Mahabharata (English)

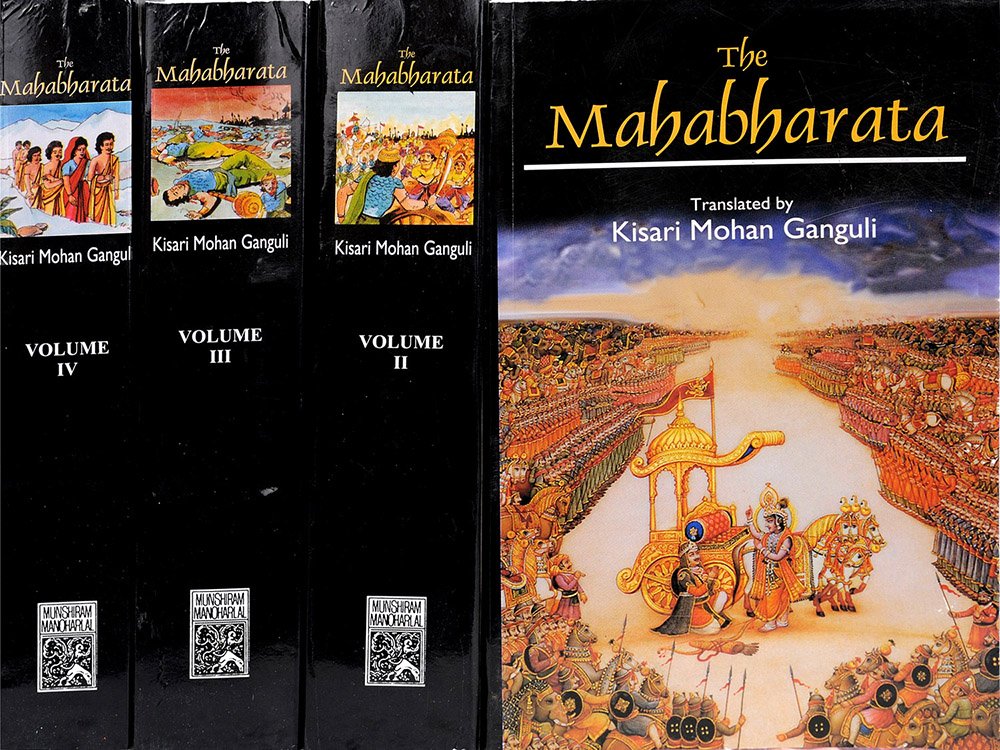

by Kisari Mohan Ganguli | 2,566,952 words | ISBN-10: 8121505933

The English translation of the Mahabharata is a large text describing ancient India. It is authored by Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa and contains the records of ancient humans. Also, it documents the fate of the Kauravas and the Pandavas family. Another part of the large contents, deal with many philosophical dialogues such as the goals of life. Book...

Section XII

"Yudhishthira said, 'It behoves, O king to tell me truly which of the two viz., man or woman derives the greater pleasure from an act of union with each other. Kindly resolve my doubt in this respect."

"Bhishma said, 'In this connection is cited this old narrative of the discourse between Bhangasvana and Sakra as a precedent illustrating the question. In days of yore there lived a king of the name of Bhangasvana. He was exceedingly righteous and was known as a royal sage. He was, however, childless, O chief of man, and therefore performed a sacrifice from desire of obtaining an issue. The sacrifice which that mighty monarch performed was the Agnishtuta. In consequence of the fact that the deity of fire is alone adored in that sacrifice, this is always disliked by Indra. Yet it is the sacrifice that is desired by men when for the purpose of obtaining an issue they seek to cleanse themselves of their sins.[1] The highly blessed chief of the celestials, viz. Indra, learning that the monarch was desirous of performing the Agnishtuta, began from that moment to look for the laches of that royal sage of well-restrained soul (for if he could succeed in finding some laches, he could then punish his disregarder). Notwithstanding all his vigilance, however, O king, Indra failed to detect any laches, on the part of the high-souled monarch. Some time after, one day, the king went on a hunting expedition. Saying unto himself—This, indeed, is an opportunity,—Indra stupefied the monarch. The king proceeded alone on his horse, confounded because of the chief of the celestials having stupefied his senses. Afflicted with hunger and thirst, the king’s confusion was so great that he could not ascertain the points of the compass. Indeed, afflicted with thirst, he began to wander hither and thither. He then beheld a lake that was exceedingly beautiful and was full of transparent water. Alighting from his steed, and plunging into the lake, he caused his animal to drink. Tying his horse then, whose thirst had been slaked, to a tree, the king plunged into the lake again for performing his ablutions. To his amazement he found that he was changed, by virtue of the waters, into a woman. Beholding himself thus transformed in respect of sex itself, the king became overpowered with shame. With his senses and mind completely agitated, he began to reflect with his whole heart in this strain:—Alas, how shall I ride my steed? How shall I return to my capital? In consequence of the Agnishtuta sacrifice I have got a hundred sons all endued with great might, and all children of my own loins. Alas, thus transformed, what shall I say unto them? What shall I say unto my spouses, my relatives and well-wishers, and my subjects of the city and the provinces? Rishis conversant with the truths of duty and religion and other matters say that mildness and softness and liability to extreme agitation are the attributes of women, and that activity, hardness, and energy are the attributes of men. Alas, my manliness has disappeared. For what reason has femininity come over me? In consequence of this transformation of sex, how shall I succeed in mounting my horse again?—Having indulged in these sad thoughts, the monarch, with great exertion, mounted his steed and came back to his capital, transformed though he had been into a woman. His sons and spouses and servants, and his subjects of the city and the provinces, beholding that extraordinary transformation, became exceedingly amazed. Then that royal sage, that foremost of eloquent men, addressing them all, said,—I had gone out on a hunting expedition, accompanied by a large force. Losing all knowledge of the points of the compass, I entered a thick and terrible forest, impelled by the fates. In that terrible forest, I became afflicted with thirst and lost my senses. I then beheld a beautiful lake abounding with fowl of every description. Plunging into that stream for performing my ablutions, I was transformed into a woman!—Summoning then his spouses and counsellors, and all his sons by their names, that best of monarchs transformed into a woman said unto them these words:—Do you enjoy this kingdom in happiness. As regards myself, I shall repair to the woods, you sons.—Having said so unto his children, the monarch proceeded to the forest. Arrived there, she came upon an asylum inhabited by an ascetic. By that ascetic the transformed monarch gave birth to a century of sons. Taking all those children of hers, she repaired to where her former children were, and addressing the latter, said,—You are the children of my loins while I was a man. These are my children brought forth by me in this state of transformation. You sons, do you all enjoy my kingdom together, like brothers born of the same parents.—At this command of their parent, all the brothers, uniting together, began to enjoy the kingdom as their joint property. Beholding those children of the king all jointly enjoying the kingdom as brothers born of the same parents, the chief of the celestials, filled with wrath, began to reflect—By transforming this royal sage into a woman I have, it seems, done him good instead of an injury. Saying this, the chief of the celestials viz., Indra of a hundred sacrifices, assuming the form of a Brahmana, repaired to the capital of the king and meeting all the children succeeded in disuniting the princes. He said unto them—Brothers never remain at peace even when they happen to be the children of the same father. The sons of the sage Kasyapa, viz., the deities and the Asuras, quarrelled with each other on account of the sovereignty of the three worlds. As regards you princes, you are the children of the royal sage Bhangasvana. These others are the children of an ascetic. The deities and the Asuras are children of even one common sire, and yet the latter quarrelled with each other. How much more, therefore, should you quarrel with each other? This kingdom that is your paternal property is being enjoyed by these children of an ascetic. With these words, Indra succeeded in causing a breach between them, so that they were very soon engaged in battle and slew each other. Hearing this, king Bhangasvana, who was living as an ascetic woman, burnt with grief and poured forth her lamentations. The lord of the celestials viz. Indra, assuming the guise of a Brahmana, came to that spot where the ascetic lady was living and meeting her, said,—O you that art possessed of a beautiful face, with what grief dost you burn so that you are pouring forth your lamentations?—Beholding the Brahmana the lady told him in a piteous voice,—Two hundred sons of mine O regenerate one, have been slain by Time. I was formerly a king, O learned Brahmana and in that state had a hundred sons. These were begotten by me after my own form, O best of regenerate persons. On one occasion I went on a hunting expedition. Stupefied, I wandered amidst a thick forest. Beholding at last a lake, I plunged into it. Rising, O foremost of Brahmanas, I found that I had become a woman. Returning to my capital I installed my sons in the sovereignty of my dominions and then departed for the forest. Transformed into a woman, I bore a hundred sons to my husband who is a high souled ascetic. All of them were born in the ascetic’s retreat. I took them to the capital. My children, through the influence of Time, quarrelled with each other, O twice-born one. Thus afflicted by Destiny, I am indulging in grief. Indra addressed him in these harsh words.—In former days, O lady, you gayest me great pain, for you didst perform a sacrifice that is disliked by Indra. Indeed, though I was present, you didst not invoke me with honours. I am that Indra, O you of wicked understanding. It is I with whom you have purposely sought hostilities. Beholding Indra, the royal sage fell at his feet, touching them with his head, and said,—Be gratified with me, O foremost of deities. The sacrifice of which you speakest was performed from desire of offspring (and not from any wish to hurt you). It behoves you therefore, to grant me your pardon.—Indra, seeing the transformed monarch prostrate himself thus unto him, became gratified with him and desired to give him a boon. Which of your sons, O king, dost you wish, should revive, those that were brought forth by you transformed into a woman, or those that were begotten by you in your condition as a person of the male sex? The ascetic lady, joining her hands, answered Indra, saying, O Vasava, let those sons of mine come to life that were borne by me as a woman. Filled with wonder at this reply, Indra once more asked the lady, Why dost you entertain less affection for those children of thine that were begotten by you in your form of a person of the male sex? Why is it that you bearest greater affection for those children that were borne by you in your transformed state? I wish to hear the reason of this difference in respect of your affection. It behoves you to tell me everything.'

"The lady said, 'The affection that is entertained by a woman is much greater than that which is entertained by a man. Hence, it is, O Sakra, that I wish those children to come back to life that were borne by me as a woman.'

"Bhishma continued, 'Thus addressed, Indra became highly pleased and said unto her, O lady that art so truthful, let all your children come back into life. Do you take another boon, O foremost of kings, in fact, whatever boon you likest. O you of excellent vows, do you take from me whatever status you choosest, that of woman or of man.'

"The lady said, 'I desire to remain a woman, O Sakra. In fact,—do not wish to be restored to the status of manhood, O Vasava.—Hearing this answer, Indra once more asked her, saying,—Why is it, O puissant one, that abandoning the status of manhood you wishest that of womanhood? Questioned thus, that foremost of monarchs transformed into a woman answered, 'In acts of congress, the pleasure that women enjoy is always much greater than what is enjoyed by men. It is for this reason, O Sakra, that I desire to continue a woman; O foremost of the deities, truly do I say unto you that I derive greater pleasure in my present status of womanhood. I am quite content with this status of womanhood that I now have. Do you leave me now, O lord of heaven.—Hearing these words of hers, the lord of the celestials answered,—So be it,—and bidding her farewell, proceeded to heaven. Thus, O monarch, it is known that woman derives much greater pleasure than man under the circumstances you have asked.'"

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

The belief is that a man remains childless in consequence of his sins. If these sins can be washed away, he may be sure to obtain children.

Conclusion:

This concludes Section XII of Book 13 (Anushasana Parva) of the Mahabharata, of which an English translation is presented on this page. This book is famous as one of the Itihasa, similair in content to the eighteen Puranas. Book 13 is one of the eighteen books comprising roughly 100,000 Sanskrit metrical verses.