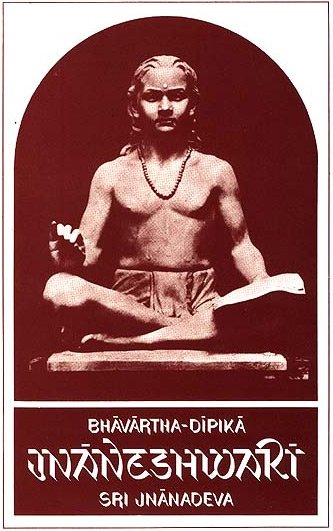

Jnaneshwari (Bhavartha Dipika)

by Ramchandra Keshav Bhagwat | 1954 | 284,137 words | ISBN-10: 8185208123 | ISBN-13: 9788185208121

This is verse 14.24 of the Jnaneshwari (Bhavartha-Dipika), the English translation of 13th-century Marathi commentary on the Bhagavad-Gita.—The Dnyaneshwari (Jnaneshwari) brings to light the deeper meaning of the Gita which represents the essence of the Vedic Religion. This is verse 24 of the chapter called Gunatraya-vibhaga-yoga.

Verse 14.24

Verse 14.24: “Even (-poised) in woe and weal, stabilised in self, holding equal a clod, a stone, or gold; putting the loved and the unloved on the same level: the man of wisdom whom censure and personal commendation affect alike: (349)

Commentary called Jnaneshwari by Jnaneshwar:

Just as there is nothing else in the fabric, Oh Kiriti, but yam in and out, so he (man of knowledge) sees that there is nothing else in the entire universe but my own ‘Self. Lord Hari makes gifts in equal proportions both to foes and friends; in the same way he, like a balance with two pans treats equally both pleasure and pain. Normally the being must experience pleasure and pain while going about in the body—form, in the way the fish does in the water. But he, (the man of knowledge) has dropped it all (all feelings, etc. in regard to body) and has attained unto Supreme Self. The grain inside (seed) becomes visible when the external chaff is removed; or the rippling (noise), the hurry and the bustle of a river-flow, subside as soon as the river falls into the sea. In that way, Oh Dhananjaya, in the case of one who has attained unto Supreme Self, the pleasure and pain automatically abide quietly in the body without making their presence felt in any way. Day and night are both treated alike by a pillar in the house. In that way the embodied one who has already become one with Supreme Self, treats alike all pairs of opposites (like woe and weal, etc.).

The bodily contact with a serpent or Urvashi (the Heavenly nymph) are both one and the same to one in deep slumber, in that way the bodily duals pairs of opposite sentiments (dvandva [dvandveṃ]) such as pleasure and pain etc. are one and the same to one that has become one with the Supreme Self. The vision of such a one makes no distinction between an animal dung and gold and between gems and pebbles. His Brahmic equanimity (even-poised self) is never disturbed were the very Heavens to visit his house or a ferocious tiger to raid it. The evenness of his temper never gets ruffled in the way a corpse cannot rise up again or the baked seed cannot germinate. Whether praised as God Brahmdeo [Brahmadeva?] or slandered as one base, he remains (as unaffected as) a mass of ashes neither burning nor getting extinguished. Similarly neither slander nor praise (of any one else) emerges out of him in the way there is neither darkness nor a lighted lamp (wick) in the house of the Sun.