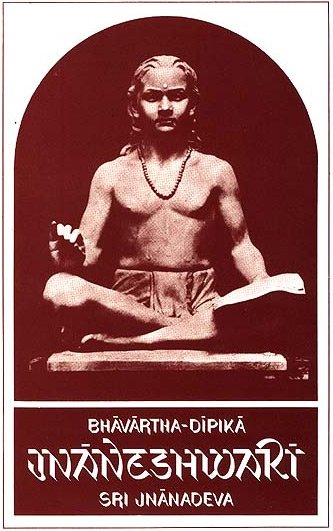

Jnaneshwari (Bhavartha Dipika)

by Ramchandra Keshav Bhagwat | 1954 | 284,137 words | ISBN-10: 8185208123 | ISBN-13: 9788185208121

This is conclusion of chapter seven of the Jnaneshwari (Bhavartha-Dipika), the English translation of 13th-century Marathi commentary on the Bhagavad-Gita.—The Dnyaneshwari (Jnaneshwari) brings to light the deeper meaning of the Gita which represents the essence of the Vedic Religion. This is verse Conclusion of chapter seven of the chapter called Jnana-vijnana-yoga.

Conclusion of chapter seven

But while Lord Krishna was pouring out the juicy oration from the bottle in the form of these words, the cavity formed by joining the two palms (ajulī) [añjulī/añjali?] in the form of Arjuna’s attention did not move forward to receive it, since Arjuna’s mind was still lingering behind on the preceding portion. As the fruit in the form of the word on Supreme Brahman overflowed with juice in the form of deep meaning, and spreading all around its fragrance in the form of good feelings, dropped down at the gentle breeze of grace, into the four mouthed-bag (kholī) of Arjuna’s ears, from the tree in the form of Lord Krishna’s person, it was felt as if they (fruits) were formed out of great established eternal truths (siddhānta) or were dipped in the ocean of Supreme Divine Knowledge, or were rolled over and over again in the Supreme bliss. Their sweet charm made Arjuna’s vision to take in gulps of nectar in the form of (pleasant) ecstatic wonder. As he enjoyed this taste of that Supreme happiness Arjuna even mocked and mouthed (vākuliyā) at those enjoying Heavenly paradise, while his heart was suffused with great joy.

Then Arjuna felt an intense longing for tasting the juice of the fruit in the form of divine words, since the beauty of the mere external vision of it made his happiness overflow itself. Therefore, hastily taking in the hand of his Intuition, the fruit in the form of Lord Krishna’s words, he (Arjuna) put it at once into his mouth of inmost experience. But the tongue in the form of intellect could not relish it, while the teeth in the form of reason found it hard to crack it. At this, the husband of Subhadra (Lord Krishna’s sister) left off even sucking it.

Getting surprised, he said to himself,

“Are these (merely) the glittering reflections in water of the stars? How have I got deceived by the external make-up of the syllables? What sort of letters are these? They appear to be mere folds of the sky; my intellect would not be able to get any trace of anything, were it even to take a jump however high. How would I be able to know anything about it, unless I get any trace of it?”

With such thoughts Kiriti once again turned his eyes towards Lord Krishna, the Lord of Yadavas, and resquested him,

“Oh God, these seven (Brahma, Karma, Adhyatma and others) words put together are untasted and unique, Otherwise, could these great truths have remained unsolved even after being heard with concentrated attention? But this is not a thing of that sort. Even surprise got greatly amazed seeing this string of words! I am startled and my mind is cut into two, no sooner than the rays of the words reached my heart through the windows of ears. I have a great liking for hearing the meaning, but there is no time even to speak that out. So God, proceed with the discourse immediately.”

Just see, how adept is Arjuna in his way of asking questions viz. first making sure of the ground already covered and keeping his gaze further on the end and meanwhile mentioning also his great love for the theme; and never did he overstep the limits of scrupulous modesty. Otherwise, he would have outstretched his arms and held Lord Krishna in an embrace. Arjuna alone knew that that was the only respectful approach in putting questions to the Preceptor. Now the hearers should turn to the very charming manner, in which Samjaya will speak of Arjuna’s question and Lord Krishna’s reply to it. This will all be told, in simple, plain Marathi so that the eyes have a vision of the meaning even before the ears grasp it. All the senses are lured by the beautiful shape of letters, even before the tongue of intellect tastes the sweet juice of meaning in the heart of the letters. Just see: not only that the buds of the flower-plant Malati (mālatī) please the nostrils with their fragrance, but the outward beauty of their colour does also please the eye. In that way the beauty of the Marathi language blesses the senses with the power to make a conquest of Bliss and may then enter the dwelling place of eternal truths.

Thus prays Jnanadev of Nivrittinath:—“Do listen to my talk of beautiful words that silences all talk.” (210)