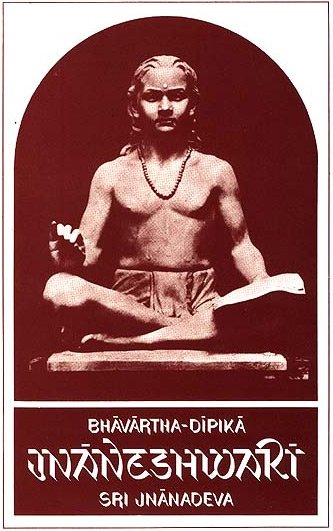

Jnaneshwari (Bhavartha Dipika)

by Ramchandra Keshav Bhagwat | 1954 | 284,137 words | ISBN-10: 8185208123 | ISBN-13: 9788185208121

This is verse 18.1 of the Jnaneshwari (Bhavartha-Dipika), the English translation of 13th-century Marathi commentary on the Bhagavad-Gita.—The Dnyaneshwari (Jnaneshwari) brings to light the deeper meaning of the Gita which represents the essence of the Vedic Religion. This is verse 1 of the chapter called Moksha-sannyasa-yoga.

Verse 18.1

Verse 18.1: “Of Renunciation, O Long-armed One, I want to know the real essence; and of Relinquishment, O Hrishikesha (Krishna): (each) severally, O Slayer of Keshin.” (87)

Commentary called Jnaneshwari by Jnaneshwar:

In truth ‘Renunciation’ and ‘Relinquishment’—both these words convey only one meaning, in the way both “Samghata” and ‘Sangha’ mean only what is called ‘Samghata’ (saṃghāta—Union). In that way, as I understand, Relinquishment and Renunciation mean only what is called relinquishment (tyāga). However, if there be any distinction in the meaning of these two, O God, do please clarify it. At this Shri Mukunda said, that they do have distinct meanings. (God further said), “I do believe, O Arjuna, that to your mind relinquishment and renunciation appear to have one and the same meaning. It is a fact that both the words convey the sense of relinquishment: but the only reason for the distinction is that discarding activism in toto is renunciation, while abandoning only the fruit of action is relinquishment.

Now I shall preach clearly to you and do hear attentively about the actions in which only the action-fruit should be relinquished and of others in which actions themselves should be relinquished. Abundant and limitless free growth takes place in woods and jungles on mountains, without anyone growing any plantations there. Rice and garden trees do not however grow in that way (they have got to be planted). There takes place a rank growth of grass without any sowing: yet the rice seedlings do not sprout until the soil is first burnt with the help of loppings, leaves, grass and rubbish before sowing and then the seed is sown etc.: or the human body develops naturally, yet the ornaments (to be donned) are required to be manufactured: or a river flows its natural course, yet a well is required to be sunk. In that way the routine day-to-day and occasional actions take place in the natural course and when done without any fruit-motive, they do not become fruit-motived (kāmika), (and do not also fetter the doer).