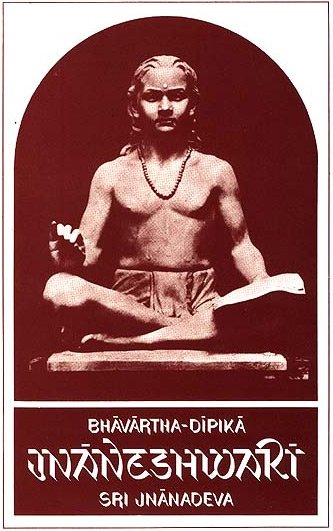

Jnaneshwari (Bhavartha Dipika)

by Ramchandra Keshav Bhagwat | 1954 | 284,137 words | ISBN-10: 8185208123 | ISBN-13: 9788185208121

This is verse 16.3 of the Jnaneshwari (Bhavartha-Dipika), the English translation of 13th-century Marathi commentary on the Bhagavad-Gita.—The Dnyaneshwari (Jnaneshwari) brings to light the deeper meaning of the Gita which represents the essence of the Vedic Religion. This is verse 3 of the chapter called Daivasura-sampad-vibhaga-yoga.

Verse 16.3

Verse 16.3: “High spirit, forbearance, Sustaining power, Purity, Absence of malice, and Freedom from excessive Self-conceit: these belong to one who is, O Scion of Bharata, born to the Divine Estate. (186)

Commentary called Jnaneshwari by Jnaneshwar:

One with a firm mind proceeding along the path of knowledge with a view to attaining the Supreme, never feels the want of strength. Death is in itself a great evil and the more so if it is to be accomplished through the agency of fire (auto-da-fe), yet a Sati (a loyal and virtuous wife) takes no count of it (since it is a sacrifice) for the sake of her husband. In that way the being, out of anxious desire for attaining the (supreme) self, first destroys the poison in the form of sense-objects and then runs along the difficult path in the form of concentrated meditation leading to the great void Brahman (śūnya). He is neither deterred by protests nor does he Waver on account of any precepts, nor yet does there arise in him any longing for occult powers (mahāsiddhi). In that way, of its own accord, his mind runs towards the Supreme and this is what is called ‘spiritual fervour’ (teja). Now not to feel any conceit being the highest (quality) amongst those bearing this disposition, is called ‘forbearance’ (kṣamā).

There are thousands of hairs on the body; yet the body does not even know that it is carrying their weight: wild passions (generated by the senses) get out of control, or the old dormant diseases in the body raise their heads, or one is confronted with the separation of dear and near ones, or the association with undesirable ones—if the mighty and simultaneous flood of such calamities overtakes one, he stands out firm and fast unperturbed like the sage Agastya. There should rise up a big column of smoke in the sky and it should be easily gulped by a single breeze of wind; similarly, should there simultaneously arise, Oh son of Pandu, the three classes of affliction viz. corporal, physical and supernatural these should be swallowed and digested. To take courage and stand steadfast on such occasions of mental perturbation is called ‘sustaining power’ (dhṛti), hear this, Oh ye (Arjuna).

(Now about ‘Purity’—śaucya). (It is like) a burnished gold pot filled with nectar in the form of the water of the Ganges. Taking to motive-free activism and conducting oneself with discrimination—is the inner and outer form of purity. The holy water of the Ganges while flowing to join the sea, cools down the heat (pain) arising out of the sins of beings, and also provides moisture to the trees on the banks: or the sun while on his rounds around the earth removes the blindness (darkness) in the world, and also opens out the temples of riches. In that way, (he) liberates the fettered ones, takes out the drowning ones and relieves the sufferings of the distressed. Nay, he secures his own end, while advancing day and night, the happiness and prosperity of others. He never even conceives the idea of doing any harm to other beings to secure his own ends. These are the signs of ‘absence of hatred’ (adrohatva), which you have heard so far, Oh Kiriti, and you will be able to view them in the same light as I have preached you. The holy Ganges felt abashed (saṅkoca [saṃkoce]) when Lord Shankar bore her (it) on his head, Oh Arjuna; feeling abashed in that way when honoured, know ye, Oh Good Talent, again and again, is that freedom from self-conceit (amānitva) of which I spoke to you earlier and I shall not repeat the same.

These twenty-six qualities thus con-stitute the ‘Divine Estate’, which forms, as it were, the hereditary gift (agrahāra—villages or lands assigned to Brahmins for their maintenance) given by the Lord Paramount in the form of emancipation: or the Divine Estate should be looked upon as the Ganges ever full with holy waters in the form of the (twenty-six) qualities, luckily sweeping over the bodies of the sons of King Sagara in the form of asceticism; or as if the maiden (bride) in the form of liberation, with a floral wreath in her hands, is on the look-out for a tranquil ascetic around whose neck she wishes to place it: or as if the wife in the form of Gita, with a lamp (nirāñjana) having (twenty-six) flames in the form of (twenty-six) Gunas, has come to wave it (lamp) around the face of her Lord the (Supreme) Soul; or as if these qualities are pure unspotted pearls (dropped down) from the mother-of-pearl in the form of the Divine Estate and churned out of the ocean in the form of Gita. To what length should I describe it further? I have preached the Divine Estate, a heap of (twenty-six) qualities, so lucidly that it would be easily realised.

Now the ‘Demoniacal Estate’, even though a creeper plant full of miseries and thorns in the form of demerits, has got to be discoursed on in the course of a sermon. A thing, even though of no use and only fit to be abandoned, must be known, in order that it might be abandoned. Even though full of evil it is proper to hear about it attentively. This ‘Demoniacal Estate’ is a veritable collection of dreadful demerits (since) lumped together to constitute the great misery of life in hell: or all the poisons blended together from what is known as the deadly poison (vāsaṭu) in that way the big assemblage of all sins brought together is (named) the “Demonical Estate”.