Satapatha-brahmana

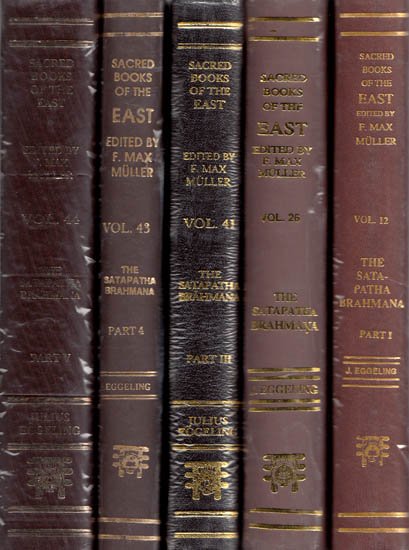

by Julius Eggeling | 1882 | 730,838 words | ISBN-13: 9788120801134

This is Satapatha Brahmana VIII.7.2 English translation of the Sanskrit text, including a glossary of technical terms. This book defines instructions on Vedic rituals and explains the legends behind them. The four Vedas are the highest authortity of the Hindu lifestyle revolving around four castes (viz., Brahmana, Ksatriya, Vaishya and Shudra). Satapatha (also, Śatapatha, shatapatha) translates to “hundred paths”. This page contains the text of the 2nd brahmana of kanda VIII, adhyaya 7.

Kanda VIII, adhyaya 7, brahmana 2

[Sanskrit text for this chapter is available]

1. He then lays down a Lokampṛṇā[1] (space-filling brick); the Lokampṛṇā, doubtless, is yonder sun, for he fills these worlds: it is thus yonder sun he thereby sets up. He lays down this (Lokampṛṇā) in all the (five) layers, for those layers are these (three) worlds[2]: he thus places the sun in (all) these worlds, whence he shines for all these worlds.

2. And, again, as to why he lays down a Lokampṛṇā,--the Lokampṛṇā, doubtless, is the nobility (or chieftaincy)[3], and these other bricks are the peasants (or clansmen): he thus places the nobility (or chieftain), as the eater, among the peasantry. He lays it down in all the layers: he thus places the nobility, as the eater, among the whole peasantry (or in every clan).

3. Now this is only a single (brick): he thus makes the nobility (or the chieftaincy) and (social) distinction to attach to a single (person). And what second (such brick there is) that is its mate,--a mate, doubtless, is one half of one's own self, for when one is with a mate then he is whole and complete: (thus it is laid down) for the sake of completeness. With a single formula he lays down many bricks[4]: he thereby endows the nobility preeminently with power[5], and makes the nobility more powerful than the peasantry. And the other (bricks) he lays down singly, with separate formulas: he thereby makes the peasantry less powerful than the nobility, differing in speech, and of different thoughts (from one another).

4. The first two (Lokampṛṇās) he lays down in that (south-east) corner: he thereby places yonder sun in that quarter: from this (earth) he follows him (the sun) from that (place) there[6]; from this (earth) he follows him from that (place) there; from this (earth) he follows hire from that (place) there; from this (earth) he follows him from that (place) there.

5. And in whatever place he lays down the first two (bricks), let him there lay down alongside of them the last two (bricks): for (otherwise) having once revolved round these worlds, that sun would not pass by them. Let him lay down the two last alongside the two first by reaching over them: he thus causes that sun to pass by these worlds; and hence that sun revolves incessantly round these worlds again and again (from left) to right.

6. [He lays them down, with, Vāj. S. XV, 59], 'Fill the space! fill the gap!'--that is, 'fill up the space! fill up the gap;'--'and lie thou steady!'--that is, 'and lie thou firm, settled!'--'Indra and Agni, and Bṛhaspati, have settled thee in this womb;' that is, 'Indra and Agni, and Bṛhaspati, have established thee in this womb.' Thus (he establishes them) by an anuṣṭubh verse; for the Anuṣṭubh is speech, and Indra is speech, and the space-filler is Indra. He does not settle them, for that (sun) is unsettled. He pronounces the Sūdadohas on them, for the Sūdadohas is vital air: he thus makes him (Agni) continuous and joins him together by means of the vital air.

7. Here now they say, 'How does that Lokampṛṇā become of unimpaired strength?' Well, the Lokampṛṇā is yonder sun, and he assuredly is of unimpaired strength. And the Lokampṛṇā also is speech, and of unimpaired strength assuredly is speech.

8. Having laid down those (bricks) possessed of (special) sacrificial formulas, he covers (the altar) with the Lokampṛṇā; for the bricks possessed of formulas mean food, and the Lokampṛṇā means the body: he thus encloses the food in the body, whence food enclosed in the body is the body itself.

9. Those (bricks) possessed of formulas he places on the body (of the altar) itself, not on the wings and tail: he thus puts food into the body; and whatever food is put into the body that benefits both the body and the wings and tail; but that which he puts on the wings and tail benefits neither the body, nor the wings and tail.

10. On the body (of the altar) he places both (bricks) possessed of formulas and Lokampṛṇās; whence that body (of a bird) is, as it were, twice as thick. On the wings and tail (he places) only Lokampṛṇās, whence the wings and tail are, as it were, thinner. On the body (of the altar) he places them both lengthwise and crosswise, for the bricks are bones: hence these bones in the body run both lengthwise and crosswise. On the wings and tail (he places them so as to be) turned away (from the body), for in the wings and tail there is not a single transverse bone. And this, indeed, is the difference between a built and an unbuilt (altar): suchlike is the built one, different therefrom the unbuilt one[7].

11. The Svayamātṛṇṇā (naturally-perforated brick) he encloses with Lokampṛṇā (bricks); for the naturally-perforated one is the breath, and the 'space-filler' is the sun: he thus kindles the breath by means of the sun, whence this breath (of ours) is warm. With that (kind of brick) he fills up the whole body: he thereby kindles the whole body by means of the sun, whence this whole body (of ours) is warm. And this, indeed, is the difference between one that will live and one that will die:

he that will live is warm, and he that will die is cold.

12. From the corner in which he lays down the first two (Lokampṛṇās) he goes on filling up (the altar) by tens up to the Svayamātṛṇṇā. In the same way he goes on filling it up from left to right behind the naturally-perforated one up to (the brick on) the cross-spine[8]. He then fills it up whilst returning to that limit[9].

13. The body (of the altar) he fills up first, for of (a bird) that is produced, the body is produced first, then the right wing, then the tail, then the left (wing): that is in the rightward (sunwise) way, for this is (the way) with the gods, and thus, indeed, yonder sun moves along these worlds from left to right.

14. The Lokampṛṇā, doubtless, is the same as the vital air; he therewith fills up the whole body (of the altar): he thus puts vital air into the whole body. If he were not to reach any member thereof, then the vital air would not reach that member of him (Agni); and whatever member the vital air does not reach, that, assuredly, either dries up or withers away: let him therefore fill up therewith the whole of it.

15. The wings and tail he builds on to the body, for the wings and tail grow on to the body; but were he first to lay down those (bricks) turned away (from the body), it would be as if he were to take a limb from elsewhere and put it on again.

16. Let him not lay down either a broken (brick) or a black one; for one that is broken causes failure, and sickly is that form which is black: 'Lest I should make up a sickly body,' he thinks[10]. Let him not throw aside an unbroken (brick), lest he should put what is not sickly outside the body. Whatever (bricks), in counting from the dhiṣṇya hearths, should exceed a Virāj[11], and not make up another, such (bricks) indeed cause failure: let him break them and throw them[12] (ut-kir) on the heap of rubbish (utkara), for the heap of rubbish is the seat of what is redundant: thus he thereby settles them where there is. the seat of that which is redundant.

17. Now, then, of the measures of the bricks. In the first and last layers let him lay down (bricks) of a foot (square), for the foot is a support; and the hand is the same as the foot. The largest (bricks) should be of the measure of the thigh-bone, for there is no bone larger than the thigh-bone. Three layers should have (their bricks) marked with three lines, for threefold are these worlds; and two (layers may consist) of (bricks) marked with an indefinite number of lines, for these two layers are the flavour, and the flavour is indefinite; but all (the layers) should rather have (bricks) marked with three lines, for threefold are all these worlds.

18. Now, then, of the location[13] of (special) bricks. Any (special) brick he knows, provided with a formula, let him place in the middle (third) layer; for the middle layer is the air, and the air, doubtless, is the location of all beings. Moreover, bricks with (special) formulas are food, and the middle layer is the belly: he thus puts food into the belly.

19. Here, now, they say, 'Let him not lay down (such special bricks) lest he should do what is excessive.' But he may, nevertheless, lay them down; for such bricks are laid down for (the fulfilment of special) wishes, and in wishes there is nothing excessive. But let him rather not lay them down, for just that much the gods then did.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

In laying down the Lokampṛṇās of the fifth layer, he begins, as in the first layer, from the right shoulder, or the south-east corner, of the altar, but so that in this case the first 'space-filler' is laid down, not at the corner, but a cubit to the west of it. Starting from that spot, he fills up the available spaces, in two turns, moving in the sunwise fashion.

[2]:

Rather, the first, second, and third layers are the three worlds.

[3]:

At VI, 1, 2, 25 Tāṇḍya was made to maintain that the Yajushmatīs, or bricks laid down with special formulas, were the nobility, and that the Lokampṛṇās, laid down with one and the same formula, were the peasants, and as the noble (or chieftain) required a numerous clan for his subsistence, there should be fewer of the former kind of bricks, than the established practice was. This view was however rejected by the author of the Brāhmaṇa, and here, in opposition to that view, the Lokampṛṇā is identified with the nobility, and the Yajushmatīs with the clan.

[4]:

The common formula used with these bricks, and from which they derive their name--beginning as it does 'Lokam pṛṇa,' 'Fill the space!' see parag. 6--is pronounced once only after every ten such bricks, and after any odd ones at the end.

[5]:

In the translation of VII, 5, 2, 14 (part iii, p. 404), the passage 'having taken possession of the man by strength,' which was based on a wrong reading (see Weber, Berl. Cat. II, p. 69), should read thus: 'having pre-eminently endowed man with power' (or, perhaps, 'having placed him above (others) in respect of power,' St. Petersb. Dict.)

[6]:

I do not know whether 'atas' might be taken here in the sense of 'thither,' or whether it goes along with 'tasmāt,' merely strengthening it. The meaning in either case would seem to be this. In the first turn of filling up the empty spaces he first moves along from the south-east corner (the point where the sun rises) to the back or west end of the spine (the place where the sun sets) and the central brick; and having thus, as it were, touched the earth again, he proceeds from there in the same sunwise fashion, filling up the north part of the altar until he reaches the east end of the spine, and there, as it were, touches the earth once more. In the second turn he again begins (with the second brick) in the south-east, and repeats the same process, in filling up the south part of the altar, and completing at the southeast corner. The laying down of the Lokampṛṇās would thus be supposed to occupy the full space of two days and two nights.

[7]:

That is, one not properly built.

[8]:

This would seem to be the Vikarṇī (see VIII, 7, 3, 9 seqq.) which, however, like the central Svayamātṛṇṇā, is only to be laid down after the layer has been levelled up.

[9]:

Viz. to the east end of the 'spine.'

[10]:

Here, as so often before, the effect to be avoided is expressed by a clause in oratio directa with 'ned'; the inserted clause with 'vai' indicating the reason why that effect is to be dreaded. To adapt the passage to our own mode of diction, we should have to translate:--Let him not lay down either a broken brick or a black one, lest he should form a sickly body; for a brick which is broken comes to grief, and what is black is of sickly appearance.--In the next sentence of the translation, the direct form of speech has been discarded.

[11]:

The pāda of the Virāj consists of ten, and a whole Virāj stanza of thirty (or forty), syllables. Hence the number of the bricks is to be divisible by ten.

[12]:

Or, perhaps, dig them in.

[13]:

Āvapana has also the meaning of 'throwing in, insertion,' which is likewise understood here, whilst further on in this paragraph ('the air is the āvapanam of all beings') it can scarcely have this meaning (? something injected). Cf. IX, 4, 2, 27.