Satapatha-brahmana

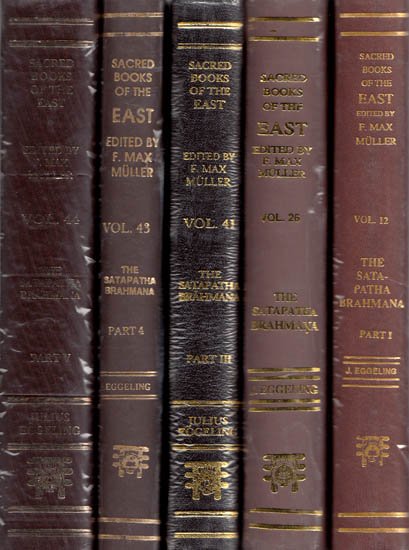

by Julius Eggeling | 1882 | 730,838 words | ISBN-13: 9788120801134

This is Satapatha Brahmana X.4.2 English translation of the Sanskrit text, including a glossary of technical terms. This book defines instructions on Vedic rituals and explains the legends behind them. The four Vedas are the highest authortity of the Hindu lifestyle revolving around four castes (viz., Brahmana, Ksatriya, Vaishya and Shudra). Satapatha (also, Śatapatha, shatapatha) translates to “hundred paths”. This page contains the text of the 2nd brahmana of kanda X, adhyaya 4.

Kanda X, adhyaya 4, brahmana 2

[Sanskrit text for this chapter is available]

1. Verily, Prajāpati, the year, is Agni, and King Soma, the moon. He himself, indeed, proclaimed (taught) his own self to Yajñavacas Rājastambāyana, saying, 'As many lights as there are of mine, so many are my bricks.'

2. Now in this Prajāpati, the year, there are seven hundred and twenty days and nights, his lights, (being) those bricks; three hundred and sixty enclosing-stones[1], and three hundred and sixty bricks with (special) formulas. This Prajāpati, the year, has created all existing things, both what breathes and the breathless, both gods and men. Having created all existing things, he felt like one emptied out, and was afraid of death.

3. He bethought himself, 'How can I get these beings back into my body? how can I put them back into my body? how can I be again the body of all these beings?'

4. He divided his body into two; there were three hundred and sixty bricks in the one, and as many in the other: he did trot succeed[2].

5. He made himself three bodies,--in each of them there were three eighties of bricks I he did not succeed.

6. He made himself four bodies of a hundred and eighty bricks each: he did not succeed.

7. He made himself five bodies,--in each of them there were a hundred and forty-four bricks: he did not succeed.

8. He made himself six bodies of a hundred and twenty bricks each: he did not succeed. He did not develop himself sevenfold[3].

9. He made himself eight bodies of ninety bricks each: he did not succeed.

10. He made himself nine bodies of eighty bricks each: he did not succeed.

11. He made himself ten bodies of seventy-two bricks each: he did not succeed. He did not develop elevenfold.

12. He made himself twelve bodies of sixty bricks each: he did not succeed. He did not develop either thirteenfold or fourteenfold.

13. He made himself fifteen bodies of forty-eight bricks each: he did not succeed.

14. He made himself sixteen bodies of forty-five bricks each: he did not succeed. He did not develop seventeenfold.

15. He made himself eighteen bodies of forty bricks each: he did not succeed. He did not develop nineteenfold.

16. He made himself twenty bodies of thirty-six bricks each: he did not succeed. He did not develop either twenty-one-fold, or twenty-two-fold, or twenty-three-fold.

17. He made himself twenty-four bodies of thirty bricks each. There he stopped, at the fifteenth; and because he stopped at the fifteenth arrangement[4] there are fifteen forms of the waxing, and fifteen of the waning (moon).

18. And because he made himself twenty-four bodies, therefore the year consists of twenty-four half-months. With these twenty-four bodies of thirty bricks each he had not developed (sufficiently). He saw the fifteen parts of the day, the muhūrtas[5], as forms for his body, as space-fillers (Lokampṛṇās[6]), as well as fifteen of the night; and inasmuch as they straightway (muhu) save (trai), they are (called) 'muhūrtāḥ'; and inasmuch as, whilst being small, they fill (pūr) these worlds (or spaces, 'loka') they are (called) 'lokampṛṇāḥ.'

19. That one (the sun) bakes everything here, by means of the days and nights, the half-moons, the months, the seasons, and the year; and this (Agni, the fire) bakes what is baked by that one: 'A baker of the baked (he is),' said Bhāradvāja of Agni; 'for he bakes what has been baked by that (sun).'

20. In the year these (muhūrtas) amounted to ten thousand and eight hundred: he stopped at the ten thousand and eight hundred.

21. He then looked round over all existing things, and beheld all existing things in the threefold lore (the Veda), for therein is the body of all metres, of all stomas, of all vital airs, and of all the gods: this, indeed, exists, for it is immortal, and what is immortal exists; and this (contains also) that which is mortal.

22. Prajāpati bethought himself, 'Truly, all existing things are in the threefold lore: well, then, I will construct for myself a body so as to contain the whole threefold lore.'

23. He arranged the Ṛk-verses into twelve thousand of Bṛhatīs[7], for of that extent are the verses created by Prajāpati. At-the thirtieth arrangement they came to an end in the Paṅktis; and because it was at the thirtieth arrangement that they came to an end, there are thirty nights in the month; and because it was in the Paṅktis, therefore Prajāpati is 'pāṅkta' (fivefold)[8]. There are one hundred-and-eight hundred 2 Paṅktis.

24. He then arranged the two other Vedas into twelve thousand Bṛhatīs,--eight (thousand) of the Yajus (formulas), and four of the Sāman (hymns)--for of that extent is what was created by Prajāpati in these two Vedas. At the thirtieth arrangement these two came to an end in the Paṅktis; and because it was at the thirtieth arrangement that they came to an end, there are thirty nights in the month; and because it was in the Paṅktis, therefore Prajāpati is 'pāṅkta.' There were one hundred-and-eight hundred[9] Paṅktis.

25. All the three Vedas amounted to ten thousand eight hundred eighties (of syllables)[10]; muhūrta by muhūrta he gained a fourscore (of syllables), and muhūrta by muhūrta a fourscore was completed[11].

26. Into these three worlds, (in the form of) the fire-pan[12], he (Prajāpati) poured, as seed into the womb, his own self made up of the metres, stomas, vital airs, and deities. In the course of a half-moon the first body was made up, in a further (half-moon) the next (body), in a further one the next,--in a year he is made up whole and complete.

27. Whenever he laid down an enclosing-stone[13], he laid down a night, and along with that fifteen muhūrtas, and along with the muhūrtas fifteen eighties (of syllables of the sacred texts)[14]. And whenever he laid down a brick with a formula (yajushmatī), he laid down a day[15], and along with that fifteen muhūrtas, and along with the muhūrtas fifteen eighties (of syllables). In this manner he put this threefold lore into his own self, and made it his own; and in this very (performance) he became the body of all existing things, (a body) composed of the metres, stomas, vital airs, and deities; and having become composed of all that, he ascended upwards; and he who thus ascended is that moon yonder.

28. He who shines yonder (the sun) is his foundation, (for) over him he was built up[16], on him he was built up: from out of his own self he thus fashioned him, from out of his own self he generated him.

29. Now when he (the Sacrificer), being about to build an altar, undergoes the initiation-rite,--even as Prajāpati poured his own self, as seed, into the fire-pan as the womb,--so does he pour into the fire-pan, as seed into the womb, his own self composed of the metres, stomas, vital airs, and deities. In the course of a half-moon, his first body is made up, in a further (half-moon) the next (body), in a further one the next,--in a year he is made up whole and complete.

30. And whenever he lays down an enclosing-stone, he lays down a night, and along with that fifteen muhūrtas, and along with the muhūrtas fifteen eighties (of syllables). And whenever he lays down a Yajushmatī (brick), he lays down a day, and along with that fifteen muhūrtas, and along with the muhūrtas fifteen eighties (of syllables of the sacred texts). In this manner he puts this threefold lore into his own self, and makes it his own; and in this very (performance) he becomes the body of all existing things, (a body) composed of the metres, stomas, vital airs, and deities; and having become composed of all that, he ascends upwards.

31. And he who shines yonder is his foundation, for over him he is built up, on him he is built up: from out of his own self he thus fashions him, from out of his own self he generates him. And when he who knows this departs from this world, then he passes into that body composed of the metres, stomas, vital airs, and deities; and verily having become composed of all that, he who, knowing this performs this sacrificial work, or he who even knows it, ascends upwards.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

See X, 4, 2, 27 with note.

[2]:

Na vyāpnot, intrans., 'he did not attain (his object),' cf. vyāpti, in the sense of 'success';--(svayaṃ teṣām ātmā bhavitum) asamartho'bhavat. Sāyaṇa.

[3]:

Or, did not divide sevenfold, na saptadhā vyabhavat,--saptadhāvibhāgaṃ na kṛtavān. Sāyaṇa.

[4]:

Literally, shifting (about of the bricks of the altar), development.

[5]:

The day and night consists of thirty muhūrtas, a muhūrta being thus equal to about forty-eight minutes or four-fifths of an hour.

[6]:

The Lokampṛṇā bricks contained in the whole fire-altar amount to as many as there are muhūrtas in the year, viz. 10,800; see X, 4, 3, 20.

[7]:

The Bṛhatī verse, consisting of 36 syllables, this calculation makes the hymns of the Ṛg-veda to consist of 36 × 12,000= 432,000 syllables.

[8]:

The Paṅkti consists of five pādas (feet) of eight syllables each.

[9]:

That is to say, 10,800 Paṅktis, which, as the Paṅkti verse has 40 syllables, again amount to 432,000 syllables.

[10]:

The three Vedas, according to the calculations in paragraphs 23 and 24, contain 2 × 432,000 = 864,000 syllables, which is equal to 80 × 10,800. On the predilection to calculate by four-scores, see p. 112, note 1.

[11]:

That is, within the year, for the year has 360 × 30 = 10,800 muhūrtas, which is just the amount of eighties of which the three Vedas were said to consist. I do not see how any division of the 'muhūrta' itself into eighty parts (as supposed by Professor Weber, Ind. Streifen, I, p. 92, note 1) can be implied here.

[12]:

On the construction of the Ukhā, as representing the universe, see VI, 5, 2 seq.

[13]:

The number of 'pariśrits' by which the great altar is enclosed is only 261; but to these are usually added those of the other brick-built hearths, viz. the Gārhapatya (21) and the eight Dhiṣṇyas (78),--the whole amounting to 360 enclosing-stones, or one for each day (or night) in the year.

[14]:

According to paragraph 25, a fourscore of syllables was completed in each muhūrta; and day and night consist of fifteen muhūrtas each.

[15]:

See IX, 4, 3, 6, where the number of Yajushmatī bricks is said to be equal to that of the pariśrits, or enclosing-stones--with, however, 35 (36) added for the intercalary month, hence altogether 395 (396); cf. X, 4, 3, 14-19.

[16]:

Viz. inasmuch as the round gold plate, representing the sun, was laid down in the centre of the altar-site, before the first layer was built. Sāyaṇa.