Satapatha-brahmana

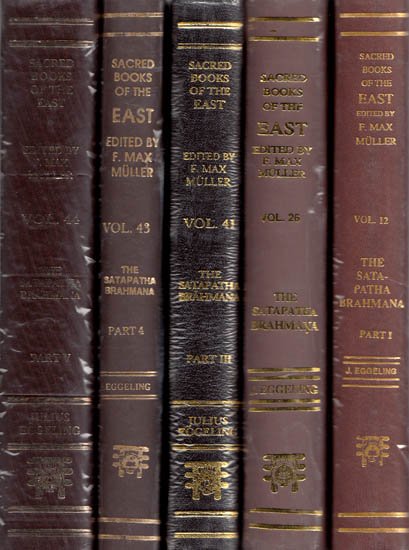

by Julius Eggeling | 1882 | 730,838 words | ISBN-13: 9788120801134

This is Satapatha Brahmana VIII.3.2 English translation of the Sanskrit text, including a glossary of technical terms. This book defines instructions on Vedic rituals and explains the legends behind them. The four Vedas are the highest authortity of the Hindu lifestyle revolving around four castes (viz., Brahmana, Ksatriya, Vaishya and Shudra). Satapatha (also, Śatapatha, shatapatha) translates to “hundred paths”. This page contains the text of the 2nd brahmana of kanda VIII, adhyaya 3.

Kanda VIII, adhyaya 3, brahmana 2

[Sanskrit text for this chapter is available]

1. He then lays down a Viśvajyotis (all-light brick). Now the middle Viśvajyotis is Vāyu[1], for Vāyu (the wind) is all the light in the air-world: it is Vāyu he thus places therein. He places it so as not to be separated from the regional (bricks): he thus places Vāyu in the regions, and hence there is wind in all the regions.

2. And, again, as to why he lays down the Viśvajyotis,--the Viśvajyotis, doubtless, is offspring (or creatures), for offspring indeed is all the light: he thus lays generative power (into that world). He places it so as not to be separated from the regional ones[2]: he thus places creatures in the regions, and hence there are creatures in all the regions.

3. [He lays it down, with, Vāj. S. XIV, 14], 'May Viśvakarman settle thee!' for Viśvakarman saw this third layer[3];--'on the back of the air, thee the brilliant one!' for on the back of the air that brilliant Vāyu indeed is.

4. 'For all up-breathing, down-breathing, through-breathing,'--for the Viśvajyotis is breath, and breath indeed is (necessary) for this entire universe;--'give all the light!'--that is, 'give the whole light;'--'Vāyu is thine over-lord,'--it is Vāyu he thus makes the over-lord of that (layer and the air-world). Having settled it, he pronounces the Sūdadohas over it: the significance of this has been explained.

5. He then lays down two Ritavyā (seasonal[4] bricks);--the two seasonal ones being the same as the seasons, it is the seasons he thus places therein.[Vāj. S. XIV, 15], 'Nabha and Nabhasya, the two rainy seasons,' these are the names of those two (bricks): it is by their names he thus lays them down. There are two (such) bricks, for a season consists of two months. He settles them once only: he thereby makes (the two months) one season. He places them on avakā-plants and covers them with avakā-plants[5]; for avakā-plants mean water he thus bestows water on that season, whence it rains most abundantly in that season.

6. Then the two upper ones, with (Vāj. S. XIV, I6), 'Iṣa and Ūrja, the two autumnal seasons,'--these are the names of those two (bricks): it is by their names he thus lays them down. There are two (such) bricks, for a season consists of two months. He settles them only once: he thereby makes (the two months) one season. He places them on avakā-plants, for the avakā-plants mean water: he thus bestows water before that season, whence it rains before that season. He does not cover them afterwards, whence it does not likewise rain after (that season).

7. And as to why he places these (four bricks) in this (layer),--this fire-altar is the year, and the year is the same as these worlds, and the middlemost layer is the air (-world) thereof; and the rainy season and autumn are the air (-world) thereof: hence when he places them in this (layer), he thereby restores to him (Agni) what (part) of his body these (formed),--this is why he places them in this (layer).

8. And, again, as to why he places them in this (layer),--this Agni (the fire-altar) is Prajāpati, and Prajāpati is the year. Now the middlemost layer is the middle of this (altar), and the rainy season and the autumn are the middle of that (year): hence when he places them in this (layer), he thereby restores to him (Agni-Prajāpati) what part of his body these (formed),--this is why he places them in this (layer).

9. There are here four seasonal (bricks) he lays down in the middlemost layer; and two in each of the other layers,--animals (cattle) are four-footed, and the middlemost layer is the air: he thus places animals in the air, and hence there are animals that have their abode in the air.

10. And, again, why there are four,--animals are four-footed, and animals are food; and the middle-most layer is the middle (of Agni's body): he thus puts food in the middle.

11. And, again, why there are four,--'antarikṣa' (air) consists of four syllables, and the other layers (citi) consist of two syllables; hence as much as the air consists of, so much he makes it in laying it down.

12. And, again, why there are four,--this Agni (altar), doubtless, is an animal: he thus makes the animal biggest towards the middle; whence an animal is biggest towards the middle.

13. There are here four Ṛtavyās, the Viśvajyotis being the fifth, and five Diśyās,--this makes ten: the Virāj consists of ten syllables, and the Virāj is food, and the middlemost layer is the middle;--he thus puts food in the middle (of the body). He lays them down so as not to be separated from the naturally-perforated one[6], for the naturally-perforated one is the vital air: he thus places the food so as not to be separated from the vital air. Subsequently (to the central brick) he lays them down: subsequently to (or upon) the vital air he thus places food.

14. He then lays down the Prāṇabhṛt[7] (bricks);--the Prāṇabhṛts (breath-holders), doubtless, are the vital airs: it is the vital airs he thus lays into (Agni's body). There are ten of them, for there are ten vital airs. He places them in the forepart (of the altar),--for there are these vital airs in front,--with (Vāj. S. XIV, 17), 'Protect my vital strength! protect mine up-breathing! protect my down-breathing! protect my through-breathing! protect mine eye! protect mine ear! increase my speech! animate my mind! protect my soul (or body)! give me light!'--He lays them down so as not to be separated from the seasonal ones, for the vital air is wind: he thus establishes the wind in the seasons.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

The three Viśvajyotis bricks, placed in (the fourth easterly place from the centre of) the first, third and fifth layer respectively, are supposed to represent the regents of the three worlds--earth, air and sky--which these three layers represent, viz. Agni, Vāyu and Āditya (Sūrya). See VI, 3, 3, 16.

[2]:

Though, properly speaking, the Viśvajyotis lies close to only one of the Diśyās, viz. the eastern one, it may at any rate be said to lie close to the range of the Diśyās. Here, too, the sense 'immediately after, not separated from them in respect of time,' would suit even better.

[3]:

See VIII, 3, 1, 4 with note.

[4]:

[5]:

As in the case of the live tortoise, in the first layer; see VII, 5, 1, 11 with note--'Blyxa octandra, a grassy plant growing in marshy land ("lotus-flower," Weber, Ind. Stud. XIII, p. 250).'

[6]:

That is to say, the three sets of bricks are not separated by any others from the Svayamātṛṇṇā.

[7]:

The ten Prāṇabhṛts are placed--five on each side of the spine--either along the edge of the altar, or so as to leave the space of one foot between them and the edge, to afford room for another set of bricks, the Vālakhilyās.