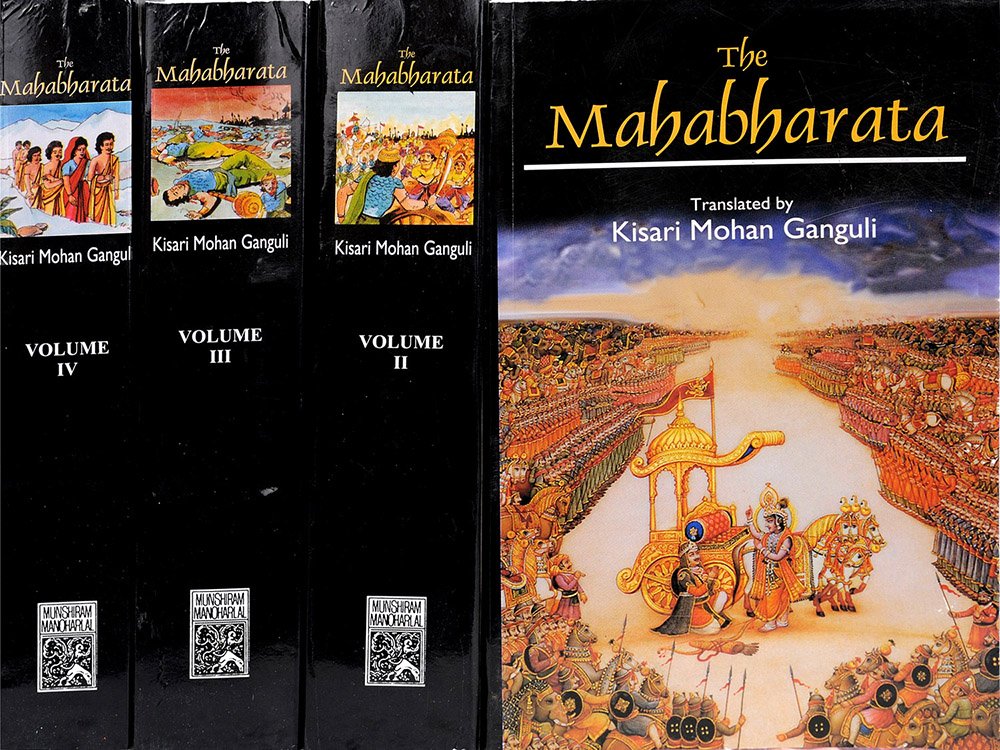

Mahabharata (English)

by Kisari Mohan Ganguli | 2,566,952 words | ISBN-10: 8121505933

The English translation of the Mahabharata is a large text describing ancient India. It is authored by Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa and contains the records of ancient humans. Also, it documents the fate of the Kauravas and the Pandavas family. Another part of the large contents, deal with many philosophical dialogues such as the goals of life. Book...

Section CCL

"Suka said, 'Let your reverence tell me of that which is the foremost of all duties, indeed, of that duty above which no higher one exists in this world.'

"Vyasa said, 'I shall now tell you of duties having a very ancient origin and laid down by the Rishis, duties that are distinguished above all others. Listen to me with undivided attention. The senses that are maddening should carefully be restrained by the understanding like a sire restraining his own inexperienced children liable to fall into diverse evil habits. The withdrawal of the mind and the senses from all unworthy objects and their due concentration (upon worthy objects) is the highest penance. That is the foremost of all duties. Indeed, that is said to be the highest duty. Directing, by the aid of the understanding, the senses having the mind for their sixth, and without, indeed, thinking of worldly objects which have the virtue of inspiring innumerable kinds of thought, one should live contented with one’s own self. When the senses and the mind, withdrawn from the pastures among which they usually run loose, come back for residing in their proper abode, it is then that you will behold in your own self the Eternal and Supreme Soul.[1] Those high-souled Brahmanas that are possessed of wisdom succeed in beholding that Supreme and Universal Soul which is like unto a blazing fire in effulgence. As a large tree endued with numerous branches and possessed of many flowers and fruits does not know in which part it has flowers and in which it has fruits, after the same manner the Soul as modified by birth and other attributes, does not know whence it has come and whither it is to go. There is, however, an inner Soul, which beholds (knows) everything.[2] One sees the Soul oneself with the aid of the lighted lamp of knowledge. Beholding, therefore, thyself with your own self, cease to regard your body as thyself and attain you to omniscience. Cleansed of all sins, like unto a snake that has cast off its slough, one attains to high intelligence here and becomes free from every anxiety and the obligation of acquiring a new body (in a subsequent birth). Its current spreading in diverse directions, frightful is this river of life bearing the world onward in its course. The five senses are its crocodiles. The mind and its purposes are the shores. Cupidity and stupefaction of judgment are the grass and straw that float on it, covering its bosom. Lust and wrath are the fierce reptiles that live in it. Truth forms the tirtha by its miry banks. Falsehood forms its surges, anger its mire. Taking its rise from the Unmanifest, rapid is its current, and incapable of being crossed by persons of uncleansed souls. Do you, with the aid of the understanding cross that river having desires for its alligators. The world and its concerns constitute the ocean towards which that river runs. Genus and species constitute its unfathomable depth that none can understand. One’s birth, O child, is the source from which that stream takes its rise. Speech constitutes its eddies. Difficult to cross, only men of learning and wisdom and understanding succeed in crossing it. Crossing it, you will succeed in freeing thyself from every attachment, acquiring a tranquil heart, knowing the Soul, and becoming pure in every respect. Relying them on a purged and elevated understanding, you will succeed in becoming Brahma’s self. Having dissociated thyself from every worldly attachment, having acquired a purified Soul and transcending every kind of sin, look you upon the world like a person looking from the mountain top upon creatures creeping below on the earth’s surface. Without giving way to wrath or joy, and without forming any cruel wish, you will succeed in beholding the origin and the destruction of all created objects. They that are endued with wisdom regard such an act to be the foremost of all things. Indeed, this act of crossing the river of life is regarded by the foremost of righteous persons, by ascetics conversant with the truth, to be the highest of all acts that one can accomplish. This knowledge of the all-pervading Soul is intended to be imparted to one’s son. It should be inculcated unto one that is of restrained senses, that is honest in behaviour, and that is docile or submissive. This knowledge of the Soul, of which I have just now spoken to you, O child, and the evidence of whose truth is furnished by the Soul itself, is a mystery,—indeed, the greatest of all mysteries, and the very highest knowledge that one can attain. Brahma has no sex,—male, female, or neuter. It is neither sorrow nor happiness. It has for its essence the past, the future, and the present. Whatever one’s sex, male or female, the person that attains to the knowledge of Brahma has never to undergo rebirth. This duty (of Yoga) has been inculcated for attaining to exemption from rebirth.[3] These words that I have used for answering your question lead to Emancipation in the same way as the diverse other opinions advanced by diverse other sages that have treated of this subject. I have expounded the topic to you after the manner in which it should be expounded. Those opinions sometimes become productive of fruit and sometimes not. (The words, however, that I have used are of a different kind, for these are sure to lead to success).[4] For this reason, O good child, a preceptor, when asked by a contented, meritorious, and self-restrained son or disciple, should, with a delighted heart, inculcate, according to their true import, these instructions that I have inculcated for the benefit of you, my son!'"

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Gocharaebhyah, literally, pastures, is used here to signify all external and internal objects upon which the senses and the mind are employed. Their proper home or abode is said to be Brahma.

[2]:

The absence of anything like precision in the language employed in such verses frequently causes confusion. The word atma as used in the first line is very indefinite. The commentator thinks it implies acetanabuddhi, i.e., the perishable understanding. I prefer, however, to take it as employed in the sense of Chit as modified by birth. It conies, I think, to the same thing in the end. The 'inner Soul' is, perhaps, the Soul or Chit as unmodified by birth and attributes.

[3]:

Abhavapratipattyartham is explained by the commentator as 'for the attainment of the unborn or the soul.'

Conclusion:

This concludes Section CCL of Book 12 (Shanti Parva) of the Mahabharata, of which an English translation is presented on this page. This book is famous as one of the Itihasa, similair in content to the eighteen Puranas. Book 12 is one of the eighteen books comprising roughly 100,000 Sanskrit metrical verses.