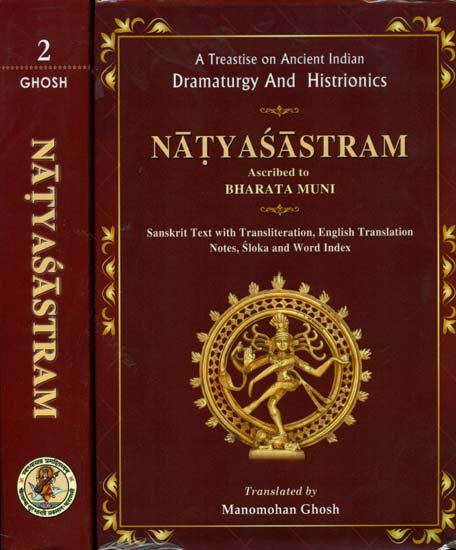

Natyashastra (English)

by Bharata-muni | 1951 | 240,273 words | ISBN-13: 9789385005831

The English translation of the Natyashastra, a Sanskrit work on drama, performing arts, theater, dance, music and various other topics. The word natyashastra also refers to a global category of literature encompassing this ancient Indian tradition of dramatic performance. The authorship of this work dates back to as far as at least the 1st millenn...

Part 4 - More About the Ancient Indian Theory and Practice of Drama

1. The Three Types of Character

Characters of all kinds male, female and hermaphrodite in the ancient Indian plays, were classified into three types: superior, inferior and middling[1], for the purpose of distinguishing them by assigning to them special movements to be followed by appropriate music and drumming. Division of Heroes (nāyaka) and Heroines (nāyikā) into four classes, had also included the same purpose.

2. The Prominent Position of the Nāṭaka

From the very detailed description given in the NŚ of the various types of character such as the king and his entourage, inside and outside the royal palace[2], it appears that the Nāṭaka which usually include such characters, was the most prominent among the ten kinds of play. The special purpose of the description seems to have been to help the playwrights who cannot always be expected to possess a first-hand knowledge of habits and customs of such characters.

3. The Typical Theatrical Troupe

From a detailed description of the various members of theatrical troupes[3], it appears that such troupes moved from place to place just like the Bengali Jātrâwālās, to give performance before people of different regions. It is only on the assumption of this kind that we may easily explain inclusion into the troupe, of such members as makers of headgears (mukuṭakāraka) and of ornaments, the dyer (rajaka), the painter and craftsmen of various kinds. If like the members of modern theatres of India they were restricted in their activity to any particular place, there might not have been any necessity of counting them as members of theatrical troupes. As communication and transport at that ancient time were not easy, the theatrical parties did not

probably like to add to their luggage in the shape costumes and other paraphernalia of a dramatic performance. Skilled persons who accompanied them prepared these anew in every region, and these were used for a number of performances held in places not very distant from one another. The Arthaśāstra of Kauṭilya seems to envisage this kind of itinerant theatrical troupes.

4. The Playwright as a Member of the Theatrical Troupe

The playwright (nāṭyakāraka)[4] appearing as one of the members probably shows also that theatrical troupes moved from place to place and did not depend exclusively on a fixed repertoire, but often constructed special plays based on local history or popular legends, to suit the taste and interest of the people before whom they were called upon to give a performance.

The position of the playwrights was probably analogous to some extent to their modern counterparts attached to some urban theatres of modern India, which employ them for salary with the purpose of making their dramatic compositions the exclusive property.

5. Distribution of Roles

The NŚ lays down some general principles for the distribution of roles in a play.[5] For example, it says:

“After considering together their gait, speech and movement of the limbs, as well as their strength and nature, the experts are to employ actors to represent different roles [in a play]”[6]

“Hence the selection of actors should be preceded by an enquiry into their merits. The Director will have no difficulty over the choice [if such a procedure is followed]. After ascertaining their natural aptitudes, he is to distribute roles to different actors”.

To clarify further these principles, the NŚ adds:

“Persons who have all the limbs intact, well-formed and thick-set, who are full-grown, not fat or lean, or tall or large, who

have vivacity, pleasant voice and good appearance, should be employed to represent the role of gods.[7]

“Persons who are fat, and have a large body, a voice like the peal of thunder, furious looking eyes, and naturally knit eye-brows should be employed to represent the role of Rākṣasas, Dānavas and Daityas; for the performance of the male actors [should be] in conformity with their limbs and movements”.[8]

“Actors of the best kind who have beautiful eyes, eye-brows, forehead, nose, lips, cheeks, face, neck and every other limb beautiful, and who are tall, possessed of pleasant appearance and dignified gait, and are well-behaved, wise, steady by nature, should be employed to represent the role of kings and princes.[9]

In a similar manner the NŚ gives directions about assigning roles of army-leaders, councillors (ministers and secretaries) Kañcukins, the Śrotriyas[10] as well as minor characters.[11] The directions about the representation of fatigued and healthy characters show how careful the ancients were about the assignment of roles. For the NŚ says.

“A person who is naturally thin should be employed in a play to represent tired characters.”[12]

“A fat man should be employed to represent persons without any disease”.[13]

From the very elaborate rules quoted above, it appears that the author of the NŚ was very careful in the assignment of roles. His rules were often found difficult to be carried into practice. But in spite of this, he was not a doctrinaire in this regard, and permitted the Directors of theatres to train up properly persons available, even when they did not come up to the standard. On this point he says:

“If however, such persons are not available, the Director should exercise discretion to employ [some one] after a consideration of the latter’s nature and movement as well as all the States [to be represented].”

“Such persons’ natural movements whether good, bad or. middling, should be regulated by a contact with the Director and then they will properly represent all the States”[14].

6. The Principles of Personation

The NŚ also very clearly laid down the principles of personation. It says “One should not enter the stage in his own natural appearance. His own body should be covered with paints and decorations”[15].

“In the production of a play, a person in his natural form of the body should be employed [to assume a role) according to his age and costume”[16].

“Just as a man who renounces his own nature together with the body, and assumes nature of someone else by entering into his body, so the wise actor thinking within himself that “I am he”, should represent the States of another person by speech, gait, gestures and other movements”[17].

The stage-representation of characters according the NŚ, are of three kinds: natural (anurūpa) unnatural (virūpa) and imitative (rupānusāriṇī)[18].

These three kinds of representation are described as follows:—

“When women impersonate female characters and men male characters and their ages are similar to that of characters represented, the impersonation is called natural[19]”

“When a boy takes up the role of an old man or an old man that of a boy and betrays his own nature, the representation is called unnatural[20].

When a man assumes a woman’s role, the impersonation is called imitative by the best actor. A woman also may assume if she likes, a man’s role in actual practice. • But an

old man and a young man should not try [to imitate] each other’s manners[21].

7. Special Importance of Women in Dramatic Production

Unlike what was the practice in ancient Greece or in medieval Europe, ancient Indians had no scruple to employ actresses possibly from the very ancient times. Hence the NŚ points out their special fitness on certain points.

The relevant passages in the NŚ are as follows:—

“A delicate person’s role is always to be taken up by women. Hence in case of women as well as gods and men of delicate nature [women are to assume the roles]. [It is for this reason that] drama came to be established in heaven through Rambhā, Urvaśī and the like [nymphs]. And similar has been the case in king’s harems in this world”[22]. “Want of fatigue in dance and music, is always considered a quality of women, and a dramatic production partly attains its sweetness and partly its strength due to this”[23].

“This delicate type of production is pleasing to kings. Hence plays of this class including the Erotic Sentiment, should be produced by women”[24]. An instance of the production of a play exclusively by women occurs in the Priyadarśikā (III) of Harṣa. Also in Cambodia the country which owes its drama to India, plays are produced exclusively by women[25]. In the palaces of some Sultans of Java too, women are exclusive performers of dance-dramas[26]. It can scarcely be doubted that this practice had its origin in India in hoary antiquity and the relevant passage of the NŚ, quoted above, seems to support our assumption.

8. Impersonation of a King

Though the NŚ has given description of a person suited to represent a royal character[27], it closes the topic of impersona

tion by giving rather elaborate directions about the impersonation of a king. On this point it says:

“How are the qualities of a king to be represented by an actor who has a few wearing apparels? In this connection it has been said that when dramatic conventions have come into vogue I have made plays furnished with all these (i.e. conventions)”.

“In them (i.e. plays) the actor (naṭa) covered with paint, and decorated with ornaments, reveal the signs of kingship when he assumes a grave and dignified attitude and then he alone becomes, as it were, a refuge of the seven great divisions (saptadvīpa) of the world”[28].

“He should move his limbs only after he has been covered with paints. And trimmed according to the discretion of the Director and having the Sauṣṭhava of limbs, the actor becomes like a king, and [thus trimmed] the king also will be [very much] like an actor. Just as the actor is, so is the king, and just as a king is, so is the actor”[29].

9. An Ideal Director

Principles and practices of the ancient Hindu drama as described before, placed a very great responsibility on the Director of a theatre. Hence the NŚ describes the characteristics of an ideal Director as follows:—

He should have “a desirable refinement of speech, knowledge of the rules of Tāla, the theory of notes and instruments [in general]”. And he who is “an expert in playing the four kinds of instruments, has various practical experience, is conversant with the practices of different religious sects, and with polity, science of wealth and the manners of courtezans, ars amatoria and knows various conventional gaits and movements, thoroughly understands all the sentiments and the states, and is an expert in producing plays, acquainted with all arts and crafts, with words and rules of prosody, and proficient in all the Śāstras, the science of stars and planets and the working of the human body, knows the extent of the earthly continents, divisions, and mountains, and people inhabiting them, and customs they have, and the names of descendants of royal

lines, and who listens about acts prescribed in Śāstras, can understand the same, and puts them into practice after understanding them and gives instruction in the same, should be made a Director.[30]

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

See XXXIV. 2ff.

[2]:

See XXXIV. 29ff.

[3]:

See XXXV. 89-99.

[4]:

See XXXV. 99.

[5]:

See XXXV.

[6]:

See XXXV. XXXV. 5-6.

[7]:

XXXV. 5-6.

[8]:

XXXV. 7-8.

[9]:

XXXV. 9-11.

[10]:

XXXV. 12-14.

[11]:

XXXV. 15-17.

[12]:

XXXV. 18.

[13]:

Ibid.

[14]:

XXXV. 19-20.

[15]:

XXXV. 24.

[16]:

XXXV. 25.

[17]:

XXXV. 26-27.

[18]:

XXXV 28.

[19]:

XXXV. 29.

[20]:

XXXV. 30.

[21]:

XXXV. 31-32.

[22]:

XXXV. 38-39.

[23]:

XXXV. 44.

[24]:

XXXV. 49.

[25]:

See the author’s Contributions to the History of Hindu Drama, Calcutta, 1957, p. 41.

[26]:

See notes on XXXIV. 48-51.

[27]:

XXXV. 9-11.

[28]:

XXXV. 57-59.

[29]:

XXXV. 60-59.

[30]:

XXXV. 65-71.