Mahabharata (English)

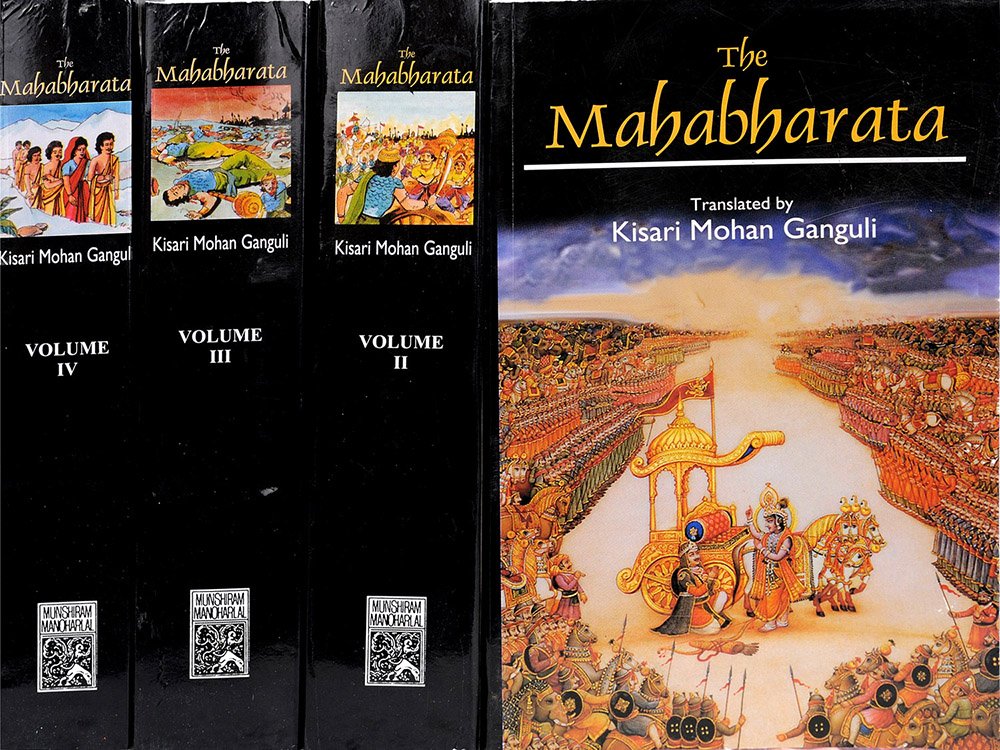

by Kisari Mohan Ganguli | 2,566,952 words | ISBN-10: 8121505933

The English translation of the Mahabharata is a large text describing ancient India. It is authored by Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa and contains the records of ancient humans. Also, it documents the fate of the Kauravas and the Pandavas family. Another part of the large contents, deal with many philosophical dialogues such as the goals of life. Book...

Section XXXIII

'Vaisampayana said, "Hearing these words of Yajnaseni, Bhimasena, sighing in wrath, approached the king and addressed him, saying,

'Walk, O monarch, in the customary path trodden by good men, (before you) in respect of kingdoms. What do we gain by living in the asylum of ascetics, thus deprived of virtue, pleasure, and profit? It is not by virtue, nor by honesty, nor by might, but by unfair dice, that our kingdom has been snatched by Duryodhana. Like a weak offal-eating jackal snatching the prey from mighty lions, he has snatched away our kingdom.

Why, O monarch, in obedience to the trite merit of sticking to a promise, dost you suffer such distress, abandoning that wealth which is the source of both virtue and enjoyments? It was for your carelessness, O king, that our kingdom protected by the wielder of the Gandiva and therefore, incapable of being wrested by Indra himself, was snatched from us in our very sight. It was for you, O monarch, that, ourselves living, our prosperity was snatched away from us like a fruit from one unable to use his arms, or like kine from one incapable of using his legs.

You are faithful in the acquisition of virtue. It was to please you, O Bharata, that we have suffered ourselves to be overwhelmed with such dire calamity. O bull of the Bharata race, it was because we were subject to your control that we are thus tearing the hearts of our friends and gratifying our foes. That we did not, in obedience to you, even then slay the sons of Dhritarashtra, is an act of folly on our part that grieves me sorely.

This your abode, O king, in the woods, like that of any wild animal, is what a man of weakness alone would submit to. Surely, no man of might would ever lead such a life. This your course of life is approved neither by Krishna, nor Vibhatsu, nor by Abhimanyu, nor by the Srinjayas, nor by myself, nor by the sons of Madri. Afflicted with the vows, your cry is Religion! Religion! Hast you from despair been deprived of your manliness?

Cowards alone, unable to win back their prosperity, cherish despair, which is fruitless and destructive of one’s purposes. You have ability and eyes. You seest that manliness dwells in us. It is because you have adopted a life of peace that you feelest not this distress. These Dhritarashtras regard us who are forgiving, as really incompetent. This, O king, grieves me more than death in battle. If we all die in fair fight without turning our backs on the foe, even that would be better than this exile, for then we should obtain regions of bliss in the other world.

Or, if, O bull of the Bharata race, having slain them all, we acquire the entire earth, that would be prosperity worth the trial. We who ever adhere to the customs of our order, who ever desire grand achievements, who wish to avenge our wrongs, have this for our bounden duty. Our kingdom wrested from us, if we engage in battle, our deeds when known to the world will procure for us fame and not slander. And that virtue, O king, which tortures one’s own self and friends, is really no virtue. It is rather vice, producing calamities. Virtue is sometimes also the weakness of men. And though such a man might ever be engaged in the practice of virtue, yet both virtue and profit forsake him, like pleasure and pain forsaking a person that is dead.

He that practises virtue for virtue’s sake always suffers. He can scarcely be called a wise man, for he knows not the purposes of virtue like a blind man incapable of perceiving the solar light. He that regards his wealth to exist for himself alone, scarcely understands the purposes of wealth. He is really like a servant that tends kine in a forest. He again that pursues wealth too much without pursuing virtue and enjoyments, deserves to be censured and slain by all men. He also that ever pursues enjoyments without pursuing virtue and wealth, loses his friends and virtue and wealth also.

Destitute of virtue and wealth such a man, indulging in pleasure at will, at the expiration of his period of indulgence, meets with certain death, like a fish when the water in which it lives has been dried up. It is for these reasons that they that are wise are ever careful of both virtue and wealth, for a union of virtue and wealth is the essential requisite of pleasure, as fuel is the essential requisite of fire. Pleasure has always virtue for its root, and virtue also is united with pleasure.

Know, O monarch, that both are dependent on each other like the ocean and the clouds, the ocean causing the clouds and the clouds filling the ocean. The joy that one feels in consequence of contact with objects of touch or of possession of wealth, is what is called pleasure. It exists in the mind, having no corporeal existence that one can see. He that wishes (to obtain) wealth, seeks for a large share of virtue to crown his wish with success. He that wishes for pleasure, seeks wealth, (so that his wish may be realised).

Pleasure however, yields nothing in its turn. One pleasure cannot lead to another, being its own fruit, as ashes may be had from wood, but nothing from those ashes in their turn. And, O king, as a fowler kills the birds we see, so does sin slay the creatures of the world. He, therefore, who misled by pleasure or covetousness, beholds not the nature of virtue, deserves to be slain by all, and becomes wretched both here and here-after.

It is evident, O king, that you knowest that pleasure may be derived from the possession of various objects of enjoyment. You also well knowest their ordinary states, as well as the great changes they undergo. At their loss or disappearance occasioned by decrepitude or death, arises what is called distress. That distress, O king, has now overtaken us. The joy that arises from the five senses, the intellect and the heart, being directed to the objects proper to each, is called pleasure. That pleasure, O king, is, as I think, one of the best fruits of our actions.

"Thus, O monarch, one should regard virtue, wealth and pleasure one after another. One should not devote one self to virtue alone, nor regard wealth as the highest object of one’s wishes, nor pleasure, but should ever pursue all three. The scriptures ordain that one should seek virtue in the morning, wealth at noon, and pleasure in the evening. The scriptures also ordain that one should seek pleasure in the first portion of life, wealth in the second, and virtue in the last.

And, O you foremost of speakers, they that are wise and fully conversant with proper division of time, pursue all three, virtue, wealth, and pleasure, dividing their time duly. O son of the Kuru race, whether independence of these (three), or their possession is the better for those that desire happiness, should be settled by you after careful thought.

And you should then, O king, unhesitatingly act either for acquiring them, or abandoning them all. For he who lives wavering between the two doubtingly, leads a wretched life. It is well known that your behaviour is ever regulated by virtue. Knowing this your friends counsel you to act. Gift, sacrifice, respect for the wise, study of the Vedas, and honesty, these, O king, constitute the highest virtue and are efficacious both here and hereafter. These virtues, however, cannot be attained by one that has no wealth, even if, O tiger among men, he may have infinite other accomplishments. The whole universe, O king, depends upon virtue. There is nothing higher than virtue.

And virtue, O king, is attainable by one that has plenty of wealth. Wealth cannot be earned by leading a mendicant life, nor by a life of feebleness. Wealth, however, can be earned by intelligence directed by virtue. In your case, O king, begging, which is successful with Brahmanas, has been forbidden. Therefore, O bull amongst men, strive for the acquisition of wealth by exerting your might and energy. Neither mendicancy, nor the life of a Sudra is what is proper for you. Might and energy constitute the virtue of the Kshatriya in especial. Adopt you, therefore, the virtue of your order and slay the enemies.

Destroy the might of Dhritarashtra’s sons, O son of Pritha, with my and Arjuna’s aid. They that are learned and wise say that sovereignty is virtue. Acquire sovereignty, therefore, for it behoves you not to live in a state of inferiority. Awake, O king, and understand the eternal virtues (of the order). By birth you belongest to an order whose deeds are cruel and are a source of pain to man. Cherish your subjects and reap the fruit thereof. That can never be a reproach.

Even this, O king, is the virtue ordained by God himself for the order to which you belongest! If you tallest away therefrom, you will make thyself ridiculous. Deviation from the virtues of one’s own order is never applauded. Therefore, O you of the Kuru race, making your heart what it ought to be, agreeably to the order to which you belongest, and casting away this course of feebleness, summon your energy and bear your weight like one that bears it manfully.

No king, O monarch, could ever acquire the sovereignty of the earth or prosperity or affluence by means of virtue alone. Like a fowler earning his food in the shape of swarms of little easily-tempted game, by offering them some attractive food, does one that is intelligent acquire a kingdom, by offering bribes unto low and covetous enemies. Behold, O bull among kings, the Asuras, though elder brothers in possession of power and affluence, were all vanquished by the gods through stratagem. Thus, O king, everything belongs to those that are mighty.

And, O mighty-armed one, slay your foes, having recourse to stratagem. There is none equal unto Arjuna in wielding the bow in battle. Nor is there anybody that may be equal unto me in wielding the mace. Strong men, O monarch, engage in battle depending on their might, and not on the force of numbers nor on information of the enemy’s plans procured through spies.

Therefore, O son of Pandu exert your might. Might is the root of wealth. Whatever else is said to be its root is really not such. As the shade of the tree in winter goes for nothing, so without might everything else becomes fruitless. Wealth should be spent by one who wishes to increase his wealth, after the manner, O son of Kunti, of scattering seeds on the ground. Let there be no doubt then in your mind. Where, however, wealth that is more or even equal is not to be gained, there should be no expenditure of wealth. For investment of wealth are like the ass, scratching, pleasurable at first but painful afterwards.

Thus, O king of men, the person who throws away like seeds a little of his virtue in order to gain a larger measure of virtue, is regarded as wise. Beyond doubt, it is as I say. They that are wise alienate the friends of the foe that owns such, and having weakened him by causing those friends to abandon him thus, they then reduce him to subjection. Even they that are strong, engage in battle depending on their courage. One cannot by even continued efforts (uninspired by courage) or by the arts of conciliation, always conquer a kingdom.

Sometimes, O king, men that are weak, uniting in large numbers, slay even a powerful foe, like bees killing the despoiler of the honey by force of numbers alone. (As regards thyself), O king, like the sun that sustains as well as slays creatures by his rays, adopt you the ways of the sun. To protect one’s kingdom and cherish the people duly, as done by our ancestors, O king, is, it has been heard by us, a kind of asceticism mentioned even in the Vedas. By ascetism, O king, a Kshatriya cannot acquire such regions of blessedness as he can by fair fight whether ending in victory or defeat.

Beholding, O king, this your distress, the world has come to the conclusion that light may forsake the Sun and grace the Moon. And, O king, good men separately as well as assembling together, converse with one another, applauding you and blaming the other. There is this, moreover, O monarch, viz., that both the Kurus and the Brahmanas, assembling together, gladly speak of your firm adherence to truth, in that you have never, from ignorance, from meanness, from covetousness, or from fear, uttered an untruth.

Whatever sin, O monarch, a king commits in acquiring dominion, he consumes it all afterwards by means of sacrifices distinguished by large gifts. Like the Moon emerging from the clouds, the king is purified from all sins by bestowing villages on Brahmanas and kine by thousands. Almost all the citizens as well as the inhabitants of the country, young or old, O son of the Kuru race, praise you, O Yudhishthira! This also, O Bharata, the people are saying amongst themselves, viz., that as milk in a bag of dog’s hide, as the Vedas in a Sudra, as truth in a robber, as strength in a woman, so is sovereignty in Duryodhana. Even women and children are repeating this, as if it were a lesson they seek to commit to memory.

O represser of foes, you have fallen into this state along with ourselves. Alas, we also are lost with you for this calamity of thine. Therefore, ascending in your car furnished with every implement, and making the superior Brahmanas utter benedictions on you, march you with speed, even this very day, upon Hastinapura, in order that you mayst be able to give unto Brahmanas the spoils of victory. Surrounded by your brothers, who are firm wielders of the bow, and by heroes skilled in weapons and like unto snakes of virulent poison, set you out even like the slayer Vritra surounded by the Marutas.

And, O son of Kunti, as you are powerful, grind you with your might your weak enemies, like Indra grinding the Asuras; and snatch you from Dhritarashtra’s son the prosperity he enjoys. There is no mortal that can bear the touch of the shafts furnished with the feathers of the vulture and resembling snakes of virulent poison, that would be shot from the Gandiva.

And, O Bharata, there is not a warrior, nor an elephant, nor a horse, that is able to bear the impetus of my mace when I am angry in battle. Why, O son of Kunti, should we not wrest our kingdom from the foe, fighting with the aid of the Srinjayas and Kaikeyas, and the bull of the Vrishni race? Why, O king, should we not succeed in wresting the (sovereignty of the) earth that is now in the hands of the foe, if, aided by a large force, we do but strive?"

Conclusion:

This concludes Section XXXIII of Book 3 (Vana Parva) of the Mahabharata, of which an English translation is presented on this page. This book is famous as one of the Itihasa, similair in content to the eighteen Puranas. Book 3 is one of the eighteen books comprising roughly 100,000 Sanskrit metrical verses.

FAQ (frequently asked questions):

Which keywords occur in Section XXXIII of Book 3 of the Mahabharata?

The most relevant definitions are: Bharata, Brahmanas, Dhritarashtra, Kuru, Kunti, Vedas; since these occur the most in Book 3, Section XXXIII. There are a total of 30 unique keywords found in this section mentioned 56 times.

What is the name of the Parva containing Section XXXIII of Book 3?

Section XXXIII is part of the Arjunabhigamana Parva which itself is a sub-section of Book 3 (Vana Parva). The Arjunabhigamana Parva contains a total of 26 sections while Book 3 contains a total of 13 such Parvas.

Can I buy a print edition of Section XXXIII as contained in Book 3?

Yes! The print edition of the Mahabharata contains the English translation of Section XXXIII of Book 3 and can be bought on the main page. The author is Kisari Mohan Ganguli and the latest edition (including Section XXXIII) is from 2012.