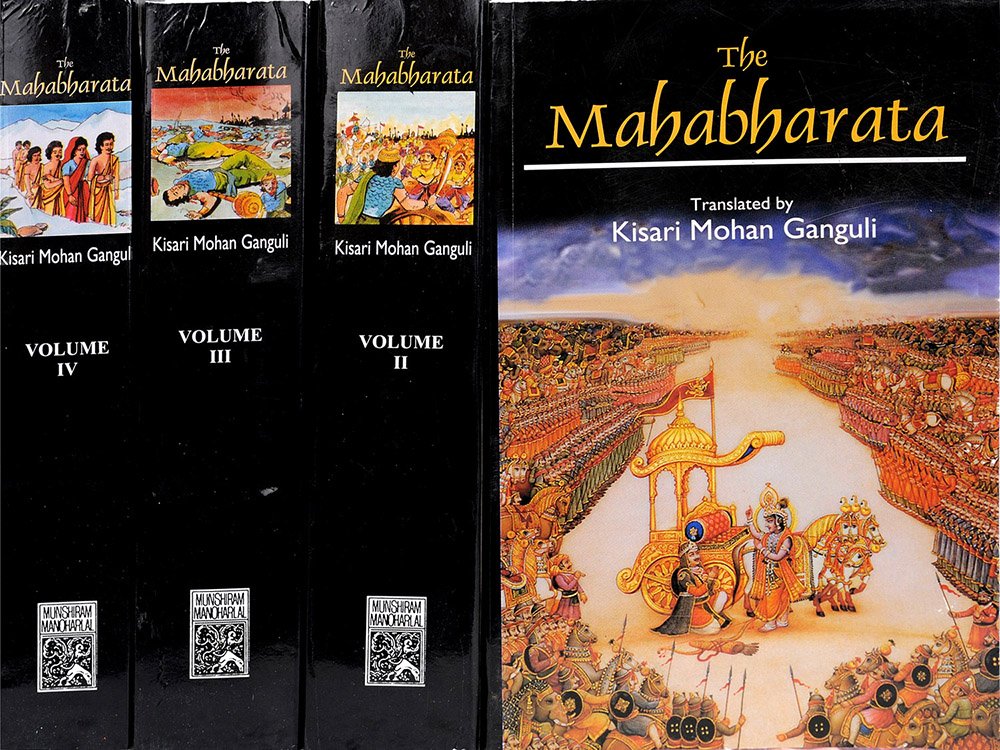

Mahabharata (English)

by Kisari Mohan Ganguli | 2,566,952 words | ISBN-10: 8121505933

The English translation of the Mahabharata is a large text describing ancient India. It is authored by Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa and contains the records of ancient humans. Also, it documents the fate of the Kauravas and the Pandavas family. Another part of the large contents, deal with many philosophical dialogues such as the goals of life. Book...

Section CLVI

"Bhishma continued, 'Having said these words unto the Salmali. that foremost of all persons conversant with Brahma, viz., Narada, represented unto the god of the wind all that the Salmali had said about him.'

"Narada said, 'There is a certain Salmali on the breast of Himavat, adorned with branches and leaves. His roots extend deep into the earth and his branches spread wide around. That tree, O god of the wind disregards you. He spoke many words fraught with abuse of thyself. It is not proper, O Wind, that I should repeat them in your hearing. I know, O Wind, that you are the foremost of all created things. I know too that you are a very superior and very mighty being, and that in wrath you resemblest the Destroyer himself.'

"Bhishma continued, 'Hearing these words of Narada, the god of wind, wending to that Salmali, addressed him in rage and said as follows.'

"The Wind-god said, 'O Salmali, you have spoken in derogation of me before Narada. Know that I am the god of the wind. I shall certainly show you my power and might. I know you well. You are no stranger to me. The puissant Grandsire, while engaged in creating the world, had for a time rested under you. It is in consequence of this incident that I have hitherto shown you grace. O worst of trees, it is for this that you standest unharmed, and not in consequence of your own might. You regardest me lightly as if I were a vulgar thing. I shall show myself unto you in such a way that you mayst not again disregard me.'

"Bhishma continued, 'Thus addressed, the Salmali laughed in derision and replied, saying, 'O god of the wind, you are angry with me. Do not forbear showing the extent of your might. Do you vomit all your wrath upon me. By giving way to your wrath, what will you do to me? Even if your might had, been your own (instead of being derived), I would not still have been afraid of you. I am superior to you in might. I should not be afraid of you. They are really strong in understanding. They, on the other hand, are not to be regarded strong that are possessed of only physical strength.' Thus addressed, the Wind-god said, 'Tomorrow I shall test your strength.' After this, night came. The Salmali, concluding mentally what the extent is of the Wind’s might and beholding his own self to be inferior to the god, began to say to himself, 'All that I said to Narada is false. I am certainly inferior in might to the Wind. Verity, he is strong in his strength. The Wind, as Narada said, is always mighty. Without doubt, I am weaker than other trees. But in intelligence no tree is my equal. Therefore, relying upon my intelligence I shall look at this fear that arises from the Wind. If the other trees in the forest all rely upon the same kind of intelligence, then, verily, no injury can result to them from the god of the Wind when he becomes angry. All of them. however, are destitute of understanding, and, therefore, they do not know, as I know, why or how the Wind succeeds in shaking and tearing them up.'"

Conclusion:

This concludes Section CLVI of Book 12 (Shanti Parva) of the Mahabharata, of which an English translation is presented on this page. This book is famous as one of the Itihasa, similair in content to the eighteen Puranas. Book 12 is one of the eighteen books comprising roughly 100,000 Sanskrit metrical verses.