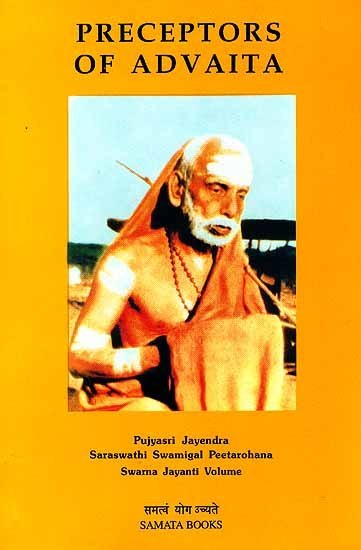

Preceptors of Advaita

by T. M. P. Mahadevan | 1968 | 179,170 words | ISBN-13: 9788185208510

The Advaita tradition traces its inspiration to God Himself — as Śrīman-Nārāyaṇa or as Sadā-Śiva. The supreme Lord revealed the wisdom of Advaita to Brahma, the Creator, who in turn imparted it to Vasiṣṭha....

24. Amalānanda

AMALANANDA

Rajesvara Sastri Dravid

Mahāmahopādhyāya

Śrī Appayya Dīkṣita, the most noteworthy and versatile Advaita scholar, in the beginning of his work Siddhāntaleśasaṅgraha observes:

“Victorious is the auspicious birth-destroying discourse (the Sūtrabhāṣya), which issues forth from the blessed lotus face of the Bhagavadpāda, has for its sole purport the non-dual Brahman, and is diversified a thousand-fold on reaching the (numerous) ancient preceptors (who expounded it), in the same way as the river (Gaṅgā), which issuing from the feet of Viṣṇu, is diversified on reaching different lands”

Ancient preceptors of Advaita who wrote commentaries and treatises on the Sūtrabhāṣya, of Śaṅkara with a view to determine its import were keen on establishing the unity of the self. And, in order to establish this, they advocated several theories which differ among themselves. All these differing theories, however, pertain only to the empirical stage, and hence they do not in any way stultify the non-dual nature of the self. Sureśvara, well-known as the author of the Vārtikas, states that by whichever theory one attains to the knowledge of Brahman that theory must be taken to be the best; and there are many theories within the fold of Advaita.

Among the manifold theories explored and expounded by the ancient preceptors, the theories advocated by Vāchaspatimiśra in his commentary, Bhāmatī, on the Sūtrabhāṣya of Śaṅkara are prominent His work is traditionally known as the Bhāmatīprasthāna. He wrote treatises on the six orthodox darśanas, and was well-versed in Nyāya, Mīmāṃsa and Vyākaraṇa. The word prasthāna etymologically derived means a work by which is determined (sthīyate-nirṇīyate) beyond all uncertainty (prakarsheṇa) the import of the Sūtrabhāṣya of Śaṅkara. The work Bhāmatī determines beyond all uncertainty the import of the Sūtrabhāṣya of Śaṅkara and hence it is called a prasthāna.

The views set forth in the Bhāmatī are difficult to understand and, in order to favour the earnest students of Advaita, Śrī Amalānanda wrote a commentary on it by name V edāntakalpataru. Śrī Appayya Dīkṣita in his Parimala on the Vedāntakalpataru says that the latter gives room, like the aerial car of Puṣpaka, to the manifold theories set forth by wise men. We shall now set forth briefly some unique features of the Kalpataru in the interpretation of the Bhāmatī on the Chatussūtrī portion of the Sūtrabhāṣya.

Śrī Śaṅkara in his adhyāsabhāṣya states, ‘After imposing on each the nature and the attributes of the other through non-discrimination of each from the other in the case of attributes absolutely distinct among themselves as also of the substrates absolutely distinct among themselves, there is this natural empirical usage like, “I am this”, and “this is mine”, coupling the true with the untrue, with its cause in the illusory cognition’.[1]

The Bhāmatī on this passage is as follows: The true is the intelligent self; the untrue are the intellect, the sense-organs, the body, etc.; coupling (mithunīkṛtya) these two substrates; coupling means yoking (yugalīkṛtya),[2]

Although the word mithunīkṛtya is interpreted in the sense of yugalīkṛtya, yet the intended sense is not clear. A doubt naturally arises whether this yugalīkaraṇa means the relations of contact, etc., or a unique kind of relation.

Amalānanda in the Kalpataru explains the word “yugalīkaraṇa ” .thus: The manifestation of the substrate and the object superimposed is yugalīkaraṇa.

“yugalīkaraṇam nāma adhiṣṭhānāropyayoḥ svarūpeṇa buddhau bhānam.”

This definition has one difficulty. Yugalīkaraṇa is the cause of superimposition. And, it is interpreted to mean the manifestation of substrate and the object superimposed. The latter, therefore, necessarily precedes superimposition. But, before the first superimposition of mind on the self, when one gets back to waking state from deep sleep or at the time of first creation when the cosmic dissolution is over, the manifestation of the substrate and the object superimposed, that is, mind, is not possible. For, it is admitted that at the time of dissolution or deep sleep mind merges in its cause that is, avidyā. Hence it must be held that the latent impressions arising out of the manifestation of the substrate and the object superimposed (mind) before the dissolution or deep sleep is the cause of the superimposition of mind on the self when one gets back to waking state from deep sleep or at the time of the first creation when the cosmic dissolution is over. Yugalīkaraṇa thus comes to mean the latent impressions arising out of manifestation of the substrate and the object superimposed. The manifestation of the substrate and the object superimposed is superimposition. Hence yugalīkaraṇa means the latent impressions of the earlier superimposition.

Yugalīkaraṇa, therefore, means the latent impressions of the earlier superimposition which has for its content the substrate and the object superimposed and whose form is identical with the form of the succeeding superimposition.

adhyāsasamanākāraḥ adhiṣṭhānāropyaviṣayakaḥ

pūrvabhramasaṃskāraḥ yugalīkaraṇamityarthaḥ.

It has been said that yugalīkaraṇa means manifestation of the substratum and the object superimposed. From this it should not be understood that there is the manifestation of the substrate and the superimposed object as distinct entities. According to Advaita, error is not admitted without a substratum. What is superimposed is unreal. And it has no existence independent of the substratum. Substratum is the limit of sublation. And by its knowledge, the knowledge of the superimposed object is sublated or at least taken to be not valid. So when it is said that there is manifestation of the substratum and the object superimposed, it must be understood that the two are manifest as a blend or a unified whole.

Now it might be objected thus. The manifestation of substratum and the object superimposed as a unified whole is error or superimposition. It is the cause of later superimposition. The knowledge of the substratum is independently the cause of the knowledge of the substratum of the later superimposition. Similarly the knowledge of the superimposed object is independently the cause of the knowledge of the superimposed object of the later superimposition. One need not hold that the form of the earlier superimposition or its latent impression as such is the cause of the later superimposition and must correspond to the form of the later superimposition.

This objection is not valid. One does not have the erroneous cognition in the form of ‘I am the body’ (aham dehaḥ) although there exists the knowledge ‘aham’ and ‘dehaḥ’ separately. The reason is that there is no such previous knowledge and so no such latent impression which could lead to the superimposition in the form of ‘I am the body’. On the other hand, there is the superimposition in the form of ‘I am a man’, and this is caused by the previous superimposition or its latent impression in the form of ‘I am a man’. Hence the form of the later superimposition corresponds to the form of the earlier superimposition or its latent impression. And, the earlier superimposition or its latent impression by having a form similar to that of the later superimposition is the cause of the later superimposition. Hence yugalīkaraṇa means earlier superimposition or its latent impression.

In the adhyāsa-bhāṣya Śaṅkara says: There is this natural empirical usage like ‘I am this’, and ‘This is mine’. The Bhāmat ī on this passage is as follows: ‘When there is cognition of what is superimposed, there is the superimposition of what was formerly seen, while that cognition itself is conditioned by superimposition; thus, (the defect of) reciprocal dependence seems difficult to avoid. To ibis he says: “natural”. This empirical usage is natural, beginningless. Through the beginninglessness of the usage, there is declared the beginninglessness of its cause—superimposition. Hence, of the intellect, organs, body, etc., appearing in every prior illusory cognition, there is use in every subsequent instance of superimposition. This (process) being beginningless, like (the succession of) the seed and the sprout, ‘there is no reciprocal dependence; this is the meaning’.

From this it is dear that the empirical usage, its cause, that is, superimposition, and its cause, earlier superimpositions or the latent impressions—all these are beginningless like a stream. Amalānanda explains the concept of beginninglessness in the following verse:

tadākṛtyuparaktānām vyaktīnāmekadhā vinā

anādikālāvṛttiḥ yā sā kāryānāditā matā.

Earlier superimpositions or their latent impressions are beginningless in this sense that there always exists the relation of time to either of these. In the same way, adhyāsa or superimposition is beginningless in the sense that superimposition or its subtle form is always related to time. Similarly, empirical usage is beginningless in this that empirical usage or its subtle form is always related to time.

Some hold that this series of superimpositions or their laten t impression is avidyā. And they cite the following texts from the Sūtrabhāṣya to substantiate their contention.

One text is:

“Wise men consider the superimposition of this nature to be avidyā”;[3]

and the other text is:

“It is for the removal of this cause of evil, for the attainment of the knowledge of the oneness of the self, that all the Vedāntas are commenced”.[4]

On the basis of these texts, some conclude that the Bhāmatī which speaks of two kinds of nescience in the invocatory verse is not true to the view of the Sūtrabhāṣya.

In order to remove this misapprehension the Kalpataru states that one kind of nescience which is beginningless and positive in character is explained in the devatādhikaraṇa; and the other kind is the series of latent impressions arising from previous erroneous cognitions. Between these two kinds of nesdence, the one that is explained in the devatādhikaraṇa is well-known in the Advaita literature to be the mūlāvidyā, primal nescience.

Now two questions arise, one as to the nature of nescience and another as to its primal nature. Nescience is that which has undifferentiated consciousness alone as its content (viṣaya). And it is avidyā in the sense that it is removable by the intuitive knowledge of Brahman. Or, we may say that it is avidyā in the sense that it has the characteristic of veil i ng the true nature of Brahman. And this characteristic of veiling the true nature of Brahman is present both in the mūlāvidyās and the tūlāvidyās. It is a jātiviśeṣa; and it gives rise to the empirical usage ‘I do not know’. Its primal nature consists in this that it is the material cause of the superimposition of the body, the senses, etc., by veiling the true nature of the substratum. The phrase “material cause of erroneous cognition (bramo’pādāna)” occurring in a Kalpataru passage conveys the sense that mūlāvidyā is the material cause of superimposition by veiling the true nature of the substratum.

Now an objection may be raised. The superimposition of the body, senses, etc., is like a continuous stream and so the earlier superimposition is the cause of the succeeding one. When such is the case there is no necessity to resort to primal nescience as the cause of superimposition.

This objection does not hold good. Primal nescience serves a two-fold purpose. One is that it conceals the specific nature of the substratum of superimposition. There arises the superimposion of silver in the nacre only when the specific nature of the substratum, that is, the consciousness delimited by nacre is not manifest. It is an invariable rule that non-manifestation of the specific nature of the substratum is the most important cause of superimposition. The phrases like vivekāgraha, and asaṃsargāgraha refer only to the non-manifestation of the specific nature of the substratum. When there is the manifestation of the specific nature of the substratum, there does not arise superimposition. The chief reason for this is that there is the absence of the cause of the superimposition, that is, non-manifestation of the specific nature of the substratum. Thus, only when there is the nonmanifestation of the specific nature of the undifferentiated consciousness, could the superimposition of mind, etc., on the self arise. And, the non-manifestation of the specific nature of Ātman is caused only by mūlāvidyā. In this sense it is the cause of the superimposition of mind, etc., on the self and the relation of the self on the mind, etc.

Another purpose is served by mūlāvidyā. It is the transformative material cause of the superimposition of the body, senses, etc. It is thus: The superimposition of the body, senses, etc., has a transformative material cause, because it is an existent effect, like pot, etc. Thus is assumed only one transformative material cause with reference to all superimpositions. It is similar to the Naiyāyika position that only one omniscient being, that is, God, is inferred to be the efficient cause of the entire universe. The Upaniṣadic text ‘māyām tu prakṛtim vidyāt māyinam tu maheśvaram’ affirms avidyā to be the primal cause of the universe.

Although Madhusūdanasarasvatl and Brahmānandasarasvatī established the validity of the Advaitic truth by adopting the Navya-nyāya method, yet it must be noted that they adopt the line of arguments of the Kalpataru and other commentaries. And this is evident from this that both the writers often refer to the views of the Kalpataru in their works.

There is a bhāṣya text which is as follows:

“There is begun respectful enquiry into the Vedānta texts whose auxiliary is reasoning not inconsistent therewith and whose purpose is liberation”.[5]

The Bhāmatī on this passage is as follows:

“The enquiry, into the Vedānta is itself reasoning; other reasoning which does not conflict therewith such aś is mentioned in the Pūrvamīmāṃsā and the Nyāya-sūtras in discussing the authoritativeness of the Veda, of perception, etc., serves as auxiliary”.[6]

The Kalpataru on the above passage comments that the Nyāya-śāstra, Smṛtis, etc., are said to be ‘reasonings’ (tarkāḥ) in this that they are auxiliaries to the understanding of the import of scripture.

Thus the Navya-nyāya terminology also must be taken to be ‘tarka’ and it is part and parcel of the Vedāntamīmāṃsā. And the later Advaitic writers adopted the Navya-nyāya method in their works in order to achieve logical precision.

Amalānanda at the end of the Kalpataru says that he wrote the work under the Yādava king of Devagiri (the present Doulatabad)—Kṛṣṇa and his brother Mahādeva (1247-1260 A.D.). Hence Amalānanda flourished in the middle of the 13th century.

In the beginning of the Kalpataru on the third chapter of the Brahma-sūtra, Amalānanda gives his name as Vyāsāśrama.

“śrīmad vyāsāśramasya prativadanamadāt karṇayugmam viriñchiḥ ”.

In the beginning of the Kalpataru, Amalānanda says that he is the disciple of Śrī Anubhavānanda.

“yathārthānubhavānanda-padagītam gurum namaḥ ” .

He further states that Śrī Ātmānanda-yati is his grand-preceptor.

“ātmānandayatīśvaram tam aniśam vande gurūṇām gurum.”

And his vidyāguru is Sukhaprakāśa, the disciple of Chitsukha.

“prodyat-tāraka-divya-dīpti-paramām vyomāpi nīrājyate,

gobhīrasya sukhaprakāśaśaśinam tam naumi vidyāgurum ”.

Amalānanda lived in Nasik-trayambaka-kṣetra. In the Samanvayādhikaraṇa there occurs the following verse in the Kalpataru.

“asti kila brahmagiri nāma girivaraḥ

trayambakajaṭājūṭakalanāya vinirmitā

pāṇḍureva paṭī bhāti yatra godāvarī nadī.”

While commenting on this, Śrī Appayya Dīkṣita states that our author who lived in Nasik-trayambaka-kṣetra composed his works. Apart from the Kakpataru on the Bhāmatī , Amalānanda wrote Śāstradarpaṇa an exposition on the Brahma-sūtra.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

tathāpi anyonyasmin anyonyātmakatām anyonyadharmāṃścha adhyasya itaretarāvivekena atyantaviviktayoḥ, dharmadharmiṇoḥ mithyājñānimittaḥ satyānṛte mithunīkṛtya ahamidam mamedamiti naisargiko’yam lokavyavahāraḥ.

[2]:

satyam chidātmā, anṛtam buddhīndṛyadehādi, te dve dharmiṇi mithunīkṛtya yugalīkṛtya ityarthaḥ

[3]:

asya anarthahetoḥ prahānāya ātmaikatva-vidyāpratipattaye sarve vedāntāḥ ārabhyante.

[4]:

There is a tradition that the Pañchadaśī is the joint work of Bhāratītīrtha and Vidyāraṇya. Another view is that it is the work of Bhāratītīrtha who also bore the title ‘Vidyāraṇya’.

[5]:

vedāntavākyamīmāṃsā tadavirodhitarkopakaraṇā niśreyasaprayojani prastūyate (Sūtrabhāṣya on i, i, 1).

[6]:

vedāntamīmāṃsā tāvattarka eva, tadavirodhinaścha ye anyepi tarkāḥ adhvaramīmāṃsāyām nyāye cha vedapratyakṣādiprāmāṇyapari-śodhanādiṣūktāh te upakaraṇam yasyāḥ sā tathoktā;