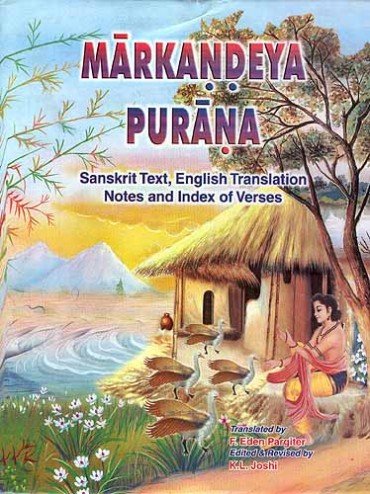

The Markandeya Purana

by Frederick Eden Pargiter | 1904 | 247,181 words | ISBN-10: 8171102237

This page relates “madalasa’s exhortation (continued)” which forms the 29th chapter of the English translation of the Markandeya-purana: an ancient Sanskrit text dealing with Indian history, philosophy and traditions. It consists of 137 parts narrated by sage (rishi) Markandeya: a well-known character in the ancient Puranas. Chapter 29 is included the section known as “conversation between Sumati (Jada) and his father”.

Canto XXIX - Madālasā’s Exhortation (continued)

Madālasā explains to Alarka the position of a gṛhastha—and personifies as a cow, the Vedas, pious acts, the words of the good and the words svāhā, svadhā, vaṣaṭ and hanta—She describes the bali offering, and utsarga oblation—the duties of a gṛhastha to guests—the śrāddha—and further duties to guests—She pronounces a blessing on the gṛhastha state—and quotes a song by Atri on it.

Alarka spoke:

“And what men must do who are engaged in the gṛhastha period; and what becomes confined in the absence of action, and what increases by action; and what is beneficial to men; and what a good man should avoid at home; and how things are done—declare that accurately to me who ask.”

Madālasā spoke:

“My child, a man on assuming the gṛhastha status, thereby nourishes all this earth and conquers the worlds he longs for. The pitṛs, the Munis, the gods, living things, and mankind, and worms, insects, and flying creatures, birds, cattle, and Asuras subsist upon the gṛhastha, and derive satisfaction from him; and gaze indeed at bis countenance, wondering, ‘Will be give us anything?’

“The support of everything is this cow, my child, which consists of the three Vedas, in which the universe is established, and which is believed to be the cause of the universe. Her back is the Ṛg-Veda; her loins the Yajur-Veda; her face and neck the Sāma-Veda; and her horns are pious acts; her hair the excellent words of the good; her ordure and urine are tranquillity and prosperity; she is supported on feet which are the four classes; she is the sustenance of the worlds; being imperishable she does not wane. The word svāhā,[1] and the word svadhā,[2] and the word vaṣaṭ, my son, and the other word hanta are her[3] four teats. The gods drink of the teat which is the word svāhā; and the pitṛs of that consisting of svadhā; and the Munis of that which is the word vaṣaṭ; the gods, living things and Asuras, and mankind drink constantly of the teat which is the word hanta. Thus this cow consisting of the three Vedas, my child, fattens them. And the man, who grievously sinning causes their destruction, sinks into the hell Tamas,[4] the hell Andhatāmisra[5] and the hell Tāmisra.[6] And the man, who gives this cow drink with his own children and with the immortals and other objects of worship at the proper time, attains Svarga.

“Therefore, my son, a man must nourish the gods, ṛṣis, and pitṛs and men and living things daily, even as his own body. Therefore having bathed and become clean he should, composed in mind, delight the gods, ṛṣis and pitṛs, and the prajāpati also with water at the proper time. And a man[7] having worshipped the gods with the fragrant flowers of the great-flowered jasmine, should next delight Agni; and the bali offering should also be made. Let him cast the bali offering to Brahmā and the Viśvadevas inside the house, and to Dhanvantari to the north-east; let him offer the bali eastward to Indra, southwards to Tama., and the hali westwards to Varuṇa, and northwards to Soma. And let him also give the hali to Dhātṛ and Vidhātṛ at the house-door, and let him give it to Aryaman outside and all around the houses. Let him offer the bali to night-walking goblins in the air, and let him scatter it to the pitṛs, standing with his face southward. Then the gṛhastha, being intent and having his mind well composed, should take the water and cast it, as a wise man, into those places for those several deities, that they may rinse out their mouths.

“Having thus performed in his house the family-bali, the pure gṛhastha should perform the utsarga oblation respectfully for the nourishment of living things. And let him scatter it on the ground both for the dogs, and low-caste men and the birds; for certainly this offering to the Viśvadevas is declared to be one for evening and morning.

“And then he, as a wise man, having rinsed out his mouth, should look towards the door the eighth part of a muhūrta, whether a guest is to be seen. He should honour the guest, who has arrived there, with rice and other food and with water and with fragrant flowers and other presents, according to his power. He should not treat as a guest a friend, nor a fellow-villager, nor one who bears the name of an unknown family, nor one who has arrived at that time. Men call a brāhman who has arrived, hungry, wearied, supplicating, indigent, a guest; he should be honoured by the wise according to their power. A learned man should not inquire his lineage or conduct, nor his private study; he should esteem him, whether handsome or unhandsome in appearance, as a prajāpati. For since he stays but a transitory time, he is therefore called an atithi, ‘a guest.’ When he is satisfied, the gṛhastha is released from the debt which arises from hospitality. The guilty man, who without giving to the guest himself eats, he incurs only sin and feeds on ordure in another life. The guest transferring his misdeeds to that man, from whose house he turns Back with Broken hopes, and taking that man’s merit, goes off. Moreover a man should honour a guest respectfully according to his power with gifts of water and vegetables, or with just what he is himself eating.

“And he should daily perform the śrāddha with rice and other food and with water with regard to the pitṛs and brāhmans; or he should feed a brāhman. Taking up an agra[8] of the rice, he should present it to a brāhman: and he should give an alms to wandering brahmans who ask. The alms should be the size of a mouthful, the agra four mouthfuls. Brāhmans call the agra four times a hantakāra[9] But without giving food, or a hantakāra, an agra or an alms, according to his substance, he must not himself eat. And he should eat, after he has done reverence to guests, friends, paternal kinsmen, relatives, and petitioners, the maimed, and children and old men and the sick.

“If a man consumed with hunger, or another who is destitute wants food, he should be fed by a householder who has adequate[10] substance. Whatever kinsman is dispirited when he reaches a prosperous kinsman, the latter gets the sin that has been done by the dispirited man. And the precept must be observed at evening, and he should do reverence to the guest who has arrived there after sunset, accordingly to his ability, with a bed, a seat and food.

“Thus a weight is placed on the shoulder of one who undertakes family life. Vidhātṛ, and the gods, and the pitṛs, the great Ṛṣis, all shower bliss on him, and so also do guests and relatives: and the herds of cattle and the flocks of birds, and the minute insects that exist besides, are satisfied.

And Atri himself used to sing songs on this subject, noble one! Hear those, O noble one! that appertain to the gṛhastha period—‘Having done reverence to the gods, and the pitṛs and guests, relatives likewise, and female relations, and, gurus also, the gṛhastha who has substance should scatter the fragments on the ground for both dogs and low caste men and birds: for he should certainly perform this offering to the Viśvadevas evening and day. And he should not himself eat flesh, rice and vegetables and whatever may have been prepared in the house, which he may not scatter according to the precept.’”

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

The oblation to the gods.

[2]:

The oblation to the pitṛs.

[3]:

Read tasyāḥ for tasyā,

[4]:

Darkness.

[5]:

Complete darkness.

[6]:

Deep gloom.

[7]:

Read mānavaḥ for mānavāḥ.

[8]:

A measure.

[9]:

A formula of salutation, or an offering to a guest.

[10]:

Head samarthe for samartho?