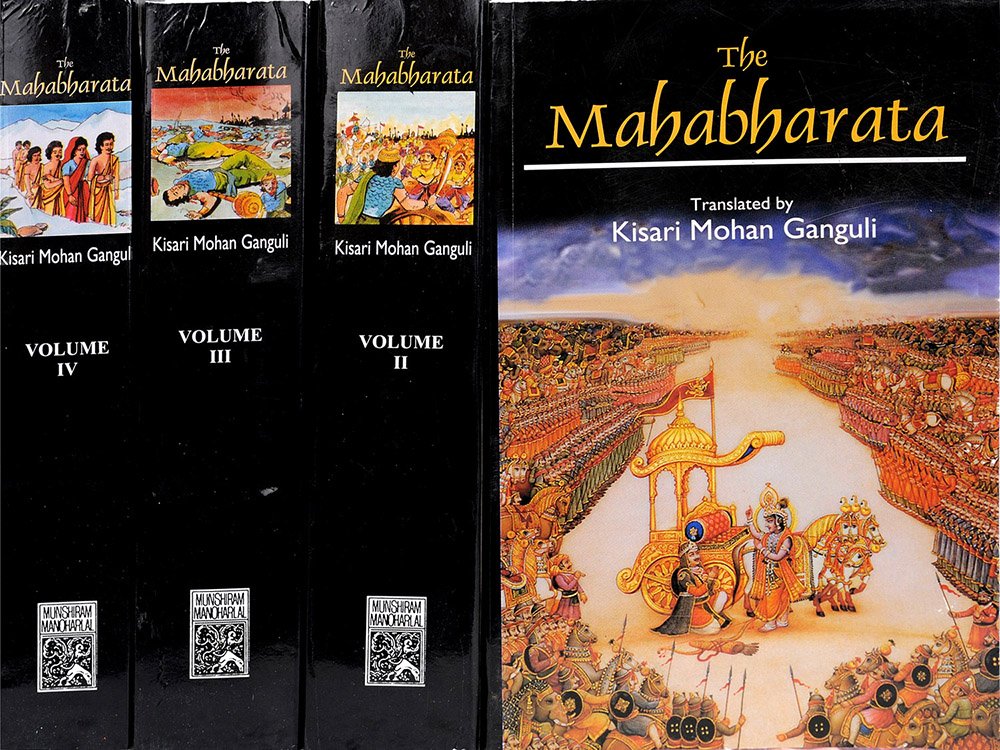

Mahabharata (English)

by Kisari Mohan Ganguli | 2,566,952 words | ISBN-10: 8121505933

The English translation of the Mahabharata is a large text describing ancient India. It is authored by Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa and contains the records of ancient humans. Also, it documents the fate of the Kauravas and the Pandavas family. Another part of the large contents, deal with many philosophical dialogues such as the goals of life. Book...

Section CCCLX

"The Naga said, 'O you of sweet smiles, for whom hast you taken that Brahmana? Is he really a human being or is he some deity that has come hither in the disguise of a Brahmana? O you of great fame, who is there among human beings that would be desirous of seeing me or that would be competent for the purpose? Can a human being, desiring to see me, leave such a command with you about dispatching me to him for paying him a visit at the place where he is dwelling? Amongst the deities and Asuras and celestial Rishis, O amiable lady, the Nagas are endued with great energy. Possessed of great speed, they are endued again with excellent fragrance. They deserve to be worshipped. They are capable of granting boons. Indeed, we too deserve to be followed by others in our train. I tell you, O lady, that we are incapable of being seen by human beings.'[1]

"The spouse of the Naga chief said, 'Judging by his simplicity and candour I know that that Brahmana is not any deity who subsists on air. O you of great wrath, I also know this, viz., that he reveres you with all his heart. His heart is set upon the accomplishment of some object that depends upon your aid. As the bird called Chataka, which is fond of rain, waits in earnest expectation of a shower (for slaking its thirst), even so is that Brahmana waiting in expectation of a meeting with you.[2] Let no calamity betake him in consequence of his inability to obtain a sight of you. No person born like you in a respectable family can be regarded to remain respectable by neglecting a guest arrived at his house.[3] Casting off that wrath which is natural to you, it behoves you to go and see that Brahmana. It behoves you not to suffer thyself to be consumed by disappointing that Brahmana. The king or the prince, by refusing to wipe the tears of persons that come to him from hopes of relief, incurs the sin of foeticide. By abstaining from speech one attains to wisdom. By practising gifts one acquires great fame. By adhering to truthfulness of speech, one acquires the gift of eloquence and comes to be honoured in heaven. By giving away land one attains to that high end which is ordained for Rishis leading the sacred mode of life. By earning wealth through righteous means, one succeeds in attaining to many desirable fruits. By doing in its entirety what is beneficial for oneself, one can avoid going to hell. That is what the righteous say.

"The Naga said, 'I had no arrogance due to pride. In consequence, however, of my birth, the measure of my arrogance was considerable. Of wrath, which is born of desire, O blessed lady, I have none. It has all been consumed by the fire of your excellent instructions. I do not behold, O blessed dame, any darkness that is thicker than wrath. In consequence, however, of the Naga having excess of wrath, they have become object of reproach with all persons.[4] By succumbing to the influence of wrath, the ten-headed Ravana of great prowess, became the rival of Sakra and was for that reason slain by Rama in battle. Hearing that the Rishi Rama of Bhrigu’s race had entered the inner apartments of their palace for bringing away the calf of the Homa cow of their sire, the sons of Karttavirya, yielding to wrath, took such entry as an insult to their royal house, and as the consequence thereof, they met with destruction at the hands of Rama. Indeed, Karttavirya of great strength, resembling the Thousand-eyed Indra himself, in consequence of his having yielded to wrath, was slain in battle by Rama of Jamadagni’s race. Verily, O amiable lady at your words I have restrained my wrath, that foe of penances that destroyer of all that is beneficial for myself. I praise my own self greatly since, O large-eyed one, I am fortunate enough to own you for my wife,—you that are possessed of every virtue and that hast inexhaustible merits. I shall now proceed to that spot where the Brahmana is staying. I shall certainly address that Brahmana in proper words and he shall certainly go hence, his wishes being accomplished."

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

The meaning of annyayinah is that we should be followed by others, i.e., we deserve to walk at the head of others.

[2]:

The Indian bird Chataka has a natural hole on the upper part of its long neck in consequence of which it is seen to always sit with beaks upturned, so that the upper part of the neck keeps the hole covered. The Chataka is incapable of slaking its thirst in a lake or river, for it cannot bend its neck down. Rain water is what it must drink. Its cry is shrill and sharp but not without sweetness. 'Phate-e-ek-jal' is supposed to be the cry uttered by it. When the Chataka cries, the hearers expect rain. Eager expectation with respect to anything is always compared to the Chataka’s expectation of rain water.

[3]:

[4]:

It is a pity that even such verses have not been rendered correctly by the Burdwan translator. K. P. Singha gives the sense correctly, but the translation is not accurate.

Conclusion:

This concludes Section CCCLX of Book 12 (Shanti Parva) of the Mahabharata, of which an English translation is presented on this page. This book is famous as one of the Itihasa, similair in content to the eighteen Puranas. Book 12 is one of the eighteen books comprising roughly 100,000 Sanskrit metrical verses.