Mahabharata (English)

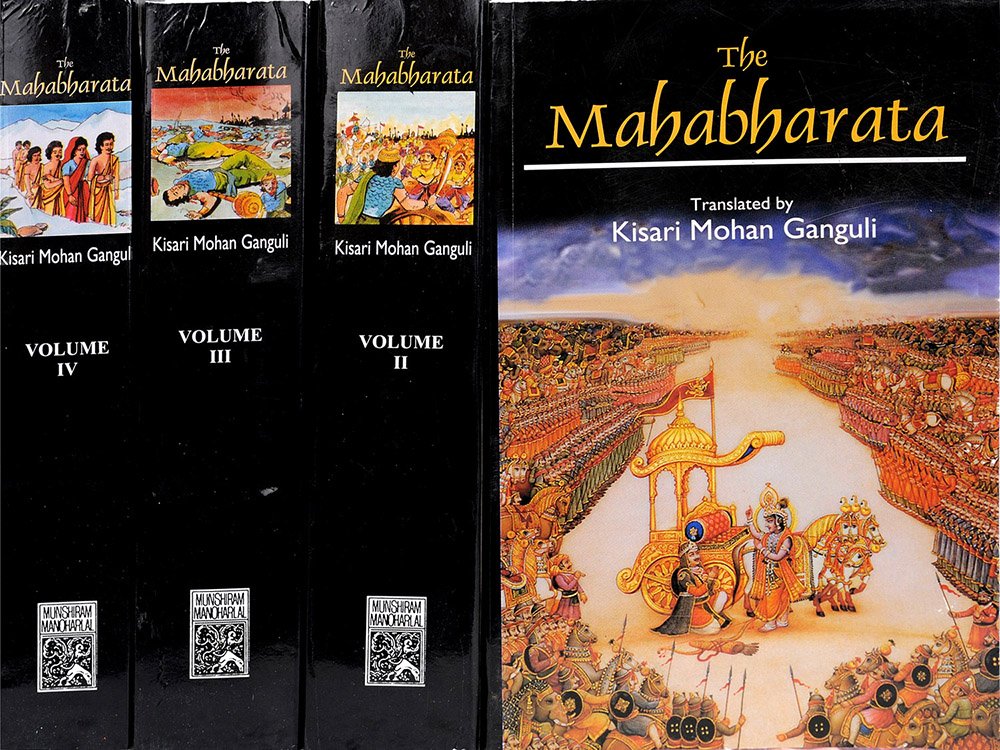

by Kisari Mohan Ganguli | 2,566,952 words | ISBN-10: 8121505933

The English translation of the Mahabharata is a large text describing ancient India. It is authored by Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa and contains the records of ancient humans. Also, it documents the fate of the Kauravas and the Pandavas family. Another part of the large contents, deal with many philosophical dialogues such as the goals of life. Book...

Section CCLVIII

Yudhishthira said,

"Why did that high-souled one give away a drona of corn? And, O eminently pious one, to whom and in what prescribed way did he give it? Do you tell me this. Surely, I consider the life of that virtuous person as having borne fruit with whose practices the possessor himself of the six attributes, witnessing everything, was well pleased."

"Vyasa said,

'There lived, O king, in Kurukshetra a virtuous man (sage), Mudgala by name. And he was truthful, and free from malice, and of subdued senses. And he used to lead the Sila and Uncha modes of life.[1] And although living like a pigeon, yet that one of mighty austerities entertained his guests, celebrated the sacrifice called Istikrita, and performed other rites. And that sage together with his son and wife, ate for a fortnight, and during the other fortnight led the life of a pigeon, collecting a drona of corn.

And celebrating the Darsa and Paurnamasya sacrifices, that one devoid of guile, used to pass his days by taking the food that remained after the deities and the guests had eaten. And on auspicious lunar days, that lord of the three worlds, Indra himself, accompanied by the celestials used, O mighty monarch, to partake of the food offered at his sacrifice.

And that one, having adopted the life of a Muni, with a cheerful heart entertained his guests also with food on such days. And as that high-souled one distributed his food with alacrity, the remainder of the drona of corn increased as soon as a guest appeared. And by virtue of the pure spirit in which the sage gave a way, that food of his increased so much that hundreds upon hundreds of learned Brahmanas were fed with it.

("Vyasa continued, )

"And, O king, it came to pass that having heard of the virtuous Mudgala observant of vows, the Muni Durvasa, having space alone for his covering,[2] his accoutrements worn like that of maniac, and his head bare of hair, came there, uttering, O Pandava various insulting words.

And having arrived there that best of Munis said unto the Brahmana.

'Know you, O foremost of Brahmanas, that I have come hither seeking for food.'

Thereupon Mudgala said unto the sage,

'You are welcome!'

And then offering to that maniac of an ascetic affected by hunger, water to wash his feet and mouth, that one observant of the vow of feeding guests, respectfully placed before him excellent fare. Affected by hunger, the frantic Rishi completely exhausted the food that had been offered unto him.

Thereupon, Mudgala furnished him again with food. Then having eaten up all that food, he besmeared his body with the unclean orts and went away as he had come. In this manner, during the next season, he came again and ate up all the food supplied by that wise one leading the Uncha mode of life. Thereupon, without partaking any food himself, the sage Mudgala again became engaged in collecting corn, following the Uncha mode.

Hunger could not disturb his equanimity. Nor could anger, nor guile, nor a sense of degradation, nor agitation, enter into the heart of that best of Brahmanas leading the Uncha mode of life along with his son and his wife. In this way, Durvasa having made up his mind, during successive seasons presented himself for six several times before that best of sages living according to the Uncha mode; yet that Muni could not perceive any agitation in Mudgala’s heart; and he found the pure heart of the pure-souled ascetic always pure.

Thereupon, well-pleased, the sage addressed Mudgala, saying, 'There is not another guileless and charitable being like you on earth. The pangs of hunger drive away to a distance the sense of righteousness and deprive people of all patience. The tongue, loving delicacies, attracts men towards them.

Life is sustained by food. The mind, moreover, is fickle, and it is hard to keep it in subjection. The concentration of the mind and of the senses surely constitutes ascetic austerities. It must be hard to renounce in a pure spirit a thing earned by pains. Yet, O pious one, all this has been duly achieved by you. In your company we feel obliged and gratified. Self-restraint, fortitude, justice, control of the senses and of faculties, mercy, and virtue, all these are established in you.

You have by the deeds conquered the different worlds and have thereby obtained admission into paths of beautitude. Ah! even the dwellers of heaven are proclaiming your mighty deeds of charity. O you observant of vows, you shalt go to heaven even in thine own body.

("Vyasa continued, )

"Whilst the Muni Durvasa was speaking thus, a celestial messenger appeared before Mudgala, upon a car yoked with swans and cranes, hung with a neat work of bells, scented with divine fragrance, painted picturesquely, and possessed of the power of going everywhere at will.

And he addressed the Brahmana sage, saying,

'O sage, do you ascend into this chariot earned by your acts. You have attained the fruit of your asceticism!'

("Vyasa continued, )

"As the messenger of the gods was speaking thus, the sage told him,

'O divine messenger, I desire that you mayst describe unto me the attributes of those that reside there. What are their austerities, and what their purposes? And, O messenger of the gods, what constitutes happiness in heaven, and what are the disadvantages thereof? It is declared by virtuous men of good lineage that friendship with pious people is contracted by only walking with them seven paces.

O lord, in the name of that friendship I ask you,

'Do you without hesitation tell me the truth, and that which is good for me now. Having heard you, I shall, according to your words, ascertain the course I ought to follow.'"

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Picking up for support (1) ears of corn and (2) individual grains, left on the field by husbandmen after they have gathered and carried away the sheaves, are called the Sila and the Unchha modes of life.

[2]:

Naked.

Conclusion:

This concludes Section CCLVIII of Book 3 (Vana Parva) of the Mahabharata, of which an English translation is presented on this page. This book is famous as one of the Itihasa, similair in content to the eighteen Puranas. Book 3 is one of the eighteen books comprising roughly 100,000 Sanskrit metrical verses.

FAQ (frequently asked questions):

Which keywords occur in Section CCLVIII of Book 3 of the Mahabharata?

The most relevant definitions are: Mudgala, Muni, Brahmana, Uncha, Vyasa, Durvasa; since these occur the most in Book 3, Section CCLVIII. There are a total of 18 unique keywords found in this section mentioned 46 times.

What is the name of the Parva containing Section CCLVIII of Book 3?

Section CCLVIII is part of the Ghosha-yatra Parva which itself is a sub-section of Book 3 (Vana Parva). The Ghosha-yatra Parva contains a total of 27 sections while Book 3 contains a total of 13 such Parvas.

Can I buy a print edition of Section CCLVIII as contained in Book 3?

Yes! The print edition of the Mahabharata contains the English translation of Section CCLVIII of Book 3 and can be bought on the main page. The author is Kisari Mohan Ganguli and the latest edition (including Section CCLVIII) is from 2012.