Early Chola Temples

by S. R. Balasubrahmanyam | 1960 | 105,501 words

This volume of Chola Temples covers Parantaka I to Rajaraja I in the timeframe A.D. 907-985. The Cholas of Southern India left a remarkable stamp in the history of Indian architecture and sculpture. Besides that, the Chola dynasty was a successful ruling dynasty even conquering overseas regions....

Preface

South Indian architecture and sculpture has been comparatively neglected till recent times. But it is coming into its own and slowly but surely its greatness has begun to be recognised both in India and abroad. To Jouveau Dubreuil, a pioneer in this field of study, we owe much, while Gopinatha Rao, the Iconographer, also contributed very considerably to our knowledge of the subject though in a specialised context. Closer to our own generation is the work of Professor Nilakanta Sastri and of S.R. Balasubrahmanyam, the author of the present volume. A factor of prime importance in the study of South Indian architecture and sculpture is the wealth of inscriptional material on the walls of South Indian shrines. This vast engraved documentary provides a veritable ocean of knowledge for the history, the social and economic life, the religion and religious practices, the iconography and the town and village administration of South India. Though the method of stylistic analysis for the study of South Indian art must ever remain of high importance, the inscriptional evidence is not only an invaluable handmaiden to a scholar of this subject but often the key to the solution of knotty problems and controversial opinions. But it is not given to many to be able to correctly read and interpret this source material in Pallava-grantha and Tamil. Shri Balasubrahmanyam has the good fortune to be one of those few who can, with authority, expound this inscriptional material. No scholar of South Indian inscriptions would be slow to recognise this fact even where differences of opinion exist, as they must, in so specialised a subject of scholarship. Not only are these inscriptions beset with many difficulties pertaining to their date and interpretation, but the material, being immense, has to be collated with the help of known historical facts, obtained from other sources such as copper plate grants and contemporary literature remembering ever the regnal periods of different kings. Birudas such as Rajakesarivarman and Parakesarivarman can often be misleading as they apply to more than one ruler. It is not uncommon to find that it is only by a process of correctly eliminating various discordant aspects that one can arrive at reasonably certain conclusions. One outstanding feature of the present volume is that the author while putting forward his interpretation of an inscription enables the reader to know what other eminent epigraphists also have to say on disputed points. These temple inscriptions, apart from those which the author himself has discovered, are published in a large number of scattered reports and the author has placed all students of South Indian art under a great debt in bringing together all relevant inscriptions pertaining to a particular shrine in relation to the period covered by the present study. In addition, Shri Balasubrahmanyam has carefully noted the architectural development of the South Indian temple from reign to reign and combined this study with the inscriptional evidence in order to justify the sequence which he has sought to establish as well as his ascription of the foundation or renovation of a particular temple to a particular reign. The result we may say without any undue praise is an indispensable source book for the study of the South Indian temple from the time of Parantaka I to the end of the reign of Uttama Chola. South Indian temple art covers an enormous canvas right from the early cave architecture of the Pallavas, the Pandyas and the Vishnu-kundins upto the mighty bizzare fanes of the Vijayanagar rulers and their viceroys the Nayaks. To the author, the crest-jewel of this glittering complex is the temple art of the Chola kings. His first volume on this subject was limited to the reigns of Vijayalaya and Aditya I and the present volume is its sequel. Of Aditya I it is said in the Anbil plates of Sudara Chola that he constructed numerous temples of stone to Lord Shiva on both banks of the Kaveri river. This was not an empty boast for “Early Chola Art” by Shri Balasubrahmanyam is a twentieth century revealment of this glorious achievement. But the successors of Aditya I were not slow to emulate the piety of their famed ancestor and the present volume is the result of painstaking research spread over many places and many years to tell us of what was contributed for the advancement of early Chola temple art by Parantaka I, Sundara Chola, Aditya II and Uttama Chola. In this period come the remarkable endowments of Sembiyan Mahadeviyar, the mother of Uttama Chola whose religious zeal, though expressed in a different manner, reminds us of the fervour of the Shaivite gospellors of an earlier age who revolutionised the religious life of the South. The Sembiyan age which the author deals with in considerable detail is a humble tribute to an inspired devotee of the Lord. Some of the noblest South Indian bronzes were the creation of the Sembiyan age.

There is no aspect of Indian art which is not controversial today. The reconstruction of oft inadequate or disputed material leads to differing conclusions at the hands of scholars. This is also true with regard to early Chola temple art though the solid body of inscrip-tional evidence which has been patiently brought to light by Epigraphists, including the author, tends to narrow down differences of opinion. But some measure of disagreement will remain. The method adopted by the author covers the temples in each reign setting out the location, the relevant inscriptions and certain stylistic features. Those who are aware that inscriptions from older foundations were often copied out on to later reconstructions will realise the difficulties which beset the researcher. Whether particular inscriptions are original or copies can at times be a vexed question. Shri Balasubrahmanyam is alive to the problem but it is natural that so competent an epigraphist must have his own views on such matters. Where general agreement is not possible, each scholar must work out his own solution and support it to the best of his ability. Differences of opinion make a thesis neither good nor bad. If the discussion of contrary viewpoints affords an impetus to re-thinking then it is worthwhile. No true scholar can afford to be inflexible if the object of scholarship is the search for truth. That some parts of this volume deal with controversial matters is evident from the fact that the author himself has controverted certain viewpoints held by other writers. Notably I may refer to the Tiru Alandurai Mahadevar temple at Kilappaluvur. Its construction has been assigned by Barrett to the fifteenth regnal year of Uttama Chola and the style of its devakoshta sculptures has been relied on in part for this conclusion. Apart from the fact that there are only five devakoshta sculptures which would ordinarily suggest a period earlier than Uttama Chola, the style of the sculptures does not to my mind preclude a dating in the reign of Parantaka I which in fact has been suggested by Shri Balasubrahmanyam. The temple has an inscription of Parantaka I as early as his tenth year and no convincing data is forthcoming to regard the Parantaka I inscriptions as later copies engraved on a new shrine of the fifteenth year of Uttama Chola. I see no real difficulty in regarding the Lingodbhavamurti of the Tiru Alandurai Mahadevar temple as belonging to the Parantaka I period and similarly if one does not doubt that the Brahma of the temple at Uyyakkondan Tirumalai very close to Trichy belongs to the Parantaka period, then the Brahma of Tiru Alandurai can equally well be placed in the same period. Though I am a great believer in the method of stylistic analysis, I am not inclined to put too much reliance on minor iconographic details. For instance it was at one time thought that the presence of a kirthimukha buckle on a waist belt in a South Indian bronze precluded it from belonging to the Pallava period. But as I have shown elsewhere this type of buckle, though in less elaborate manner, is found both in the Kailasanatha temple and Vaikuntha Perumal temple at Kanchi and is not uncommon in late Pallava sculpture even in a more elaborate form. Again there is considerable difference of opinion on the date of the Muvarkoyil of Kodumbalur which Shri Balasubrahmanyam confidently ascribes to the reign of Sundara Chola. But I must content myself with saying that a Preface is not the proper forum for the elucidation of intricate historical details.

Since my primary interest in Chola art is the sculpture of that age (both stone and metal), it is satisfying to observe that the author has not bypassed these two most important aspects of Chola achievement. But any study of Chola sculpture must begin with that of Pallava sculpture for the debt of the Cholas to later Pallava art is very great indeed. It is a cardinal error to think of later Pallava sculpture as a process of decline. Kaverippakkam, Tiruttani, Takkolam, Rama-krishnarajpet and several other sites in the same tradition as this close knit complex must dispel all notions of the decline of Pallava art. In fact it was the work of this period which gave the initial impetus to the early Chola art of Adityal and its inspiration persisted even into the reign of Parantaka I. Though sculptures and bronzes are not the principal themes of the present volume, yet the inscrip-tional material collated by the author will also afford invaluable guidance to the dating of Chola sculpture of various periods. Of course much caution has to be exercised because sculptures of a later period have come to be placed in earlier temples and vice versa. The author has however enumerated all the early sculptures still existing in each temple or its precincts and also indicated as far as possible, which of them are clearly later insertions of another period. Where new niches have been cut, this can be observed, but replacements in old devakoshtas require very detailed examination. The position with regard to metal images is even more difficult. Here we can rarely secure the aid of inscriptional material and a stylistic sequence has to be worked out utilising stone sculpture as a most useful but not invariably correct mentor. The author appropriately deals with Dubreuil’s theory of the Chakra and Sankha which pointed out long ago could not be accepted as a sure guide though it undoubtedly has its uses. So also, the position of the Yajnopavita in conjunction with other stylistic factors can still be a very useful indication to the period of a particular sculpture or bronze. This is also true of the different formations of the hanging median loop of the waist girdle. Nevertheless it is true that no cut and dry methods can be evolved for establishing a chronological sequence of Chola sculpture and metal images.

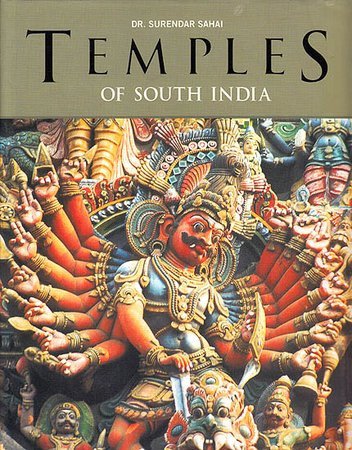

The illustrations, several of which have never been published before, go to complete this important publication on Chola art. It is much to be hoped that Shri S.R. Balasubrahmanyam will shortly be able to cover the rest of the Chola period and thus conclude the series as a fitting tribute to the devoutness and aesthetic sensibilities of a great dynasty of South Indian monarchs. Of Parantaka I in the Anbil Plates of Sundara Chola it is said, “the earth had a good king and poetic art a proper seat and skill in the fine arts found a common shelter”. This patronage of the arts is indeed the proud heritage of all the Chola kings.

Camp: New Delhi

27th March, 1971

Karl Khandalavala

Editor, Lalit Kala and Chairman, Lalit

Kala Akademy, New Delhi