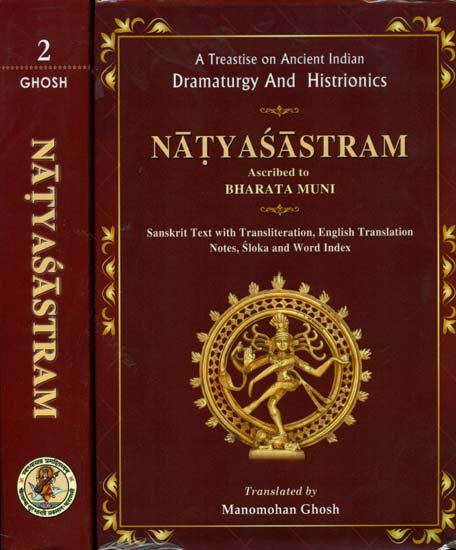

Natyashastra (English)

by Bharata-muni | 1951 | 240,273 words | ISBN-13: 9789385005831

The English translation of the Natyashastra, a Sanskrit work on drama, performing arts, theater, dance, music and various other topics. The word natyashastra also refers to a global category of literature encompassing this ancient Indian tradition of dramatic performance. The authorship of this work dates back to as far as at least the 1st millenn...

Chapter XVIII - Rules on the use of Languages (bhāṣā)

Prakritic Recitation

1.[1] Thus I have spoken in brief[2] of the Sanskritic Recitation. Now I shall speak of the characteristics of the Prakritic Recitation.

2. The former (lit. this) [when] changed and devoid of the quality of polish, is called the Prakritic Recitation, and it has as its chief feature changes due to different conditions.[3]

Three kinds of Prakrit Recitation

3. In connexion with the dramatic representation, it (the Prakrit recitation) is of three[4] kinds, viz, that with the same words [as in Sanskrit] (samāna-śabda), that with corrupt (vibhraṣṭa) words and that with words of indigenous origin (deśī).

4. A sentence containing words like kamala, amala, reṇu, taraṅga, lola, salila and the like are used in the Prakrit composition [in the same manner] as in Sanskrit.[5]

5.[6] Sounds which change their combined form or vowels, or sustain loss and that often in the middle of a word are corrupt (vibhraṣṭa).

Vowels and simple consonants

6. Sounds following e and o (i.e., ai and au) and the Anusvāra [in the alphabet] do not occur in Prakrit. And such is the case with sounds between va and sa (i.e., śa and ṣa) and the final sounds in the ka, ca and ta groups (i.e., ṅa, ña, na).[7]

7.[8] Ka, ga, ta, da, ya, and va are dropped [in Prakrit] and the meaning is carried by the [remaining] vowels, and kha, gha, tha, dha and bha become ha without giving up the meaning of the word.

8. In Prakrit ra does neither precede nor follow [a Consonantal sound] except in cases of bhadra, vodra, hrada, candra and the like.[9]

9. Kha, gha, tha, dha and bha always become ha in words such as mukha, megha, kathā and vadhu prabhūta.[10] And as for ka, ga, ta, da, ya[11] and va, the vowel[12] following them always represents them.

10. Ṣa it should be known, always become cha in words such as ṣaṭpada.[13] The final syllable of kila should be ra and the word khalu should become khu.

11. Ṭa becomes ḍa in words such as bhaṭa, kuṭi, and taṭa, and śa and ṣa always become sa, e.g. viṣa (visa) and saṃkā (śaṅkā).

12. In words such as itara and the like, ta standing not in the beginning of a word becomes an indistinctly pronounced da.[14] Ḍa in words such as vaḍavā and taḍāga becomes la.

13. Dha in words such as vadha and mādhū (madhu?) become dha, and na becomes ṇa everywhere in pronunciation.

14. Pa [in it] changing into va, āpāna becomes āvāṇa. And except in case of words like yathā and tathā, tha becomes dha.

15. One is to know paruṣa as pharusa, for fa becomes pha [in it], and mṛga will be changed to mao while mṛta will also be mao.[15]

16. Au employed in words like auṣadha etc. will change to o, and ca in words such as pracaya, acira and acala etc. will change into ya.[16]

17. Thus [change] the sounds in Prakrit when they are not mutually connected (i.e. they are simple). Now I shall describe the change of conjunct sounds.

Conjunct consonants

18. Śca, psa, tsa and thya change into (c)cba, bhya, hya and dhya into (j)jha, ṣṭa into ṭṭha, sta into ttha, sma into mha, kṣṇa and ṣṇa into ṇha, and kṣa into (k)kha.

19. Āścarya will be acchariya and niścaya nicchaya, utsāha ucchāha and pathya, paccha.[17]

20. Tubhyam becomes tujjhaṃ, mahyam majjhaṃ, vindhya viṃjha, daṣṭa daṭṭha and hasta hattha.

21. Grīṣma becomes gimha, ślakṣna saṇha, uṣṇa uṇha; jakṣa jakkha, and paryaṅkā pallaṃka.

22. There is metathesis in the group hma occurring in words such as brahman etc., and in bṛhaspati [the group spa ] becomes pha, yajña becomes jaṇṇa, bhīṣma bhimha.

23. Ka and similar other letters (sound) while on the top of another letter (sound) will have to be disjointed in their pronunciation.[18]

24.[19] Thus are to be learnt the pronunciations of Prakrit and Sanskrit. I shall discuss hereafter the classification of regional languages (deśa-bhāsa).

25. The [languages] to be used in drama are of four types in which Recitation should be either of the refined (saṃskṛta) or of the vulgar (prākṛta) kind.

Four types of language

26. The Super-human Language (atibhāṣā), the Noble Language (ārya-bhāṣā)[20] the Common Language (jāti-bhāṣā) and the Language of Other Animals (yonyantarī bhāṣā)[21] are the [four] languages occurring in plays.

The Superhuman and the Noble Languages

27. The Super-human Language is for the gods, and the Noble language for the kings.[22] These have the quality of refinement (saṃṣkāra) and are current oyer the seven great divisions[23] (dvīpa) of the world.

The Common Language

28. The Common Language prescribed for use [on the stage] has various forms. It contains [many] words of Barbarian (mleccha) origin and is spoken in Bhārata-varṣa [only].[24]

The Animal Language

29. The Language of Other Animals[25] have their origin in animals domestic or wild, and in birds of various species, and it follows the Conventional Practice.

Two kinds of Recitation

30. The Recitation in the Common language which relates to the four castes, is of two kinds, viz, vulgar (prākṛta) and refined (saṃskṛta).

Occasion for Sanskrit Recitation

31. In case of the self-controlled (dhīra) Heroes of the vehement (uddhata), the light-hearted (lalita), the exalted (udātta), and the calm (praśānta) types, the Recitation should be in Sanskrit.

Occasion for Prakrit Recitation

32. Heroes of all these classes are to use Prakrit when the occasion demands that.[26]

33. In case of even a superior person intoxicated with the kingship (or wealth) or overwhelmed with poverty no Sanskrit should be used.[27]

34. To persons in disguise,[28] Jain monks,[29] ascetics,[30] religious mendicants[31] and jugglers should be assigned the Prakrit Recitation.

35.[32] Similarly Prakrit should be assigned to children, persons possessed of spirits of lower order, women in feminine character[33] persons of low birth, lunatics and phallus-worshippers.[34]

Exception to the rule for Prakrit Recitation

36. But to itinerent recluses,[35] sages,[36] Buddhists,[37] pure Śrotriyas[38] and others who have received instruction [in the Vedas] and wear costumes suitable to their position (liṅgastha)[39] should be assigned Sanskritic Recitation.

37. Sanskrit Recitation is to be assigned to queens, courtezans,[40] female artistes to suit special times and situations in which they may speak.

38-39. As matters relating to the peace and war may occur in course of a talk and the movements of planets and stars and cries of birds concerning the well-being or distress of the king are to be known by the queen, she is to be assigned Sanskritic Recitation in connexion with these (lit. in that time).[41]

40. For the pleasure of all kinds of people, and in connexion with the practice of arts, the courtezans are to be assigned Sanskritic Recitation which can be easily managed.

41. For learning the practice of arts and for amusing the king the female artiste has been prescribed to use Sanskrit recitation in dramatic works.[42]

42. The pure speech of Apsarasas[43] is that which has been sanctioned by the tradition (i.e. Sanskrit), because of their association with the gods; the popular usage conforms to this [rule].

43. One may however at one’s pleasure assign Prakritic Recitation to Apsarasas [while they move] on the earth. [But to the Apsarasas in the role of] the wife of a mortal also [the same] should be assigned when an occasion (lit. reasons and need) will occur.[44]

44. In the production of a play their [native] language should not be assigned to tribes such as, Barbaras, Kitātas, Andhras and Dramiḍas.[45]

45. To pure tribes of these names, should be assigned dialects current in Śūrasena.

46. The producer of plays may however at their option use local dialects for plays may be written in different regions [for local production].

Seven major dialects

47. The Seven [major] dialects (bhāṣā) are as follows: Māgadhī, Āvantī [Avantijā], Prācyā, Śaurasenī (Śūrasenī), Ardhamāgadhī, Bāhlīkā, Dākṣiṇātyā.[46]

48. In the dramatic composition there are, besides, many less important dialects (vibhāṣā)[47] such as the speeches of the Śakāra, Ābhīras, Caṇḍālas, Śabaras, Dramiḍas,[48] Oḍras, and the lowly speech of the foresters.

Uses of major dialects

49. [Of these] Māgadhī is assigned to guards (lit. inmates) of the royal harem,[49] and Ardhamāgadhī to menials, princes and leaders of bankers’ guilds.[50]

50. Prācyā is the language of the Jester[51] and the like; and Āvantī is of gallant crooks (dhūrta).[52] The Heroines, and their female friends are also to speak Śaurasenī without in any exception.

51. To soldiers, gamesters, police chief of the city and the like should be assigned Dākṣiṇātyā,[53] and Bāhlikī is the native speech of the Khasas who belong to the north.

Uses of minor dialects

52. Śākārī should be assigned to the Śakāra and the Śakas and other groups of the same nature,[54] and Cāṇḍālī to the Pulkasas and the like.[55]

53. To charcoal-makers, hunters and those who earn their livelihood by [collecting] wood and leaves should be assigned Śābari[56][57] as well as the speech of forest-dwellers.

54. For those who live in places where elephants, horses, goats, sheep, camels or cows are kept [in large numbers] Ābhīrī[58] or Śābarī[59] has been prescribed, and for forest-dwellers and the like, Drāviḍī[60] [is the language].

55. Oḍri is to be assigned to diggers of subterranean passages, prison-warders, grooms for horses;[61] and Heroes and others like them while in difficulty are also to use Māgadhī for self-protection.

Distinguishing features of various local dialects

56.[62] To the regions [of India] that lie between the Ganges and the sea, should be applied a dialect abounding in e[63].

57. To the regions that lie between the Vindhyas and the sea should be assigned a language abounding in na[64] (or ta).

58. Regions like Surāṣṭra and Avanti lying on the north of the Vetravatī one should assign a language abounding ca[65].

59. To people who live in the Himalayas, Sindhu and Sauvīra a language abounding in u should be assigned.[66]

60. To those who live on the bank of the Carmaṇvatī river and around the Arvuda mountain a language abounding in o[67] (or ta) should be assigned.

61. These are the rules regarding the assignment of dialects in plays. Whatever has been omitted [here] should be gathered by the wise from the popular usage.

Here ends Chapter XVIII of Bharata’s Nāṭyaśāstra, which treats of the Rules regarding the Use of Languages.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

For an English translation (with the text and notes) of XVIII, 1-24, see M. Ghosh, “Date of the Bharata-Nāṭyaśāstra,” JDL, Vol. XXV. (1933). For a French translation (together with the romanised text) of this chapter see L. Nitti-Dolci, Les Grammairiens Prakrits, 1938, pp. 64-76.

[2]:

samāsataḥ (C. dvijottamāḥ).

[3]:

Cf. Nitti-Dolci, p. 70.

[4]:

Later Prakrit Grammarians called the above three classes of words tatsama, tadbhava and deśī respectively.

[5]:

B. reads one additional hemistich (4a) before this. Cf. Nitti-Dolci, p. 20.

[6]:

Cf. Nitti-Dolci, p. 70.

[7]:

This together with three following couplets are written not in Sanskrit but in Prakrit. Hence they should be taken as an interpolation. The first of these occurs as a quotation (without the author’s name) in a late work on metrics edited by M.H.D. Velankar (Annals of the Bhandarkar Inst. XIV. 1932-33, pp. 1-38, citation of Nitti-Dolci, p. 71).

[8]:

Nitti-Dolci and B. reads padra for draha. See the chāyā in B, and Ag., and also PSM. for the Prakrit words. Cf. Nitti-Dolci, p. 71.

[9]:

See the chāyā in B., and Ag. and also PSM. for the Prakrit words. Cf. Nitti-Dolci, p. 71.

[10]:

Evidently the hard aspirates in case of other words did not change. Ag’s, example of such words are kheṭa, parigha, atha. This speaks of the high antiquity of the Prakrit of the NŚ, though not of these rules written in Pkt.

[11]:

The non-aspirate consonants mentioned here are to be understood as devoid of the inherent vowel ‘a’.

[12]:

The word saro (= svaraḥ) here means “vowel” and not “sound”. Cf. Nitti-Dolci p. 71.

[13]:

Ag. is silent about this ṣaṭpadādi gaṇa.

[14]:

This indistinctly pronounced da is perhaps a spirantised da. Ag. thinks that it is somewhat like a la.

[15]:

The word maa (mayo) from mṛta as well as mṛga had its spirantised da reduced to ya-śruti which however was not shown in writing during the early days of this phonetic change (See IHQ. VIII. 1933, suppl. p. 14-15).

[16]:

This ya-śruti for ca did not probably at once lead to its graphic elimination.

[17]:

B. reads one additional hemistich between 19a and 19b.

[18]:

This probably relates to svarabhakti (anaptyxis). Kilesa (kleśa), radana (ratna) and duvāra (dvāra) may be examples of this.

[19]:

Cf. Nitti-Dolci. p. 73-

[20]:

Some commentators think that ārya-bhāṣā means a language in which Vedic words preponderate (Ag.).

[21]:

C. reads jātyantarī for yonyantarī.

[22]:

The atibhāṣā and āryabhāṣā are possibly the dialects of the pure Indo-Aryan speech. It should be noted that “saṃskṛta” (Sanskrit) as the name of a language is absent here. Bhoja takes ati -, ārya- and jāti - bhāṣas respectively as śrauta (Vedic), ārṣa (Purāṇic) and laukika (literary) speeches. See Śr. Pr. ed, V. Raghavan pp, 191ff.

[23]:

This may be said to show that Sanskrit was used all over the civilized world at the time of the NŚ.

[24]:

The common speech or the speech of the commoners is distinguished here from that of the priests and the nobility by describing it as containing words of Barbarian (mleccha) origin. These words seem to have been none other than vocables of the Dravidian and the Austric languages. They entered into Indo-Aryan quite early in its history. See S. K, Chatterji, Origin and Development of the Bengali Language, Calcutta, 1926. pp. 42, 178.

[25]:

Neither the NŚ. nor any extant drama gives us any specimen of the conventional language of lower animals, which is to be used in the stage.

[26]:

As Arjuna disguised as Bṛhannalā.

[27]:

No extant drama seems to furnish any illustration of this rule. B. reads one additional hemistich before this.

[28]:

vyājaliṅgapraviṣṭānām = persons in disguise of different kinds of professional and religious mendicants etc. See Kauṭilya’s Arthaśāstra. An example of this is Indra in the guise of a Brahmin speaking Prakrit in Karṇa, ascribed to Bhāsa. Nitti-Dolci takes this expression as an adjective of śramaṇāṇāṃ etc. But it need not be construed like this. This part of the rule seems to relate to Skt.-speaking characters assuming disguise. Virādhagupta (Mudrā. II.) assuming the guise of a snake-charmer, is an example of such characters. And so are Yaugandharāyaṇa and Rumaṇvān in the Pratijñā, (III) ascribed to Bhāsa.

[29]:

Śramaṇa (Prakrit samaṇa). The word is to be taken to mean here a Jain monk. See Jadi vattbam avaṇemi samaṇao homi, Avi. (V.) ascribed to Bhāsa; śramana was sometimes used also in connexion with the Buddhists. See below 36.

[30]:

tapasvin.—It appears that the author of the NŚ. meant by this term ascetics in general. Though we find Brahmin ascetics in ancient literature, the institution of asceticism was most probably of non-Aryan origin. This seems to be the justification of assigning Prakritic Recitation to all the ascetics irrespective of their sectarian affiliation.

[31]:

bhikṣu.—religious mendicant in general. It should not be restricted to Buddhists alone. The alternative name of the Brahma-sūtra is the Bhikṣu-sūtra.

[32]:

B.’s reading in translation is as follows: Similarly Prakrit should be assigned to Śaiva teachers, lunatics, children, persons possessed of spirits of lower order, women, persons of low birth and hermaphrodites (B.XVII.37).

[33]:

In a queen’s role a woman may sometimes speak Sanskrit See 38-39 below. The parivrājikā in the Mālavi. speaks Sanskrit.

[34]:

saliṅga.—This possibly means the member of a sect which like the Liṅgā-yets wears a phallus suspended from their neck.

[35]:

(C.34b-35a; B.XVII.38).1 parivrāj—a person of the fourth āśrama. A recluse belonging to the Vedic community.

[36]:

muni.—This word, probably of non-Indo-Aryan origin meant in all likelihood “wise man.” See NŚ. I.23 note 1. In the ancient world, wisdom was usually associated with religious and spiritual elevation. This might have been the reason why the word was applied to persons like Vaśiṣṭha and Nārada etc.

[37]:

śākya.—a follower of the Buddha. There is nothing very astonishing in Sanskrit being assigned to Buddhist monks. Buddhist teachers like Aśvaghoṣa, Nāgārjuna, Āryadeva, Vasubandhu were the all very great Sanskritists, and the Mahāyāna literature was written in the Sanskrit of corrupt as well as of pure variety. This might have been the general linguistic condition before the schism arose among the Buddhists. In Aśvaghoṣa’s Śāriputra-parakaraṇa Buddha and his disciples speak Sanskrit (Keith, Sanskrit Drama p.82). Aśvaghoṣa assigns Sanskrit to a śramaṇa as well (loc. cit). This śramaṇa was possibly a Buddhist; see 34 f.n.

[38]:

caukṣeṣu (caikṣeṣu, C.) śrotriyeṣu—for the pure śrotriya or a learned Brahmin. The adjective “pure” (caukṣa) used with śrotriya is possibly to separate him from an apostate who might have entered into Jain or any other heterodox fold and was at liberty to use Prakrit. Ag. takes caukṣesu (his cokṣeṣu) as a noun.

[39]:

śiṣṭāḥ liṅgasthāḥ—religious mendicants who have received instruction (in Vedas).

[40]:

An example of this is Vasantasenā speaking Sanskrit (Mṛcch. IV.).

[41]:

This not very clear rule cannot be illustrated by any extant drama.

[42]:

This is possibly no example of this in any extant drama.

[43]:

No play with an Apsaras speaking Sanskrit is available. All the Apsarasas in Vikram, speak Prakrit.

[44]:

Urvaśī is an example of an Apsaras who became the wife of a mortal. (Vikram).

[45]:

See XXIII. 99 notes.

[46]:

Māgadhī, Śaurasenī and Ardhamāgādhī are well-known. But any old and authentic description of Āvantī, Prācyā, Bāhlīkā and Dākṣiṇātyā Prakrit seems to be non-existent. According to Pṛthvīdhara, a very late authority Mṛcch. contains the specimens of Āvantī and Prācyā only. It is to be noted that the present list does not include Mahārāṣṭrī. See M. Ghosh. “Mahārāṣṭrī, a late phase of Śauraseni,” JDL. XXIII

[47]:

By the word vibhāṣā Pṛthvīdhara understands vididhā bhāṣā hīna - pātra-prayojyatvād hīnāḥ. See Pischel, Grammatik, §§ 3-5. No old and authentic specimen of the vibhāṣās has reached us. According to Pṛthvīdhara the Mṛcch. contains Śākārī and Cāṇḍālī besides Ḍhakkī which last the NŚ. does not know.

[48]:

It is curious that after forbidding the use of languages like Dramiḍa (Dramila) in 44 above, the author is including it among the dialects that can be allowed in dramatic works. One possible explanation of this anomaly may be that here we meet with a late interpolation, and passages from 48-61 belong to a later stratum of the text.

[49]:

For a list of such persons see DR. II.74.

[50]:

According to Pischel this passage assigns AMg. to servants, Rajputs (rājaputra) and leaders of bankers’ guild (śreṣṭhī). See Grammatik § 17. But no extant drama seems to illustrate this rule. For Candanadāsa who is a śreṣṭhī, does not speak AMg. (Mudrā, I) while Indra in the disguise of a Brahmin speaks this dialect of Prakrit (Karṇa, ascribed to Bhāṣa).

[51]:

According to Pṛthvīdhara Vidūṣaka in the Mṛcch. speaks Prācyā the sole characteristic of which is abundance of pleonastic ka. See Pischel, Grammatik, § 22.

[52]:

According to Pṛthvīdhara the two policemen Vīraka and Candanaka in the Mṛcch. (Vā.) speak Āvantī. But according to the latter’s own admission he was a Southerner and a man of Karṇāta. No old and authentic description of this dialect is available. See Pischel, Grammatik § 26.

[53]:

Candanaka’s language in Mṛcch. in spite of Pṛthvīdhara’s testimony to the contrary may be taken as a specimen of Dākṣinātyā. See 50 note 2 above. No old and authentic description of this dialect is available. Cf. Pischel, Grammatik § 24.

[54]:

According to Pṛthvīdhara, Śakāra in Mṛcch. speaks Śākārī dialect. Cf. Pischel, Grammatik, § 24.

[55]:

Pṛthvīdhara thinks that Caṇḍālas in Mṛcch (V.) speak the Cāṇḍali dialect. Cf. Pischel, Grammatik, § 25.

[56]:

This dialect seems to have been the parent of the modern Sora language.

[57]:

See 54 note 3.

[58]:

Ābhīrī dialect is not available in any extant drama.

[59]:

See 53 note 1.

[60]:

Drāvidī dialect is not available in any extant drama. It is possible that it was not a pure Dravidian speech (See 44 above). Possibly a Middle Indo-Aryan dialect in which Dravidian phonetic and lexical influence predominated was meant by this. Its habitat was in all likelihood some region of North India. Cf. Nitti-Dolci, p. 120-122.

[61]:

For Oḍri Prakrit see 48 note 3. and Nitti-Dolci, pp. 120 f.n. 4 and 122.

[62]:

B. again reads 44 after 55.

[63]:

This “e” is perhaps termination of the nominative singular the a -bases in Mg. and AMg.

[64]:

This relates to a dialeet of Prakrit which does not change na always into ṇa. Though according to some grammarians Prakrit is always to change na into ṇa, it seems that such was not strictly the case with all its dialects. For example in the so-called Jain Prakrit (AMg. of Hemacandra) has initial n and in ter vocal nn.

[65]:

It seems that at the time of the author of the passage intervocal ca in this particular region was yet maintained or dental t sounds were mostly changed into c sound (as in ciṭṭha for tiṣṭha),

[66]:

This u perhaps relates to a close pronunciation of the o vowel.

[67]:

This o perhaps relates to an open pronunciation of the u vowel.