchword for ritualistic controversy, one could understand how the term came ultimately to be applied to the three additional stotras and śastras.

Not unfrequently, the Ukthya is treated merely as a redundant Agniṣṭoma, as an 'Agniṣṭomaḥ sokthaḥ,' or Agniṣṭoma with the Ukthas[9]. Considering, however, that the term Agniṣṭoma, properly speaking, belongs only to a Soma-sacrifice which ends with the Agniṣṭoma (sāman), and that the addition of the Uktha-stotras also involves considerable modifications in the form of most of the preceding chants, a new term such as Ukthya, based on the completing and characteristic chants of this form of sacrifice, was decidedly more convenient. In regard to the composition of the preceding stotras, with the exception of the Mādhyandina-pavamāna and the Agniṣṭoma-sāman, the Ukthya, indeed, may be said to constitute a parallel form of Sacrifice beside the Agniṣṭoma[10], the succeeding saṃsthās following the model of either the one or the other of these two parallel forms.

The Ṣoḍaśin-sacrifice requires, as a third victim, the immolation of a ram to Indra; and one additional chant, the ṣoḍaśi-stotra, with its attendant śastra and Soma-cup. The most natural explanation of the name is the one supplied, in the first place, by Ait. Br. IV, 1 (as interpreted by Sāyaṇa)--viz. the sacrifice which has sixteen, or a sixteenth, stotra[11]. But, as the name applies not only to the sacrifice but also to the stotra and śastra, the Brāhmaṇa further justifies the name by the peculiar composition of the ṣoḍaśi-śastra in which the number sixteen prevails[12]. Very probably, however, the name may have belonged to the sacrifice long before the śastra, for symbolic reasons, had assumed the peculiar form it now presents.

In this summary of the characteristic features of the forms of Soma-sacrifice presupposed by the Vājapeya, no mention has yet been made of the Atyagniṣṭoma, or redundant Agniṣṭoma, which usually occupies the second place in the list of saṃsthās. This form of sacrifice is indeed very little used, and there can be little doubt that it was introduced into the system, as Professor Weber suggests, merely for the sake of bringing up the Soma-saṃsthās to the sacred number of seven. This sacrifice is obtained by the addition of the ṣoḍaśi-stotra to the twelve chants of the Agniṣṭoma, as well as of the special Soma-cup and sacrificial victim for Indra, connected with that chant. It may thus be considered as a short form of the Ṣoḍaśin-sacrifice (though without the full complement of stotras implied in that name), which might have suited the views of such ritualists as held the śastras of the Hotrakas at the evening service to be superfluous[13].

The distinctive feature of the Atirātra-sacrifice, as the name itself indicates, is an 'overnight' performance of chants and recitations, consisting of three rounds of four stotras and śastras each. At the end of each round (paryāya) libations are offered, followed by the inevitable potations of Soma-liquor. That the performance, indeed, partook largely of the character of a regular nocturnal carousal, may be gathered from the fact, specially mentioned in the Aitareya Brāhmaṇa, that each of the Hotṛ's offering-formulas is to contain the three words--'andhas,' Soma-plant (or liquor), 'pā,' to drink, and 'mada,' intoxication. Accordingly, one of the formulas used is Rig-veda II, 19, 1 apāyy asyā'ndhaso madāya, 'there has been drunk (by Indra, or by us) of this juice for intoxication.' The twelve stotras, each of which is chanted to a different tune, are followed up, at daybreak, by the Sandhi-stotra, or twilight-chant, consisting of six verses (Sāma-veda S. II, 99-104) chanted to the Rathantara-tune. This chant is succeeded by the Hotṛ's recitation of the Āśvina-śastra, a modification of the ordinary 'prātar-anuvāka,' or morning-litany, by which the pressing-day of a Soma-sacrifice is ushered in[14]. The Atirātra also requires a special victim, viz. a he-goat offered to Sarasvatī, the goddess of speech. As regards the ceremonies preceding the night-performance, there is again a difference of opinion among ritualists as to whether the ṣoḍaśi-stotra, with its attendant rites, is, or is not, a necessary element of the Atirātra[15]. Some authorities[16], accordingly, distinctly recognise two different kinds of Atirātra,--one with, and the other without, the Ṣoḍaśin. In Kātyāyana's Sūtra, there is no allusion to any difference of opinion on this point, but, in specifying the victims required at the different Soma-sacrifices, he merely remarks (IX, 8, 5) that, 'At the Atirātra there is a fourth victim to Sarasvatī.' This would certainly seem to imply that there are also to be the three preceding victims, including the one to Indra peculiar to the Ṣoḍaśin. Āśvalāyana (V, 11, 1) also refers incidentally to the Ṣoḍaśin as part of the Atirātra, though it is not quite clear from the text of the sūtra whether it is meant to be a necessary or only an optional feature of that sacrifice. The Aitareya Brāhmaṇa (IV, 6), on the other hand, in treating of the Atirātra, enters on a discussion with the view of showing that the night-performance of that sacrifice is in every respect equal to the preceding day-performance; and accordingly, as the three services of the day-performance include fifteen chants and recitations (viz. the twelve of the Agniṣṭoma, and the three Ukthas), so, during the night, the three rounds of in all twelve stotras, together with the sandhi-stotra, here counted as three stotras (triplets), make up the requisite fifteen chants. This Brāhmaṇa, then, does not recognise the Ṣoḍaśin as part of the Atirātra, and, indeed, the manuals of the Atirātra chants which I have consulted make no mention of the ṣoḍaśi-stotra, though it is distinctly mentioned there among the chants of the Vājapeya and the Aptoryāma. The passage in the Aitareya, just referred to, also seems to raise the question as to whether the Atirātra is really an ekāha, or whether it is not rather an ahīna-sacrifice. On this point also the authorities seem to differ; whilst most writers take the Atirātra. and the analogous Aptoryāma, to be 'one-day' sacrifices, the Tāṇḍya Brāhmaṇa (XX) and Lāṭy. IX, 5, 6 class them along with the Ahīnas[17]; and they may indeed be regarded as intermediate links between the two classes of Soma-sacrifice, inasmuch as, in a continued sacrificial performance, the final recitations of these sacrifices take the place of the opening ceremony of the next day's performance. Such, for instance, is the case in the performance of the Atirātra as the opening day of the Dvādaśāha, or twelve days’ period of sacrifice; whilst in the performance of the twelfth and concluding day, which is likewise an Atirātra, the concluding ceremonies of the latter might be considered in a manner superabundant. It is probably in this sense that Lāṭy. (IX, 5, 4) calls the overnight performance of the last day of an ahīna (e. g. the Dvādaśāha) the yajñapuccha, or tail of the sacrifice, which is to fall beyond the month for which, from the time of the initiation, the ahīna is to last.

The Aptoryāma-sacrifice represents an amplified form of the Atirātra. It requires the ṣoḍaśi-stotra and the ceremonies connected with it as a necessary element of its performance; whilst its distinctive feature consists in four additional (atirikta-) stotras and śastras, chanted and recited after the Āśvina-śastra, the concluding recitation of the Atirātra. These four chants are arranged in such a manner that each successive stotra is chanted to a different tune, and in a more advanced form of composition, from the trivṛt (nine-versed) up to the ekaviṃśa (twenty-one-versed) stoma. In the liturgical manuals, the Aptoryāma, moreover, performs the function of serving as the model for a sacrificial performance with all the 'pṛṣṭhas[18].' Though this mode of chanting has been repeatedly referred to in the translation and notes, a few additional remarks on this subject may not be out of place here. When performed in its 'pṛṣṭha' form, the stotra is so arranged that a certain sāman (or chanted triplet) is enclosed, as the 'garbha' (embryo), within some other sāman which, as its 'pṛṣṭha' (i.e. back, or flanks), is chanted a number of times before and after the verses of the central sāman. The tunes most commonly used for forming the enclosing sāmans of a Pṛṣṭha-stotra are the Rathantara and Bṛhat; and along with these, four others are singled out to make up the six Pṛṣṭha-sāmans κατ᾽ ἐξοχήν, viz. the Vairūpa (with the text Sāma-veda II, 212-13), Vairāja (II, 277-9), Śākvara[19] (chanted on the Mahānāmnī verses, Aitar. Ār. IV), and Raivata[20] sāmans., These six sāmans are employed during the six days’ sacrificial period called Pṛṣṭhya-ṣaḍaha, in such a way that one of them, in the order in which they are here enumerated, is used for the first, or Hotṛ's, Pṛṣṭha-stotra on the successive days of that period. In that case, however, these stotras are not performed in the proper 'pṛṣṭha' form[21], i.e. they have no other sāman inserted within them, but they are treated like any other triplet according to the particular stoma, or mode of composition, prescribed for them. But, on the other hand, in the Aptoryāma, when performed 'with all the Pṛṣṭhas,' not only are a number of stotras chanted in the proper 'pṛṣṭha' form, but the 'pṛṣṭha' element asserts itself in yet another way, viz. by the appearance of all the six 'Pṛṣṭha-sāmans' in the course of the performance of the different stotras, in this way:--the Rathantara-tune forms the middlemost of the seven triplets of which the Madhyandina-pavamāna is composed; the Bṛhat forms the 'garbha,' or enclosed sāman, of the Agniṣṭoma-sāman[22]; the Vairūpa the garbha of the third, the Vairāja that of the first, the Śākvara that of the second, and the Raivata that of the fourth, Pṛṣṭha-stotra. It is doubtless this feature which gives to certain Soma-days the name of 'sarvapṛṣṭha,' or one performed with all the (six) Pṛṣṭhas. Then, as regards the particular stotras that are chanted in the proper 'pṛṣṭha' form, these include not only the four so-called Pṛṣṭha-stotras of the midday service, but also the four Āgya-stotras of the morning service, as well as the Agniṣṭoma-sāman and the three Uktha-stotras of the evening service,--in short, all the first fifteen stotras with the exception of the three Pavamāna-stotras. Of the stotras which succeed the Ukthas, on the other hand--viz. the Ṣoḍaśin, the twelve chants of the three night-rounds, the Sandhi-stotra, and the four Atirikta-stotras--not one is performed in the 'pṛṣṭha' form. How often the several verses of the 'pṛṣṭha-sāman,' and those of the 'garbha' are to be chanted, of course depends, in each case, not only on the particular stoma which has to be performed, but also on the particular mode (viṣṭuti) prescribed, or selected, for the stoma. Thus, while all the four Āgya-stotras are chanted in the pañcadaśa, or fifteen-versed-stoma; the four Pṛṣṭha-stotras are to be performed in the ekaviṃśa (of twenty-one verses), the caturviṃśa (of twenty-four verses), the catuścatvāriṃśa (of forty-four verses), and the aṣṭācatvāriṃśa (of forty-eight verses) respectively. Now whenever, as in the case of the pañcadaśa and the ekaviṃśa-stomas, the number of verses is divisible by three, one third of the total number of verses is usually assigned to each of the three parts of the stotra, and distributed over the respective (three or sometimes four) verses of that sāman[23]

To illustrate this tripartite composition, the Hotṛ's Pṛṣṭha-stotra, performed in the twenty-one-versed stoma. may be taken as an example. For the 'pṛṣṭha,' the manuals give the Bṛhat-sāman, on its original text (Sāma-veda II, 159,160, 'tvām id dhi havāmahe,' arranged so as to form three verses), though the Rathantara may be used instead[24]. For the 'garbha,' or enclosed sāman, on the other hand, the Vairāja-sāman (with its original text, S. V. II, 277-9, 'pibā somam indra mandatu tvā') is to be used, a most elaborate tune[25], with long sets of stobhas, or musical ejaculations, inserted in the text. Of the twenty-one verses, of which the stoma consists, seven verses would thus fall to the share of the 'garbha,' and seven verses to that of the pṛṣṭha,' as chanted before and after the 'garbha.' Thus, in accordance with the formula set forth in p. xxii, note 2, the three verses (a, b, c) of the Bṛhat would be chanted in the form aaa-bbb-c; then the verses of the Vairāja-sāman (as 'garbha') in the form a-bbb-ccc; and finally again the Bṛhat in the form aaa-b-ccc. Stotras, the total number of verses of which is not divisible by three, of course require a slightly different distribution. Thus, of the third Pṛṣṭha-stotra, the stoma of which consists of forty-four verses, the two parts of the 'pṛṣṭha' obtain fifteen verses each, whilst the 'garbha' has only fourteen verses for its share.

The Vājapeya, the last of the seven forms of a complete Soma-sacrifice, occupies an independent position beside the Atirātra and Aptoryāma, whose special features it does not share. Like them, it starts from the Ṣoḍaśin, to the characteristic (sixteenth) chant (and recitation) of which it acids one more stotra, the Vājapeya-sāman, chanted to the Bṛhat-tune, in the Saptadaśa (seventeen-versed) stoma, and followed by the recitation of the Vājapeya-śastra. The Saptadaśa-stoma, indeed, is so characteristic of this sacrifice that--as has been set forth at p. 8 note below--all the preceding chants, from the Bahiṣpavamāna onward, are remodelled in accordance with it. Besides, over and above the three victims of the Ṣoḍaśin-sacrifice, the Vājapeya requires, not only a fourth one, sacred to Sarasvatī, the goddess of speech, but also a set of seventeen victims for Prajāpati, the god of creatures and procreation. As regards other rites peculiar to the Vājapeya, the most interesting, doubtless, is the chariot-race in which the sacrificer, who must be either of the royal or of the priestly order, is allowed to carry off the palm, and from which this sacrifice perhaps derives its name. Professor Hillebrandt[26], indeed, would claim for this feature of the sacrifice the character of a relic of an old national festival, a kind of Indian Olympic games; and though there is perhaps hardly sufficient evidence to bear out this conjecture, it cannot at least be denied that this feature has a certain popular look about it.

Somewhat peculiar are the relations between the Vājapeya and the Rājasūya on the one hand, and between the Vājapeya and the Bṛhaspatisava on the other. In the first chapter of the fifth book, the author of this part of our Brāhmaṇa is at some pains to impress the fact that the Vājapeya is a ceremony of superior value and import to the Rājasūya; and hence Kātyāyana (XV, 1, 1-2) has two rules to the effect that the Rājasūya may be performed by a king who has not yet performed the Vājapeya. These authorities would thus seem to consider the drinking of the Vājapeya-cup a more than sufficient equivalent for the Rājasūya, or inauguration of a king; they do not, however, say that the Rājasūya must be performed prior to the Vājapeya, but only maintain that the Vājapeya cannot be performed after the Rājasūya. The Rājasūya, according to the Brāhmaṇa, confers on the sacrificer royal dignity (rājya), and the Vājapeya paramount sovereignty (sāmrājya). It might almost seem as if the relatively loose positions here assigned to the Rājasūya were entirely owing to the fact that it is a purely Kṣatriya ceremony to which the Brāhmaṇa has no right, whilst the Vājapeya may be performed by Brāhmaṇas as well as Kṣatriyas. But on whatever grounds this appreciation of the two ceremonies may be based, it certainly goes right in the face of the rule laid down by Āśvalāyana (IX, 9, 19) that, 'after performing the Vājapeya, a king may perform the Rājasūya, and a Brāhmaṇa the Bṛhaspatisava.' With this rule would seem to accord the relative value assigned to the two ceremonies in the Taittirīya Saṃhitā (V, 6, 2, 1) and Brāhmaṇa (II, 7, 6, 1), according to which the Vājapeya is a 'samrāṭsava,' or consecration to the dignity of a paramount sovereign, while the Rājasūya is called a 'varuṇasava,' i.e., according to Sāyaṇa, a consecration to the universal sway wielded by Varuṇa[27]. In much the same sense we have doubtless to understand the rule in which Lāṭyāyana defines the object of the Vājapeya (VIII, 11, 1), viz. 'Whomsoever the Brāhmaṇas and kings (or nobles) may place at their head, let him perform the Vājapeya.' All these authorities, with the exception of the Śatapatha-Brāhmaṇa and Kātyāyana, are thus agreed in making the Vājapeya a preliminary ceremony, performed by a Brāhmaṇa who is raised to the dignity of a Purohita, or head-priest (so to speak, a minister of worship, and court-priest), or by a king who is elected paramount sovereign by a number of petty rājas; this sacrifice being in due time followed by the respective installation and consecration ceremony, viz. the Bṛhaspatisava, in the case of the Purohita; and the Rājasūya, in that of the king. In regard to the Bṛhaspatisava, which these authorities place on an equality with the Rājasūya, our Brāhmaṇa finds itself in a somewhat awkward position, and it gets out of its difficulty (V, 2, 1, 19) by simply identifying the Bṛhaspatisava with the Vājapeya, and making the Vājapeya itself to be 'the consecration of Bṛhaspati;' and Kātyāyana (XIV, 1, 2) compromises matters by combining the two ceremonies in this way that he who performs the Vājapeya is to perform the Bṛhaspatisava for a fortnight before and after the Vājapeya.

The Rājasūya, or inauguration of a king, is a complex ceremony which, according to the Śrauta-sūtras, consists of a long succession of sacrificial performances, spread over a period of upwards of two years. It includes seven distinct Soma-sacrifices, viz. 1, the Pavitra, an Agniṣṭoma serving as the opening sacrifice, and followed, after an interval of a year (during which the seasonal sacrifices have to be performed), by 2, the Abhishecanīya, an Ukthya-sacrifice, being the consecration (or anointing) ceremony. Then follows 3, the Daśapeya, or 'drink of ten,' an Agniṣṭoma, so-called because ten priests take part in drinking the Soma-liquor contained in each of the ten cups. After another year's interval[28], during which monthly 'offerings to the beams (i.e. the months)' are made, takes place 4, the Keśavapanīya, or hair-cutting ceremony, an Atirātra-sacrifice; followed, after a month or fortnight, by d, and 6, the Vyuṣṭi-dvirātra, or two nights’ ceremony of the dawning, consisting of an Agniṣṭoma and an Atirātra and finally 7, the Kṣatra-dhṛti, or 'the wielding of the (royal) power,' an Agniṣṭoma performed a month later. The round of ceremonies concludes with the Sautrāmaṇī, an iṣṭi the object of which is to make amends for any excess committed in the consumption of Soma-liquor.

The fifth book completes the dogmatic discussion of the ordinary circle of sacrifices, some less common, or altogether obsolete, ceremonies, such as the Aśvamedha (horse-sacrifice), Puruṣamedha (human sacrifice), Sarvamedha (sacrifice for universal rule), being dealt with, by way of supplement, in the thirteenth book.

With the sixth Kāṇḍa, we enter on the detailed explanation of the Agnicayana, or building of the fire-altar, a very solemn ceremony which would seem originally to have stood apart from, if not in actual opposition to, the ordinary sacrificial system, but which, in the end. apparently by some ecclesiastical compromise, was added on to the Soma ritual as an important, though not indispensable, element of it. The avowed object of this ceremony is the super-exaltation of Agni, the Fire, who, in the elaborate cosmogenic legend with which this section begins, is identified with Prajāpati, the lord of Generation, and the source of life in the world. As the present volume contains, however, only a portion of the Agnicayana ritual, any further remarks on this subject may be reserved for a future occasion.

Since the time when this volume went to press, the literature of the Soma myth has been enriched by the appearance of an important book, the first volume of Professor A. Hillebrandt's Vedische Mythologie, dealing with Soma and cognate gods. As it is impossible for me here to enter into a detailed discussion of the numerous points raised in the work, I must content myself for the present with the remark that I believe Professor Hillebrandt to have fully established the main point of his position, viz. the identity of Soma with the Moon in early Vedic mythology.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

See Katy. Sr. XIV, 1, 7; Lāṭy. Sr. VIII, 11, 7-11.

[2]:

In this enumeration the Vājapeya is often placed between the Atirātra and Aptoryāma; Lāṭy. V, 4, 24.

[3]:

Thus on Sat. Br. V, 1, 3, 1 Āgneyam agniṣṭoma ālabhate, Sāyaṇa remarks, 'agniḥ stūyate'sminn ity agniṣṭomo nāma sāma, tasmin viṣayabhūta āgneyam ālabhate, etena pasunā'smin vāgapeye'gniṣṭomasaṃsthaṃ kratum evānuṣṭhitavan bhavati.' In IV, 2, 4, 9 seq., also, the term 'agniṣṭoma' would seem to apply to the final chant rather than to the whole sacrifice.

[4]:

Each Sāman-tune is usually chanted thrice, either each time on a special verse of its own, or so that, by certain repetitions of words, two verses are made to suffice for the thrice-repeated tune.

[5]:

So also does the Agniṣṭut ekāha, cf. Tāṇḍya Br. XVII, 7.

[6]:

Sāyaṇa, to Sat. Br. IV, 3, 3, 2, explains it by 'stotra;' but see IV, 2, 3, 6-9 where it undoubtedly refers to the recited verses (ṛc), not to the sāman.

[7]:

Viz. from root 'vac' to speak. I cannot see the necessity for taking p. xv 'bṛhad vacas' in Rig-veda VII, 96, 1 in the technical sense of Bṛhat-tune, as is done by Prof. Hillebrandt, in his interesting essay, 'Die Sonnwendfeste in Alt-Indien,' p. 29, merely because it is used there in connection with Indra; whilst he himself is doubtful as to whether it should be taken in the same sense in III, 10, 5 where it occurs in connection with Agni. Though the Bṛhat-sāman is no doubt frequently referred to Indra, and the Rathantara to Agni, the couplets ordinarily chanted to them (Rig-veda VI, 46, 1-2 and VII, 32, 22, 23) are both of them addressed to Indra. Both tunes are, however, applied to verses addressed to all manner of deities.

[8]:

See Catalogue of Sanskrit MSS. of the India Office, No. 434. In Kaush. Br. XI, 8, 'sadasy ukthāni śasyante,' also, the word has undoubtedly the sense of śastra, or (recited) hymn. In part i, p. 346, note 3 of this translation read 'great recitation or śastra,' instead of 'great chant.'

[9]:

See, for instance, Tāṇḍya Br. XX, 1, 1.

[10]:

Perhaps the most characteristic point of difference between these two forms in which the fundamental stotras are chanted is the first (or Hotṛ's) Pṛṣṭha-stotra at the midday service. Whilst the Agniṣṭoma here requires the Rathantara-tune chanted on the text, Sāma-vela S. II, 30, 31; the Ukthya, on the other hand, requires the text, S. V. II, 159, 160, chanted to the Bṛhat-tune. Professor Hillebrandt, l.c., p. 22, has, indeed, tried to show that these two tunes play an important part in early India in connection with the celebration of the solstices. A similar alternation of sāmans to that of the Hotṛ's Pṛṣṭha-stotra obtains at the third, or Brāhmaṇācchaṃsin's Pṛṣṭha-stotra; the Naudhasa-sāman (II, 35, 36) being used at the Agniṣṭoma, and the Śyaita-sāman at the Ukthya-sacrifice. As regards the second (or Maitrāvaruṇa's) and fourth (or Acchāvāka's) Pṛṣṭha-stotras, on the other hand, the same sāman--viz. the Vāmadevya (II, 32-341 and Kāleya (II, 37, 3S respectively--is used both at the Agniṣṭoma and Ukthya.

[11]:

This is also the explanation of the term given by Sāyaṇa in his commentary on Tāṇḍya Br. XII, 13, 1.

[12]:

See this translation, part ii, p. 402, note 1.

[13]:

See part ii, p. 402, note 2, where it is stated that the tenth and last day of the Daśarātra is an Atyagniṣṭoma day, called Avivākya, i.e. one on which there should be no dispute or quarrel.

[14]:

See part ii, p. 226 seq. On the present occasion the Prātur-anuvāka is, however, to consist of as many verses as, counting their syllables, would make up a thousand bṛhatī-verses (of thirty-six syllables each). The three sections of the ordinary morning-litany from the body of the Āśvina-śastra which concludes, after sunrise, with verses addressed to Sūrya, the sun.

[15]:

Cf. Lāṭy. Sr. VIII, 1, 16; IX, 5, 23 with commentary.

[16]:

Notably Tāṇḍya Br. XX, 1, 1 seq.

[17]:

The Aitareya Brāhmaṇa (VI, 18) in discussing the so-called sampāta hymns inserted in continued performances, with the view of establishing a symbolic connection between the several days, curiously explains the term 'ahīna,' not from 'ahas' day, but as meaning 'not defective, where nothing is left out' (a-hīna).

[18]:

From Āśvalāyana's rule (IX, 11, 4), 'If they chant in forming the garbha (i.e. in the 'pṛṣṭha' form), let him (the Hotṛ or Hotraka) recite in the same way the stotriyas and anurūpas,' it seems, however, clear that the Aptoryāma may also be performed without the Pṛṣṭhas.

[19]:

The original text of the Sākvara-sāman is stated (by Sāyaṇa on Aitar. Br. IV, 13; Mahīdhara on Vāj. S. X, 14, &c.) to be Sāma-veda II, 1152-3, 'pro shv asmai puroratham,' but the Sāma-veda Gānas do not seem to give the tune p. xxi with that text, but with the Mahānāmnī verses (ed. Bibl. Ind. II, p. 371). The Tāṇḍya Br. XIII, 4 (and comm.), gives minute directions as to the particular pādas of the first three Mahānāmnī triplets which are singled out as of a śākvara (potent) nature, and are supposed to form the three stotriyā verses of the sākvara-sāman, consisting of seven, six, and five pādas respectively. The aśākvara pādas are, however, likewise chanted in their respective places, as is also the additional tenth verse, the five pādas of which are treated as mere supplementary (or 'filling in') matter.

[20]:

That is, the Vāravantīya-tune adapted to the 'Revatī' verses. The Vāravantīya-tune is named after its original text, Rig-veda I, 27, 1, 'aśvaṃ na tvā vāravantam' (Sāma-veda, ed. Bibl. Ind. I, p. 121). When used as one of the Pṛṣṭha-sāmans it is not, however, this, its original text, that is chanted to it, but the verses Rig-veda I, 30, 13-15, 'revatīr naḥ sadhamāda' (Sāma-veda II, 434-6, ed. vol. iv, p. 56), whence the tune, as adapted to this, triplet, is usually called Raivata. The Raivata-sāman, thus, is a signal instance of the use of the term 'sāman' in the sense of a chanted verse or triplet.

[21]:

The statement, in part ii, p. 403 note (and repeated in the present part, p. 6, note 2), that, while the Pṛṣṭha-stotras of the Abhiplava-ṣaḍaha are performed in the ordinary (Agniṣṭoma) way, the Pṛṣṭhya-ṣaḍaha requires their performance in the proper Pṛṣṭha form, is not correct. In both kinds of ṣaḍaha, the Pṛṣṭha-stotras are performed in the ordinary way (viz. in the Agniṣṭoma or Ukthya way, see p. 4 note); but whilst, in the Abhiplava, the Rathantara and Bṛhat sāmans are used for the Hotṛ's Pṛṣṭha-stotra on alternate days, the Pṛṣṭhya-ṣaḍaha requires a different Pṛṣṭha-sāman on each of the six days. The two kinds of ṣaḍahas also differ entirely in regard to the sequence of stomas prescribed for the performance of the stotras.

[22]:

Either the Rathantara or the Bṛhat also forms the 'pṛṣṭha,' or enclosing sāman, of the fist Pṛṣṭha-stotra.

[23]:

Whenever the stotra is not performed in the 'pṛṣṭha' form, but consists of a single sāman or triplet, the repetitions required to make up the number of verses implied in the respective stoma, are distributed over the three verses of the sāman in such a way that the whole sāman is chanted thrice, each time with various repetitions of the single verses. The usual form in which the p. xxiii ekaviṃśa is performed may be represented by the formula aaa-bbb-c; a-bbb-ccc; aaa-b-ccc, making together twenty-one verses.

[24]:

Āśval. Sr. IX, 3, 4-5.

[25]:

It is given somewhat imperfectly in the ed. Bibl. Ind. V, p. 391.

[26]:

Vedische Mythologie, p. 247.

[27]:

Cf. Śāṅkh. Sr. XV, 13, 4, 'for it is Varuṇa whom they consecrate.'

[28]:

The Brāhmaṇa (V. 5, 2, 2), however, would rather seem to dispense with this interval by combining the twelve oblations so as to form two sets of six each.