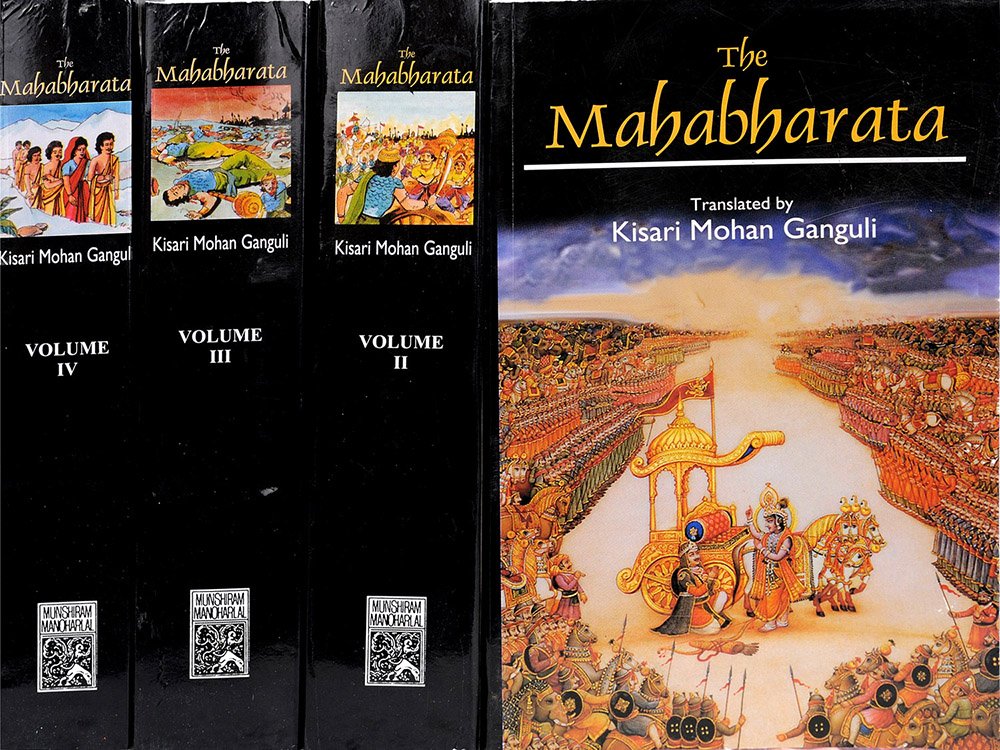

Mahabharata (English)

by Kisari Mohan Ganguli | 2,566,952 words | ISBN-10: 8121505933

The English translation of the Mahabharata is a large text describing ancient India. It is authored by Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa and contains the records of ancient humans. Also, it documents the fate of the Kauravas and the Pandavas family. Another part of the large contents, deal with many philosophical dialogues such as the goals of life. Book...

Section IV

Yudhishthira said,

"You have already said what offices you will respectively perform. I also, according to the measure of my sense, have said what office I will perform. Let our priest, accompanied by charioteers and cooks, repair to the abode of Drupada, and there maintain our Agnihotra fires. And let Indrasena and the others, taking with then the empty cars, speedily proceeded to Dwaravati. Even this is my wish. And let all these maid-servants of Draupadi go to the Pancalas, with our charioteers and cooks. And let all of them say,—We do not know where the Pandavas have gone leaving us at the lake of Dvaitavana."

Vaisampayana said, "Having thus taken counsel of one another and told one another the offices they would discharge, the Pandavas sought Dhaumya’s advice. And Dhaumya also gave them advice in the following words, saying,

You sons of Pandu, the arrangements you have made regarding the Brahmanas, yours friends, cars, weapons, and the (sacred) fires, are excellent. But it behoves you, O Yudhishthira, and Arjuna specially, to make provision for the protection of Draupadi. You king, you are well-acquainted with the characters of men. Yet whatever may be your knowledge, friends may from affection be permitted to repeat what is already known. Even this is subservient to the eternal interests of virtue, pleasure, and profit. I shall, therefore speak to you something. Mark you. To dwell with a king is, alas, difficult. I shall tell you, you princes, how you may reside in the royal household, avoiding every fault. You Kauravas, honourably or otherwise, you will have to pass this year in the king’s palace, undiscovered by those that know you. Then in the fourteenth year, you will live happy. O son of Pandu, in this world, that cherisher and protector of all beings, the king, who is a deity in an embodied form, is as a great fire sanctified with all the mantras.[1]

One should present himself before the king, after having obtained his permission at the gate. No one should keep contact with royal secrets. Nor should one desire a seat which another may covet. He who does not, regarding himself to be a favourite, occupy (the king’s) car, or coach, or seat, or vehicle, or elephant, is alone worthy of dwelling in a royal household. He that sits not upon a seat the occupation of which is calculated raise alarm in the minds of malicious people, is alone worthy of dwelling in a royal household. No one should, unasked offer counsel (to a king). Paying homage in season unto the king, one should silently and respectfully sit beside the king, for kings take umbrage at babblers, and disgrace laying counsellors. A wise person should not contact friendship with the king’s wife, nor with the inmates of the inner apartments, nor with those that are objects of royal displeasure. One about the king should do even the most unimportant acts and with the king’s knowledge. Behaving thus with a sovereign, one does not come by harm. Even if an individual attain the highest office, he should, as long as he is not asked or commanded, consider himself as born-blind, having regard to the king’s dignity, for O repressers of foes, the rulers of men do not forgive even their sons and grandsons and brothers when they happen to tamper with their dignity. Kings should be served with regardful care, even as Agni and other god; and he that is disloyal to his sovereign, is certainly destroyed by him. Renouncing anger, and pride, and negligence, it behoves a man to follow the course directed by the monarch. After carefully deliberating on all things, a person should set forth before the king those topics that are both profitable and pleasant; but should a subject be profitable without being pleasant, he should still communicate it, despite its disagreeableness. It behoves a man to be well-disposed towards the king in all his interests, and not to indulge in speech that is alike unpleasant and profitless. Always thinking—I am not liked by the king—one should banish negligence, and be intent on bringing about what is agreeable and advantageous to him. He that swerves not from his place, he that is not friendly to those that are hostile to the king, he that strives not to do wrong to the king, is alone worthy to dwell in a royal household. A learned man should sit either on the king’s right or the left; he should not sit behind him for that is the place appointed for armed guards, and to sit before him is always interdicted. Let none, when the king is engaged in doing anything (in respect of his servants) come forward pressing himself zealously before others, for even if the aggrieved be very poor, such conduct would still be inexcusable.[2]

It behoves no man to reveal to others any lie the king may have told inasmuch as the king bears ill will to those that report his falsehoods. Kings also always disregard persons that regard themselves as learned. No man should be proud thinking—I am brave, or, I am intelligent, but a person obtains the good graces of a king and enjoys the good things of life, by behaving agreeably to the wishes of the king. And, O Bharata, obtaining things agreeable, and wealth also which is so hard to acquire, a person should always do what is profitable as well as pleasant to the king. What man that is respected by the wise can even think of doing mischief to one whose ire is great impediment and whose favour is productive of mighty fruits? No one should move his lips, arms and thighs, before the king. A person should speak and spit before the king only mildly. In the presence of even laughable objects, a man should not break out into loud laughter, like a maniac; nor should one show (unreasonable) gravity by containing himself, to the utmost. One should smile modestly, to show his interest (in what is before him). He that is ever mindful of the king’s welfare, and is neither exhilarated by reward nor depressed by disgrace, is alone worthy of dwelling in a royal household. That learned courtier who always pleases the king and his son with agreeable speeches, succeeds in dwelling in a royal household as a favourite. The favourite courtier who, having lost the royal favour for just reason, does not speak evil of the king, regains prosperity. The man who serves the king or lives in his domains, if sagacious, should speak in praise of the king, both in his presence and absence. The courtier who attempts to obtain his end by employing force on the king, cannot keep his place long and incurs also the risk of death. None should, for the purpose of self-interest, open communications with the king’s enemies.[3]

Nor should one distinguish himself above the king in matters requiring ability and talents. He that is always cheerful and strong, brave and truthful, and mild, and of subdued senses, and who follows his master like his shadow, is alone worthy to dwell in a royal household. He that on being entrusted with a work, comes forward, saying,—I will do this—is alone worthy of living in a royal household. He that on being entrusted with a task, either within the king’s dominion or out of it, never fears to undertake it, is alone fit to reside in a royal household. He that living away from his home, does no remember his dear ones, and who undergoes (present) misery in expectation of (future) happiness, is alone worthy of dwelling in a royal household. One should not dress like the king, nor should one indulge, in laughter in the king’s presence nor should one disclose royal secrets. By acting thus one may win royal favour. Commissioned to a task, one should not touch bribes for by such appropriation one becomes liable to fetters or death. The robes, ornaments, cars, and other things which the king may be pleased to bestow should always be used, for by this, one wins the royal favour. You children, controlling your minds, do you spend this year, you sons of Pandu, behaving in this way. Regaining your own kingdom, you may live as you please."

Yudhishthira said,

"We have been well taught by you. Blessed be you. There is none that could say so to us, save our mother Kunti and Vidura of great wisdom. It behoves you to do all that is necessary now for our departure, and for enabling us to come safely through this woe, as well as for our victory over the foe."

Vaisampayana continued, "Thus addressed by Yudhishthira, Dhaumya, that best of Brahmanas, performed according to the ordinance the rites ordained in respect of departure. And lighting up their fires, he offered, with mantras, oblations on them for the prosperity and success of the Pandavas, as for their reconquest of the whole world. And walking round those fires and round the Brahmanas of ascetic wealth, the six set out, placing Yajnaseni in their front. And when those heroes had departed, Dhaumya, that best of ascetics, taking their sacred fires, set out for the Pancalas. And Indrasena, and others already mentioned, went to the Yadavas, and looking after the horses and the cars of the Pandavas passed their time happily and in privacy."

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Some of the Bengal text and Sarvastramaya for Sarvamantramaya. The former is evidently incorrect.

[2]:

This is a very difficult sloka. Nilakantha adopts the reading Sanjayet. The Bengal editions read Sanjapet. If the latter be the correct reading, the meaning then would be,--'Let none talk about what transpires in the presence of the king. For those even that are poor, regard it as a grave fault.' The sense evidently is that the occurrences in respect of a king which one witnesses should not be divulged. Even they that are powerless regard such divulgence of what occurs in respect of them as an insult to them, and, therefore, inexcusable.

Conclusion:

This concludes Section IV of Book 4 (Virata Parva) of the Mahabharata, of which an English translation is presented on this page. This book is famous as one of the Itihasa, similair in content to the eighteen Puranas. Book 4 is one of the eighteen books comprising roughly 100,000 Sanskrit metrical verses.

FAQ (frequently asked questions):

Which keywords occur in Section IV of Book 4 of the Mahabharata?

The most relevant definitions are: Yudhishthira, Pandavas, Dhaumya, Pandu, Brahmanas, Pancalas; since these occur the most in Book 4, Section IV. There are a total of 20 unique keywords found in this section mentioned 38 times.

What is the name of the Parva containing Section IV of Book 4?

Section IV is part of the Pandava-Pravesa Parva which itself is a sub-section of Book 4 (Virata Parva). The Pandava-Pravesa Parva contains a total of 12 sections while Book 4 contains a total of 4 such Parvas.

Can I buy a print edition of Section IV as contained in Book 4?

Yes! The print edition of the Mahabharata contains the English translation of Section IV of Book 4 and can be bought on the main page. The author is Kisari Mohan Ganguli and the latest edition (including Section IV) is from 2012.