Mahabharata (English)

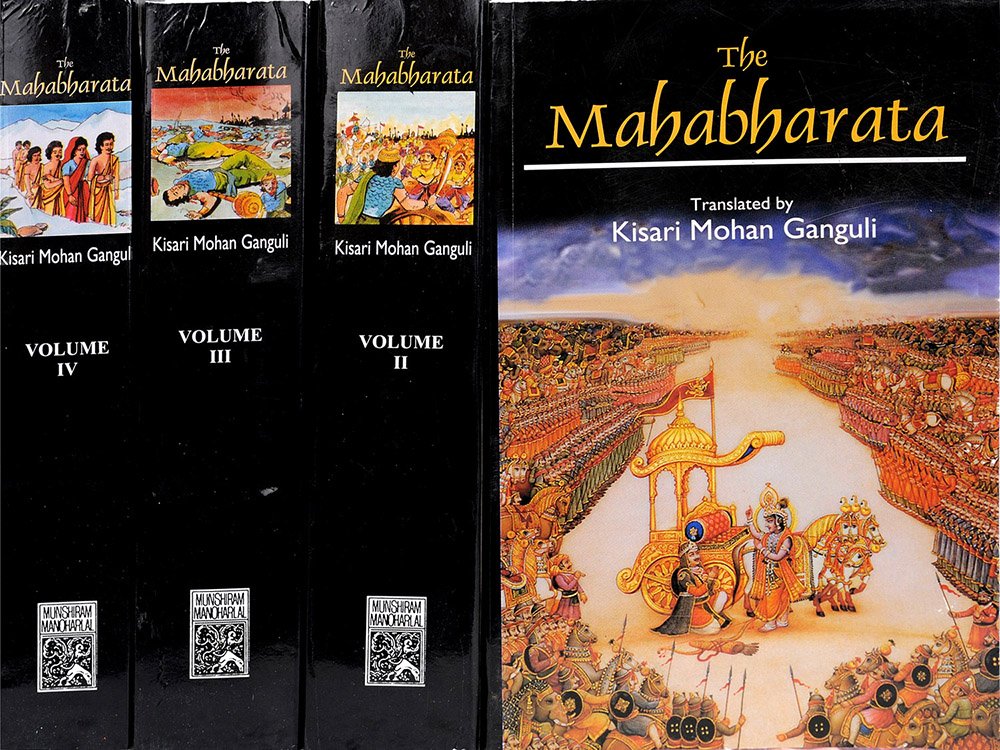

by Kisari Mohan Ganguli | 2,566,952 words | ISBN-10: 8121505933

The English translation of the Mahabharata is a large text describing ancient India. It is authored by Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa and contains the records of ancient humans. Also, it documents the fate of the Kauravas and the Pandavas family. Another part of the large contents, deal with many philosophical dialogues such as the goals of life. Book...

Section XC

"Vaisampayana said, 'Janardana, the chastiser of foes, after his meeting with Vidura, went then in the afternoon to his paternal aunt, Pritha. And beholding Krishna whose countenance beamed with the effulgence of the radiant sun arrived at her abode, she encircled his neck with her arms and began to pour forth her lamentations remembering her sons. And at the sight, after a long time, of Govinda of Vrishni’s race, the companion of those mighty children of hers, the tears of Pritha flowed fast.

And after Krishna, that foremost of warriors, had taken his seat having first received the rites of hospitality, Pritha, with a woe-begone face and voice choked with tears addressed him, saying:

'They, who, from their earliest years have always waited with reverence on their superiors; they, who, in friendship are attached to one another; they, who, deprived deceitfully of their kingdom had gone to seclusion, however worthy of living in the midst of friends and attendants,—they, who have subjugated both wrath and joy, are devoted to Brahman’s, and truthful in speech,—those children of mine, who, abandoning kingdom and enjoyments and leaving my miserable self behind, had gone to the woods, plucking the very roots of my heart,—those illustrious sons of Pandu, O Kesava, who have suffered woe however undeserving of it,—how, alas, did they live in the deep forest abounding with lions and tigers and elephants? Deprived in their infancy of their father, they were all tenderly brought up by me. How, also, did they live in the mighty forest, without seeing both their parents? From their infancy, O Kesava, the Pandavas were aroused from their beds by the music of conchs and drums and flutes.

That they who while at home, used to sleep in high palatial chambers on soft blankets and skins of the Runku deer and were waked up in the morning by the grunt of elephants, the neighing of steeds, the clatter of car-wheels and the music of conchs and cymbals in accompaniment with the notes of flutes and lyres,—who, adored at early dawn with sacred sounding hymns uttered by Brahmanas, worshipped those amongst them that deserved such worship with robes and jewels and ornaments, and who were blessed with the auspicious benedictions of those illustrious members of the regenerate order, as a return for the homage the latter received,—that they, O Janardana, could sleep in the deep woods resounding with the shrill and dissonant cries of beasts of prey can hardly be believed, undeserving as they were of so much woe.

How could they, O slayer of Madhu, who were roused from their beds by music of cymbals and drums and conchs and flutes, with the honeyed strains of songstresses and the eulogies chanted by bards and professional reciters,—alas, how could they be waked in the deep woods by the yells of wild beasts?

He that is endued with modesty, is firm in truth, with senses under control and compassions for all creatures,—he that has vanquished both lust and malice and always treads the path of the righteous, he that ably bore the heavy burthen borne by Amvarisha and Mandhatri Yayati and Nahusha and Bharata and Dilip and Sivi the son of Usinara and other royal sages of old, he that is endued with an excellent character and disposition, he that is conversant with virtue, and whose prowess is incapable of being baffled, he that is fit to become the monarch of the three worlds in consequence of his possession of every accomplishment, he that is the foremost of all the Kurus lawfully and in respect of learning and disposition, who is handsome and mighty-armed and has no enemy,—Oh, how is that Yudhishthira of virtuous soul, and of complexion like that of pure gold?

He that has the strength of ten thousand elephants and the speed of the wind, he that is mighty and ever wrathful amongst the sons of Pandu, he that always does good to his brothers and is, therefore, dear to them all, he, O slayer of Madhu, that slew Kicaka with all his relatives, he that is the slayer of the Krodhavasas, of Hidimva, and of Vaka, he that in prowess is equal unto Sakra, and in might unto the Wind-god, he that is terrible, and in wrath is equal unto Madhava himself, he that is the foremost of all smiters,—that wrathful son of Pandu and chastiser of foes, who, restraining his rage, might, impatience, and controlling his soul, is obedient to the commands of his elder brother,—speak to me, O Janardana, tell me how is that smiter of immeasurable valour, that Bhimasena, who in aspect also justifies his name—that Vrikodara possessing arms like maces, that mighty second son of Pandu?

O Krishna, that Arjuna of two arms who always regards himself as superior to his namesake of old with thousand arms, and who at one stretch shoots five hundred arrows, that son of Pandu who in the use of weapons is equal unto king Kartavirya, in energy unto Aditya, in restraint of senses unto a great sage, in forgiveness unto the Earth, and in prowess unto Indra himself,—he, by whose prowess, O slayer of Madhu, the Kurus amongst all the kings of the earth have obtained this extensive empire, blazing with effulgence,—he, whose strength of arms is always adored by the Pandavas,—that son of Pandu, who is the foremost of all car-warriors and whose prowess is incapable of being frustrated,—he, from an encounter with whom in battle no foe ever escapes with life,—he, O Achyuta, who is the conqueror of all, but who is incapable of being conquered by any,—he, who is the refuge of the Pandavas like Vasava of the celestials,—how, O Kesava, is that Dhananjaya now, that brother and friend of thine?

He that is compassionate to all creatures, is endued with modesty and acquainted with mighty weapons, is soft and delicate and virtuous,—he that is dear to me,—that mighty bowman Sahadeva, that hero and ornament of assemblies,—he, O Krishna, who is youthful in years, is devoted to the service of his brothers, and is conversant with both virtue and profit, whose brothers, O slayer of Madhu, always applaud the disposition of that high-souled and well-behaved son of mine,—tell me, O you of the Vrishni race, of that heroic Sahadeva, that foremost of warriors, that son of Madri, who always waites submissively on his elder brothers and so reverentially on me.

He that is delicate and youthful in years, he that is brave and handsome in person,—that son of Pandu who is dear unto his brothers as also unto all, and who, indeed, is their very life though walking with a separate body,—he that is conversant with various modes of warfare,—he that is endued with great strength and is a mighty bowman,—tell me, O Krishna, whether that dear child of mine, Nakula, who was brought up in luxury, is now well in body and mind? O you of mighty arms, shall I ever behold again Nakula of mine, that mighty car-warrior, that delicate youth brought up in every luxury and undeserving of woe? Behold, O hero, I am alive today, even I, who could know peace by losing sight of Nakula for the short space of time taken up by a wink of the eye.

More than all my sons, O Janardana, is the daughter of Drupada dear to me. High-born and possessed of great beauty, she is endued with every accomplishment. Truthful in speech, she chose the company of her lords, giving up that of her sons, Indeed, leaving her dear children behind, she follows the sons of Pandu. Waited upon at one time by a large train of servants, and adored by her husbands with every object of enjoyment, the possessor of every auspicious mark and accomplishment, how, O Achyuta, is that Draupadi now? Having five heroic husbands who are all smiters of foes and all mighty bowmen, each equal unto Agni in energy, alas, woe has yet been the lot of Drupada’s daughter. I have not for fourteen long years, O chastiser of foes, beheld the princess of Pancala, that daughter-in-law of mine who herself has been a prey to constant anxiety on account of her children, whom she has not seen for that period.

When Drupada’s daughter endued with such a disposition, does not enjoy uninterrupted happiness, it seems, O Govinda, that the happiness one enjoys is never the fruit of one’s acts. When I remember the forcible dragging of Draupadi to the assembly, then neither Vibhatsu nor Yudhishthira, nor Bhima, nor Nakula, nor Sahadeva, becomes an object of affection to me. Never before had a heavier grief been mine than what pierced my heart when that wretch Dussasana, moved by wrath and covetousness, dragged Draupadi, then in her flow, and therefore clad in a single raiment, into the presence of her father-in-law in the assembly and exposed her to the gaze of all the Kurus.

It is known that amongst those that were present, king Vahlika, Kripa, Somadatta, were pierced with grief at this sight, but of all present in that assembly, it was Vidura whom I worship. Neither by learning, nor by wealth does one become worthy of homage. It is by disposition alone that one becomes respectable, O Krishna, endued with great intelligence and profound wisdom, the character of the illustrious Vidura, like unto an ornament (that he wears) adorns the whole world.'

"Vaisampayana continued, 'Filled with delight at the advent of Govinda, and afflicted with sorrow (on account of her sons) Pritha gave expression to all her diverse griefs.

And she said,

'Can gambling and the slaughter of deer, which, O chastiser of foes, occupied all wicked kings of old, be a pleasant occupation for the Pandavas? The thought consumes, O Kesava, that being dragged into the presence of all the Kurus in their assembly by Dhritarashtra’s sons, insults worse than death were heaped on Krishna, O chastiser of foes, the banishment of my sons from their capital and their wanderings in the wilderness,—these and various other griefs, O Janardana, have been mine. Nothing could be more painful to me or to my sons themselves, O Madhava, than that they should have had to pass a period of concealment, shut up in a stranger’s house. Full fourteen years have passed since the day when Duryodhana first exited my sons. If misery is destructive of fruits of sins, and happiness is dependent on the fruits of religious merit, then it seems that happiness may still be ours after so much misery. I never made any distinction between Dhritarashtra’s sons and mine (so far as maternal affection is concerned). By that truth, O Krishna, I shall surely behold you along with the Pandavas safely come out of the present strife with their foes slain, and the kingdom recovered by them.

The Pandavas themselves have observed their vow with such truthfulness sticking to Dharma that they are incapable of being defeated by their enemies. In the matter of my present sorrows, however, I blame neither myself nor Suyodhana, but my father alone. Like a wealthy man giving away a sum of money in gift, my father gave me away to Kuntibhoja. While a child playing with a ball in my hands, your grandfather, O Kesava, gave me away to his friend, the illustrious Kuntibhoja. Abandoned, O chastiser of foes, by my own father, and my father-in law, and afflicted with insufferable woes, what use, O Madhava, is there in my being alive?

On the night of Savyasachin’s birth, in the lying-in-room, an invisible voice told me,

'This son of thine will conquer the whole world, and his fame will reach the very heavens. Slaying the Kurus in a great battle and recovering the kingdom, your son Dhanajaya will, with his brothers, perform three grand sacrifices.'

I do not doubt the truth of that announcement. I bow unto Dharma that upholds the creation. If Dharma be not a myth, then, O Krishna, you will surely achieve all that the invisible voice said. Neither the loss of my husband, O Madhava, nor loss of wealth, nor our hostility with the Kurus ever inflicted such rending pains on me as that separation from my children. What peace can my heart know when I do not see before me that wielder of Gandiva, viz., Dhananjaya, that foremost of all bearers of arms? I have not, for fourteen years, O Govinda, seen Yudhishthira, and Dhananjaya, and Vrikodara. Men perform the obsequies of those that are missed for a long time, taking them for dead. Practically, O Janardana, my children are all dead to me and I am dead to them.

'Say unto the virtuous king Yudhishthira, O Madhava, that-Your virtue, O son, is daily decreasing. Act you, therefore, in such a way that your religious merit may not diminish. Fie to them that live, O Janardana, by dependence on others. Even death is better than a livelihood gained by meanness. You must also say unto Dhananjaya and the ever-ready Vrikodara that—The time for that event is come in view of which a Kshatriya woman brings forth a son. If you allow the time slip without your achieving anything, then, though at present you are respected by all the world, you will be only doing that which would be regarded as contemptible. And if contempt touches you, I will abandon you for ever. When the time comes, even life, which is so dear, should be laid down, O foremost of men, you must also say unto Madri’s sons that are always devoted to Kshatriya customs.—More than life itself, strive you to win objects of enjoyment, procurable by prowess, since objects won by prowess alone can please the heart of a person desirous of living according to Kshatriya customs.

Repairing thither, O mighty-armed one, say unto that foremost of all bearers of arms, Arjuna the heroic son of Pandu,—Tread you the path that may be pointed out to you by Draupadi. It is known to you, O Kesava, that when inflamed with rage, Bhima and Arjuna, each like unto the universal Destroyer himself, can slay the very gods. That was a great insult offered unto them, viz., that their wife Krishna, having been dragged into the assembly was addressed in such humiliating terms by Dussasana and Karna. Duryodhana himself has insulted Bhima of mighty energy in the very presence of the Kuru chiefs. I am sure he will reap the fruit of that behaviour, for Vrikodara, provoked by a foe, knows no peace. Indeed, once provoked, Bhima forgets it not for a long while, even until that grinder of foes exterminates the enemy and his allies.

The loss of kingdom did not grieve me; the defeat at dice did not grieve me. That the illustrious and beautiful princess of Pancala was dragged into the assembly while clad in a single raiment and made to hear bitter words grieved me most. What, O Krishna, could be a greater grief to me? Alas, ever devoted to Kshatriya customs and endued with great beauty, the princess, while ill, underwent that cruel treatment, and though possessing powerful protectors was then as helpless as if she had none. O slayer of Madhu, having you and that foremost of all mighty persons, Rama, and that mighty car-warrior Pradyumna for me and my children’s protectors and having, O foremost of men, my sons the invincible Bhima and the unretreating Vijaya both alive, that I had still such grief to bear is certainly strange!'

"Vaisampayana continued, 'Thus addressed by her, Sauri the friend of Partha, then comforted his paternal aunt, Pritha, afflicted with grief on account of her sons.

And Vasudeva said,

'What woman is there, O aunt, in the world who is like you? The daughter of king Surasena, you are, by marriage, admitted into Ajamida’s race. High-born and highly married, you are like a lotus transplanted from one mighty lake into another. Endued with every prosperity and great good fortune, you were adored by your husband. The wife of hero, you have again given birth to heroic sons. Possessed of every virtue, and endued with great wisdom, it behoves you to bear with patience, both happiness and misery.

Overcoming sleep and langour, and wrath and joy, and hunger and thirst, and cold and heat, your children are always in the enjoyment of that happiness, which, as heroes, should by theirs. Endued with great exertion and great might, your sons, without affecting the comforts derivable from the senses such as satisfy only the low and the mean, always pursue that happiness which as heroes they should. Nor are they satisfied like little men having mean desires. They that are wise enjoy or suffer the same of whatever enjoyable or sufferable, Indeed, ordinary persons, affecting comforts that satisfy the low and the mean, desire an equable state of dullness, without excitement of any kind. They, however, that are superior, desire either the acutest of human suffering or the highest of all enjoyments that is given to man.

The wise always delight in extremes. They find no pleasure betwixt; they regard the extreme to be happiness, while that which lies between is regarded by them as misery. The Pandavas with Krishna salutes you through me. Representing themselves to be well, they have enquired after your welfare. You will soon behold them become the lords of the whole world, with their foe slain, and themselves invested with prosperity.'

'Thus consoled by Krishna, Kunti, afflicted with grief on account of her sons, but soon dispelling the darkness caused by her temporary loss of understanding, replied unto Janardana, saying,

'Whatever, O mighty-armed one, you, O slayer of Madhu, regardest as proper to be done, let that be done without sacrificing righteousness, O chastiser of foes, and without the least guile. I know, O Krishna, what the power of your truth and of your lineage is. I know also what judgment and what prowess you bringest to bear upon the accomplishment of whatever concerns your friends. In our race, you are Virtue’s self, you are Truth, and you are the embodiment of ascetic austerities. You are the great Brahma, and everything rests on you. What, therefore, you have said must be true.'

"Vaisampayana continued, 'Bidding her farewell and respectfully walking round her, the mighty-armed Govinda then departed for Duryodhana’s mansion.'"

Conclusion:

This concludes Section XC of Book 5 (Udyoga Parva) of the Mahabharata, of which an English translation is presented on this page. This book is famous as one of the Itihasa, similair in content to the eighteen Puranas. Book 5 is one of the eighteen books comprising roughly 100,000 Sanskrit metrical verses.

FAQ (frequently asked questions):

Which keywords occur in Section XC of Book 5 of the Mahabharata?

The most relevant definitions are: Krishna, Pandu, Janardana, Pandavas, Kuru, Kesava; since these occur the most in Book 5, Section XC. There are a total of 68 unique keywords found in this section mentioned 181 times.

What is the name of the Parva containing Section XC of Book 5?

Section XC is part of the Bhagavat-Yana Parva which itself is a sub-section of Book 5 (Udyoga Parva). The Bhagavat-Yana Parva contains a total of 89 sections while Book 5 contains a total of 4 such Parvas.

Can I buy a print edition of Section XC as contained in Book 5?

Yes! The print edition of the Mahabharata contains the English translation of Section XC of Book 5 and can be bought on the main page. The author is Kisari Mohan Ganguli and the latest edition (including Section XC) is from 2012.