Complete works of Swami Abhedananda

by Swami Prajnanananda | 1967 | 318,120 words

Swami Abhedananda was one of the direct disciples of Sri Ramakrishna Paramhamsa and a spiritual brother of Swami Vivekananda. He deals with the subject of spiritual unfoldment purely from the yogic standpoint. These discourses represent a study of the Social, Religious, Cultural, Educational and Political aspects of India. Swami Abhedananda says t...

Chapter 4 - Political Institutions of India

Those who have studied the history of the civilization of ancient India are well acquainted with the fact that the Hindus were highly civilized at least five thousand years ago. The earliest records of Hindu civilization are to be found in the Rig Veda, the oldest Scriptures of the world, and in other writings of the vedic period. From these sources we learn, as was shown in the last lecture, that the Indo-Aryans of those prehistoric times organized their society into tour general classes: Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Sudras, according to their colour, qualifications, and professions. The Brahmins were entrusted with literary and priestly duties; while the Kshatriyas were those who devoted their energy to protect the country against invaders, to govern the land, and to look after the welfare and safety of all other classes. Industry, trade, commerce, agriculture, and the various duties of a commercial life were undertaken by those who were known as the Vaishyas or the merchant class; and the Sudras belonged to the serving class.

The vedic writings also tell us that the Indo-Aryans of those days cultivated the land with ploughs, used oxen and horses in the field, undertook irrigation by means of canals, and knew the use of wells and reservoirs for drinking as well as for irrigation. Various kinds of industry, trade and commerce, as also the existence of current money—like pieces of gold of a certain fixed value, for use in buying and selling are mentioned in the Rig Veda. The Indo-Aryans, we read, furthermore, were continually engaged in fighting against the non-Aryan aboriginal tribes who were the original inhabitants of India, and remnants of whom are still to be found in some parts among the hill tribes, just as you find today in some of the original inhabitants of America in certain parts of this country. In these battles with hostile tribes “the (Aryan) warriors used not only armour and helmets, but also protecting armour for the shoulder, probably shields. They used javelins and battle-axes, and sharp-edged swords, besides bows and arrows. All the weapons of war known elsewhere in ancient times were known in India four thousand years ago. Drums assembled men in battle, banners led them on in compact masses, and the use of war horses and chariots was well-known. Tame elephants were in use too”.[1]

The Rig Veda contains numerous allusions which show that the use of iron, gold, and of other metals was known to the Hindus. Armours worn in war are mentioned in Book I, 140, 10; in II, 39, 4; in IV, 53, 2, as in various other places; while the javelin, in Sanskrit Rishti, and the battle-axe Bashi in Sanskrit, are mentioned in the Rig Veda, V, 52, 6, and 57, 2. Three thousand mailed warriors are spoken of in the same Veda, VI, 27, 6; and sharp-edged swords are described in VI, 47, 10. That the arrowheads were made of iron is shown in Book VI, 75, 15: “We extol the arrow which is poisoned whose face is iron”, and in the next book (83, 1) we read: “When the battle is nigh and the warrior marches in his armour, he appears like the cloud”.

It was by ceaseless fighting that the ancient Indo-Aryans protected themselves in their newly-conquered country, extended the limits of cultivation, and built new towns and villages. This interminable warring and fighting forced the conquering Aryan tribes to organize their political and military institutions. Thus the political institutions of the Hindus are as old as their civilization. They divided the country into various kingdoms, principalities, and chiefships, each enjoying perfect autonomy. At the head of each province or kingdom was a Hindu chief or governor, who was called a Rajah, which means ‘prince’ or ‘king’. These Rajahs were absolutely independent of one another. They entertained friendly relations with the Rajahs of other neighbouring provinces, and sometimes they were jealous of each other. But there never was a universal sovereignty over the whole of India, like that of the great autocrat of Russia, although there were powerful monarchs and emperors to whom other kings, chiefs, and governors of states acknowledged subordination and paid tribute. Their autonomy, however, was never sacrificed. Their alliances generally bore the character of confederacies, or federal unions, and not that of feudal baronies subject to a ruling chief; and under no circumstances were the servile duties of the feudal barons of Europe exacted from the weaker Rajahs or governors. The bond between them was of the feeblest kind, and easily broke at every favourable opportunity. In the vedic period, there were many such emperors or Chakravartins, as they were called in Sanskrit. In the Ramayana, we read that Rama was the emperor of Ayodhya (modern Oudh), and his power extended all over northern and southern India as far down as Ceylon. From the Mahabharata, which contains the history of the Hindus who lived as early as 1400 b.c.,we learn that Yudhishthira became the emperor of India after the battle of Kurukshetra. His successors, Parikshit, Janmejaya, and many others, were known as emperors. These emperors had a number of Rajahs under them, who paid allegiance and tribute to them. But their bond could break at any time for very insignificant causes.

When Alexander the Great invaded India, there was on the throne the most powerful Buddhist emperor, Chandra Gupta, whose capital was Pataliputra, modem Patna, on the river Ganges. His grandson was Asoka, who lived in 260 b.c. and became the most celebrated emperor of those days. He was like Constantine the Great among the Buddhists. He made Buddhism the state religion of India; he sent missionaries from Siberia to Ceylon, from China to Egypt, and made treaties with kings of foreign countries. One of the edicts of Asoka, which were written during his lifetime, says that he made treaties with five Greek kings who were his contemporaries, namely, Antiochus of Syria, Ptolemaos of Egypt, Antigonus of Macedon, Magus of Cyrene, and Alexander of Epiros; and he sent missionaries to those places, as far as Alexandria, to preach the Gospel of Buddha.

Alexander the Great, however, invaded only the northwestern corner of India, and defeated in one battle some of the hill-tribes, but afterwards, when he heard of the power and strength of Chandra Gupta, he withdrew his troops and returned to Greece.’ His successor, Seleucus, sent the Greek ambassador Megasthenes, who lived for several years at the court of this great emperor. From the accounts of Megasthenes, which are the most authentic historical records that we can gather from an outsider, we learn many facts about the political insti-tutions of the Hindus as witnessed by a foreigner during the fourth century b.c. Megasthenes left a valuable record of the actual work of administration as observed by him. He says: “Those who have charge of the city are divided into six bodies of five each. The members of the first look after everything relating to the industrial arts. Those of the second attend to the entertainment of foreigners. To those they assign lodgings, and they keep watch over their modes of life by means of those persons whom they give to them for assistants. They escort them on the way when they leave the country, or, in the event of their dying, forward their property to their relatives. They take care of them when they are sick, if they die, bury them. The third body consists of those who inquire when and how births and deaths occur, with a view not only of levying a tax, but also in order that births and deaths among both high and low may not escape the cognizance of government. The fourth class superintends trade and commerce. Its members have charge of weights and measures, and see that the products in their season are sold by public notice. No one is allowed to deal in more than one kind of commodity unless he pays a double tax. The fifth class supervises manufactured articles, which they sell by public notice. What is new is sold separately from what is old, and there is a fine for mixing the two together. The sixth and last class consists of those who collect the tenths of the prices of the articles sold”.

The military officers “also consist of six divisions, with five members in each. One division is appointed to co-operate with the admiral of the fleet; another with the superintendent of the bullock-trains which are used for transporting engines of war, food for the soliders, provender for the cattle, and other military requisites.... The third division has charge of the foot-soldiers, the fourth of the horses, the fifth of the warchariots, and the sixth of the elephants.”

In addition to the military and municipal officers, there was a third class whose duty was to superintend agriculture, irrigation, forests, and the general work of administration in rural districts. “Some superintend the rivers, measure the land, as is done in Egypt, and inspect the sluices by which water is let out from the main canals into their branches, so that every one may have an equal supply of it. The same persons have charge also of the huntsmen, and are entrusted with the power of rewarding or punishing them according to their deserts. They collect the taxes, and superintend the occupations connected with land, as those of the woodcutters, the carpenters, the blacksmiths, and the miners. They construct roads, and at every ten stadia set up a pillar to show the by-roads and distances”.[2]

The laws of war among the Hindus were more humane than among the other nations of the world, and Megasthenes mentions this fact. All these Rajahs governed their country in accordance with their laws and for the welfare of their people, and what accounts we get from Megasthenes are exactly the same as those we read in Manu, Apastamba, and other Sanskrit law-books of ancient time. Regarding the military law, or the laws of war, the Hindu lawgiver Apastamba says: “The Aryans forbid the slaughter of those who have laid down their arms, of those who beg for mercy with flying hair or joined hands, and of fugitives” (II, 5, 10, II.), “Let him not fight with those who are in fear, intoxicated, insane or out of their minds, nor with those who have lost their armour, nor with women, infants, aged men, and Brahmins” (Bodhayana, I, 10, 18, II). “The wives of slain soldiers were always provided for” (Vasishtha XIX, 20.). Megasthenes says: “For whereas among other nations it is usual, in the contests of war, to ravage the soil, and thus to reduce it to an uncultivated waste, among the Indians, on the contrary, by whom husbandmen are regarded as a class that is sacred and inviolable, the tillers of the soil, even when battle is raging in the neighbourhood, are undisturbed by any sense of danger.... Besides, they (the warriors) never ravage an enemy’s land with fire nor cut down its trees. They never use the conquered as slaves”.[3]

The duties of the king, according to the lawgiver Manu, were “to protect his subjects, to deal impartial justice, and to punish the wrongdoer.” (VII, 12, 16.) These were the three principal duties. “Drinking, gambling and licentiousness, and hunting were the most pernicious faults of the king” (VII, 50.). The private life of kings is described by Manu thus: “The king should rise in the last watch of the night, and, having performed his personal purification and devotional exercises, he should enter the hall of audience in the morning. There he should gratify all subjects who come to see him, and, having dismissed them, he should take counsel with his ministers in a private chamber” (VII, 145-147.). “When the consultation is over, then he is ready to take care of his physical needs, meals, and so on”. But his first duty is to give an audience to his subjects and to gratify their demands. “In the afternoon, the king should review his army, inspect his fighting-men, his chariots, animals, and weapons, and then perform his twilight devotions. After this he should give audience to his secret spies and hear private reports” (VII, 221-225.). “The king was always assisted by his council of seven or eight ministers,” as we read in the laws of Manu (VII, 54-63), “who were versed in sciences, skilled in the use of weapons, and descended from noble and well-tried families. Such ministers used to advise the king in matters of peace and war, revenue and religious gifts. The king also employed suitable persons for the collecting of revenue, and in mines, manufactories, and store-houses; and he employed ambassadors for carrying on negotiations with rulers”. For the protection of villages and towns, separate officers were appointed. The king appointed a lord over each village, over ten villages, lords of twenty, of a hundred, and of a thousand villages; and these lords were not merely governors, but they used to check crime and protect the villages. These were the special duties of these special officers. They were like superintendents. Similarly, each town had its superintendent of all affairs, who personally inspected the work of all officials and got secret information about their behavior and private character, because the Hindu law says: “The servants of the king, who are appointed to protect the people, generally become knaves, who seize the property of others; let him protect his subjects against such men” (Manu, VII, 115-123.). From this you will see that, in ancient times, government officials used to become knaves, as they do now in a highly civilized country like America. Think of the time when this law was written,—centuries before Christ!

The income of the state from the royal demesnes was supplemented by taxes. Manu fixes an income-tax of two per cent on cattle and gold. The land revenue varied from one-sixth to one-eighth or one-twelfth of the crops,[4] and this was much less than the land-revenue tax under British rule. Under the Hindu rule, the king was strictly prohibited from exacting excessive taxation. He was allowed to take one-sixteenth part of the price made on butter, earthen vessels and stone wares, and might exact a day’s service in each month from artisans, mechanics, and other working-people; that is one day in a month these people would give their service free. Of course, they were maintained by the king, that is, they were fed by the king at that time; and with this institution, in ancient times, they could erect wonderful buildings, palaces, and monuments for public use, which now they cannot do because the cost is so great.

All these and others law s regarding administration and taxation show that an advanced system of government prevailed in India before the beginning of the Christian era. Megasthenes, who lived in India in the fourth century before Christ, as also the Chinese travellers, Fa Hian, who visited India about 400 a.d., and Houen Tsang, who came to India about 630 a.d. and resided there for nearly fifteen years, spoke in the highest terms of praise of the government and administration of the Hindu Rajahs. Frequently we hear that the Hindus were so badly governed at that time that they had no peace or justice and were constantly engaged in fighting; but these witnesses of other nations, who came from other countries and lived in India, left records which speak differently. They do not cite one single instance of a people being ground down by taxes, or harassed by the arbitrary acts of kings, or ruined by famines, plagues, or internecine wars. On the contrary, they say: “The people were happy, prosperous, enjoying peace and justice. Agriculture flourished, the fine arts were cultivated”. Houen Tsang, in his diary, which has been translated into English by Samuel Beal, wrote thus, describing the administration of India: “As the administration of the country is conducted on benign principles, the executive is simple... The private demesnes of the crown are divided into four principal parts: the first is for carrying out the affairs of state and providing sacrificial offerings: the second is for providing subsidies for the ministers and chief officers of state; the third is for rewarding men of distinguished ability; and the fourth is for charity to religious bodies, whereby the field of merit is cultivated. In this way the taxes on the people are light, and the personal service required of them is moderate. Each one keeps his own worldly goods in peace, and all till the ground for their subsistence. Those who cultivate the royal estates pay a sixth part of the produce as tribute.

The merchants who engage in commerce come and go in carrying out their transactions. The river passages and the road barriers are open on payment of a small toll. When the public works require it, labour is exacted, but paid for. The payment is in strict proportion to the work done.

“The military guard the frontiers, or go out to punish the refractory. They also mount guard at night round the palace. The soldiers are levied according to the requirements of the service; they are promised certain payments, and are publicly enrolled. The governors, ministers, magistrates, and officials have each a portion of land assigned to them for their personal support”.

Houen Tsang also says that tributary kings from China sent hostages to Kanishka, the great Buddhist emperor, who reigned in Kashmir (north-western India) about 78 a.d., and he treated them with special favour, and set apart for their residence that portion of the country which afterwards was named Chinapati. The Chinese introduced the pear and the peach into India, “wherefore the peach is called Chinani and the pear is called Chinarajaputra(son of the Chinese monarch)”.

Such political conditions existed in India from the time of Megasthenes down to Houen Tsang, that means from nearly the fourth century b.c. to the seventh century a.d. Besides these, the most remarkable feature of the political organization of ancient India was the village community and municipal institutions. This village community was called ‘panchayat’, or committee of five. There was originally a committee of five, then afterwards it was increased to twelve. Each community formed itself into an independent little republic, which managed its own affairs and governed itself, but which was bound to the central government by the regular payment of an assessment or tax on the produce. Each district, again, was divided into territories which were governed by the village community, or ‘panchayat’. Under this self-government by community, every individual member enjoyed absolute political freedom and independence. Each had full voice in the government. This government by panchayat is described in Manu and in other law-books of ancient India, and it has always existed among the Hindus. The people first elected their head-man, or president, who was a kind of mayor, and who was paid by a fixed proportion of land. He was the chairman of the village or town council, and used to call regular meetings. The next important officer of the community was the notary', or local attorney, who transacted the village business and kept an account of the land and produce, the rents and assessments. Then there was a Brahmin priest, a village schoolmaster, a barber, a carpenter, a blacksmith, a cowman, a shoe-maker, a potter, a washerman, a druggist, an oilman, the watchman, and the sweeper. These made up the village community. These members discussed and managed the whole affairs of the territory.

From the time of Manu, or from at least four hundred years before Christ, this form of municipal institution has existed in India, undisturbed by foreign invasions and political convulsions, internal wars, famine, plague, or earthquake. Sir Monier Monier Williams says: “And here I may observe that no circumstance in the history of India is more worthy of investigation than the antiquity and permanence of her village and municipal institutions. The importance of the study lies in the light thereby thrown on the parcelling out of rural society into autonomous institutions, like those of our own English parishes, wherever Aryan races have occupied the soil in Asia or in Europe. The Indian village or township, meaning thereby not merely a collection of houses forming a village or town, but a division of territory, perhaps three or four miles or more in extent, with its careful distribution of fixed occupations for the common good, with its intertwining and inter-dependence of individual, family, and communal interests, with its provision for political independence and autonomy, is the original type, the first germ, of all the divisions of rural and civic society in mediaeval and modem Europe. It has existed almost unaltered since the description of its organization in Manu’s code, two or three centuries before the Christian era. It has survived all the religious, political, and physical convulsions from which India has suffered from time immemorial. Invader after invader has ravaged the country with fire and sword,... but the simple, self-contained Indian township has preserved its constitution intact, its customs, precedents, and peculiar institutions, unchanged and unchangeable, amid all other changes”.[5]

During the Mohammedan rule of six hundred years, all these political institutions of the Hindus remained unaltered. They were never modified or disturbed. The Hindu villagers did not know that they were governed by the Mohammedans. The throne was occupied by a Mohammedan or Mogul emperor, to whom the native Rajahs and queens paid tribute, but beyond that they had no obligation; they were quite independent. Each Rajah had his own laws, his own court, and his own separate administration. The government of the country according to the Hindu system has always been continued in the native states. Even at the present time there are native states governed by Hindu Rajahs where you will still find this kind of government. The Mohammedans never gained absolute control over the whole of India. Before the advent of the British rule, the administration of justice, the repression of crime, and other functions of the police, the collection of cesses and taxes, were all carried out by the government of the village community. Today in British India this self-government of the Hindus has been destroyed by the short-sighted policy of the British autocrats, and its place has been given to a most costly system of judicial administration, unparalleled in the history of the world. They talk about English justice. Of course there is justice in English government, but it is very expensive and one-sided. Indians have justice among Indians, but if an Indian’s rights are outraged by a European he cannot hope for similar justice. The poorer classes, furthermore, cannot pay for justice under any conditions; it is too expensive. The present oppression of the police and the cruelty of revenue collectors under British management have already driven the masses to the verge of absolute despair and rebellion.

Many people in this country think that England conquered India by force of arms, but history tells us that some English merchants first came to India to trade at the time when the Mohammedan power was in its decline, and the Hindus were fighting against the Mohammedans to throw off their yoke and reestablish Hindu power upon the throne of Delhi. At this time of anarchy and revolution, these British traders, under the name of the East India Company, took the side of the Mohammedans and gained the confidence of the last of the Mogul[6] emperors, who was then merely a titular sovereign. He had lost all power; nobody obeyed him. As a return for what he had received from the East India Company and as favour to Lord Clive, this last of the Mogul emperors, in 1765, gave a charter making the East India Company of British traders the Dewan, or administrators, of Bengal. Though the Great Mogul had no real power to do such a thing, still, as long as he was the titular sovereign of India, his charter gave the East India Company a legal status in the country. The officers of the Company held that charter in their hands wherever they went. Lord Clive himself, in his letter to the Court of Directors from Calcutta dated September 30, 1765, writes: “The assistance which the Great Moghal had received from our arms and treasury made him readily bestow this grant upon the Company”. “I mean the Dewanee, which is the superintendency of all the lands and the collection of all the revenues of the provinces of Bengal, Behar, and Orissa”. These three provinces first came into the hands of the East India Company, and at that period the revenue from them was enormous. Lord Clive writes again: “Your revenues, by means of this acquisition, will, as near as I can judge, not fall far short, for the ensuing year, of 250 lakhs of Sicca Rupees, including your former possession of Burdwan, etc. Hereafter they will at least amount to twenty or thirty lakhs more. Your civil and military expenses in time of peace can never exceed sixty lakhs of Rupees; the Nawab’s allowances are already reduced to forty-two lakhs, and the tribute to the king (the Great Moghal) at twenty-six; so that there will be remaining a clear gain to the Company of 122 lakhs of Sicca Rupees, or £1,650,900 sterling.”[7] “An annual remittance of over a million and a half sterling was to be made from a subject country to the shareholders (of the East India Company) in England.”[8]

This was the beginning of British empire in India. That annual remittance has now increased and swelled to nearly thirty million pounds sterling. “The scheme administration introduced by Clive was a sort of dual government. The collection of revenues was still made for the (Mohammedan) Nawab’s exchequer; justice was still administered by the Nawab’s officers; and all transactions were covered by the mask of the Nawab’s authority. But the East India Company, the real masters of the country, derived all the profits; and the Company’s servants practised unbounded tyranny for their own gain, overawing the Nawab’s servants, and converting his tribunals of justice into instruments for the prosecution of their own purposes.”[9] It is a long story; time will not permit me to describe the harrowing tales of the foul and treacherous methods which were adopted by the unworthy representatives of the English people, under the name of the East India Company, to secure for their motherland a market-place for her trade and commerce, and to bring benefit and prosperity to the British nation, which was at that time the poorest nation in Europe. Those who have read the impeachment of Warren Hastings by Burke, as also impartial students of the history of the East India Company, are already acquainted with the brutal policy of the Company, which has ruined the most prosperous country of India. Zemindars were dispossessed of their hereditary rights, their lands were let to the highest bidder by public auction, trade and manufacture were destroyed by monopoly and coercion, prohibitive duties were charged on manufactured articles, etc.

Terrible famines began for the first time with the British rule in India. In 1770 there was a terrible famine in the district of Purneah, in Bengal, in which above one-third of the population died of starvation; but the revenue from land-tax was exacted with such tyranny and oppression that even during that famine it was larger than in previous years. On the 9th of May, 1770, the Calcutta Council wrote to the Court of Directors: “The famine which has ensued, the mortality, the beggary, exceed all description. Above one-third of the inhabitants have perished in the once plentiful province of Purneah, and in other parts the misery is equal.” On the 12th of February, 1771, they wrote: “Notwithstanding the great severity of the late famine, and the great reduction of the people thereby, some increase has been made in the settlements (of taxes) both of the Bengal and the Behar provinces for the present year.”[10] Mr. Dutt says in his Economic History of India: “Famines in India are directly due to a deficiency in the annual rainfall; but the intensity of such famines and the loss of lives caused by them are largely due to the chronic poverty of the people. If the people were generally in a prosperous condition, they could make up for local failure of crops by purchases from neighbouring provinces, and there would be no loss of life. But when the people are absolutely resourceless, they cannot buy from surrounding tracts, and they perish in hundreds of thousands, or in millions, whenever there is a local failure of crops.”[11]

The reports of the Indian Famine Commissions of 1880 and 1898 show that between 1860 and 1900, that is, within forty years, there were ten widespread famines in India. In 1860 a famine broke out in Northern India and the loss of life was estimated at 2,00,000, but was probably much larger; in 1866 a famine in Orissa carried off one-third of the population, or about a million people; in 1869 there was another famine in Northern India, during which at least 1,200,000 people died; in 1874 Bengal was visited by famine, but the land-tax in this province is light and is permanently settled; the people are therefore comparatively prosperous and resourceful, and there was no loss of life from this famine. The land-tax of Madras, on the contrary, is heavy and is enhanced from time to time, and the people are poor and resourceless; when, therefore, a famine broke out there in 1877 and five millions perished. A third famine in Northern India in 1878 cost the lives of 1,250,000 people; and during the famine of 1889 in Madras and Orissa the loss of life was very severe, but no official figures are available. In 1892, again, there was a famine in Madras, Bengal, Burma, and Rajputana, causing a heavy loss of life in Madras but none in Bengal. In 1897 famine swept over all Northern India, Bengal, Burma, Madras, and Bombay. The number of people on relief works alone rose to three millions in the worst months. Deaths were prevented in Bengal and elsewhere, but in the Central Provinces the death rate rose from an average of thirty-three per mile to sixty-nine per mile during the year. The famine of 1900 in the Punjab, Rajputana, the Central Provinces, and Bombay was the most widespread ever known in India. The number of persons relieved rose to six millions in the worst months. In Bombay, in the famine camps, so Sir A. P. Macdonnell, President of the Famine Commission, reported, the people “died like flies.” “The results of the three famines within the last ten years (1891-1901), and of the increasing poverty of the people, are shown in the census taken in March, 1901. The population of India has remained stationary during the last ten years. There is a slight increase in Bengal, Madras, and Northern India, while there is an actual decrease of some millions in Bombay, the Central Provinces, and the Native States affected by recent famines. In other words, the population of India to-day is less by some thirty millions than it would have been if the nominal increase of one per cent per annum had taken place during these ten years.”[12]

Warren Hastings, who had succeeded Clive as Governor of Bengal, was made first Governor-General in 1772. Pitt’s India Bill became a law in 1784. It removed the administration of the East India Company from the hands of directors and placed it under the control of the crown, thus compelling some reforms. Lord Cornwallis then became the successor of Warren Hastings. The policy of all of the Governor-Generals under the East India Company was to extend the British territory, to absorb the Native States by declaring war on the slightest pretence, to increase the revenue, and to drain the country of her resources. “The people of India have no votes, and are not even represented in the Executive Councils of India. They have no voice in the matter of taxation or of expenditure. They have no share in the work of adjusting the finances of India. Taxation exceeds all reasonable limits in India, and the proceeds of the taxation are not all spent in India. A large sum, estimated between twenty and thirty millions in English money, is annually drained from India to this country (England). The disastrous results of this annual drain have been described by many English writers and administrators throughout the century which has just closed”.[13] Sir Thomas Munro, for some time Governor of Madras, after forty years’ experience in India, wrote in 1824: “They (natives of India) have no share in making laws for themselves; little in administering them, except in very subordinate offices; they can rise to no high station, civil or military; they are everywhere regarded as an inferior race, and more often as vassals or servants than as the ancient owners and masters of the country.... All the civil and military offices of any importance are now held by Europeans, whose savings go to their own country”. Mr. Frederick John Shore, of the Bengal Civil Service, wrote in 1837: “The halcyon days of India are over; she has been drained of a large proportion of the wealth she once possessed, and her energies have been cramped by a sordid system of misrule, to which the interests of millions have been sacrificed for the benefit of the few”. Professor H. H. Wilson, the noted English historian, also says of the annual drain from India: “Its transfer to England is an abstraction of Indian capital for which no equivalent is given; it is an exhausting drain upon the country, the issue of which is paid by no reflux; it is an extraction of the life-blood from the veins of national industry, which no subsequent introduction of nourishment is furnished to restore”. John Sullivan, at one time a Member of the Government of Madras and President of the Board of Revenue, writes thus in one of his reports: “As to the complaints which the people of India have to make of the present fiscal system, I do not conceive that it is the amount, altogether, that they have to complain of. I think that they have rather to complain of the application of that amount. Under their own dynasties, all the revenue that was collected in the country was spent in the country; but under our rule, a large proportion of the revenue is annually drained away, and without any return being made for it; this drain has been going on now for sixty or seventy years, and it is rather increasing than the reverse.... Our system acts very much like a sponge, drawing up all the good things from the banks of the Ganges, and squeezing them down on the banks of the Thames.... They (the people of India) have no voice whatever in imposing the taxes which they are called upon to pay, no voice in framing the laws which they are bound to obey, no real share in the administration of their own country; and they are denied those rights from the insolent and insulting pretext that they are wanting in mental and moral qualifications for the discharge of such duties”.[14]

The British administrators, in the first part of the nineteenth century, did all they could to promote English industries at the sacrifice of Indian industries; for the policy of English administration in India is shaped, not by statesmen and philosophers, but by merchants, traders, and manufacturers, who are the voters of Great Britain. British manufactures were forced into India through the agency of the Company’s Governor-General and commercial residents, while Indian manufactures were shut out from England by prohibitive tariffs, as the table in the next page will show.

“Petitions were vainly presented to the House of Commons against these unjust and enormous duties on the import of Indian manufactures into England. One petition against the duties on sugar and spirits was signed by some four hundred European and Indian merchants,”[15] and it was rejected by the British Government in England. The policy of England was to make Great Britain independent of foreign countries for the raw material upon which her valuable manufactures depend, and to make India the producer of raw materials for English manufactories. The German economist, Frederick List, said: “Had they sanctioned free importation into England of Indian goods, the English manufactories would have come to a stand.”[16] Thus, within fifty years, India was reduced from the state of manufacturing to that of an agricultural country.

Cotton and silk fabrics, shawls and woolen fabrics, sugar, tobacco, rum, dyes, saltpetre, coffee, tea, steel, gold, iron, copper, coal, timber, opium, and salt,—all these, and grains of all kinds, India had traded with other nations, both Asiatic and European; but, under the pretence of free trade, England has now compelled the Hindus to receive the manufactured products of England free of duty, and has imposed prohibitive duties on Indian manufactures imported to England. No Indian industry of any kind has been encouraged by the British Government during the last one hundred and fifty years. And no less than two hundred and thirty-five articles were subjected to internal duties under the East India Company. Section 6 of the Cotton Duties Act of 1896 runs thus: “There shall be levied and collected at every mill in British India, upon all cotton goods produced in such mill, a duty at the rate of 3| per centum on the value of such goods”. And Mr. Dutt, in commenting upon this Act, says: “As an instance of fiscal injustice, the Indian Act of 1896 is unexampled in any civilized country in modern times. Most civilized governments protect their home industries by prohibitive duties on foreign goods. The most thorough of Free Trade Governments do not excise home manufactures when imposing a moderate customs duty on imported goods for the purposes of revenue. In India, where an infant industry required protection, even according to the maxims of John Stuart Mill, no protection has ever been given. Moderate customs, levied for the purposes of revenue only, were sacrificed in 1879 and 1882. Home-manufactured cotton goods, which were supposed to compete with imported goods, were excised in 1894. And home goods which did not compete with, foreign goods were excised in 1896. Such is the manner in which the interests of an unrepresented nation are sacrificed”.[17] This will give you a rough idea of how India has prospered in her economic condition during British rule.

A special law still exists under the English Government to provide labourers for the cultivation of tea in Assam. “A dark stain is cast on this industry by what is known as the ‘slave-law’ of India. Ignorant men and women, once induced to sign a contract, are forced to work in the gardens of Assam during the term indicated in the contract. They are arrested, punished, and restored to their masters if they attempt to run away; and they are tied to their work under penal laws such as govern no other form of labour in India. Hateful cases of fraud, coercion, and kidnapping, for securing these labourers, have been revealed in the criminal courts of Bengal, and occasional acts of outrage on the men and women thus recruited have stained the history of tea-gardens in Assam. Responsible and high administrators have desired a repeal of the penal laws, and have recommended that the tea-gardens should obtain workers from the teeming labour markets of India under the ordinary laws of demand and supply. But the influence of capitalists is strong; and no Indian Secretary of State or Indian Viceroy has yet ventured to repeal these penal laws, and to abolish the system of semi-slavery which still exists in India”.[18]

Now let us see what is the present political condition of the Indian people: “The East India Company’s trade was abolished in 1833, and the Company was abolished in 1858, but their policy remains. Their capital was paid off by loans, which were made into an Indian debt, on which interest is paid from Indian taxes. The empire was transferred from the Company to the Crown, but the people of India paid the purchasemoney”.[19] In 1858 the public debt was seventy million pounds, which had been piled up by the East India Company during the one hundred years of their rule in India; while they were drawing tribute from India, financially an unjust tribute, exceeding 150 millions, not counting interest. Besides this, they had charged India with the cost of the wars in China, Afghanistan, and in other foreign countries. India, therefore, in reality owed nothing at the close of the Company’s rule. Her Public Debt was a myth. On the contrary, there was a balance of over 100 millions in her favour out of the money that had been drawn from her. The administration of the Crown doubled this Public Debt in nineteen years, bringing it up to 139 million pounds in 1877, when the Queen became Empress of India. Over 40 million sterling of this represented the cost of the Mutiny wars, which was thrown on the revenues of India. India was also made to pay a large contribution to the cost of the Abyssinian war of 1867. In 1900 the debt amounted to 224 million sterling. The construction of railways by Guaranteed Companies or by the State, beyond the pressing needs of India and beyond her resources, was largely responsible for this increase. It was also largely due to the Afghan wars of 1878 and 1897.

India pays interest on this debt, which annually increases. Besides this, she pays for all the officers, civil and military, and a huge standing army, pensions of officers, and even the cost of the India Building in London, as well as the salary of every menial servant in that house. For 1901-2 the total expenditure charged against revenue was £71,394,282 out of which £17, 368,655 was spent in England as Home Charges, not including the pay of European officers in India, saved and remitted to England. These charges were as follows:

1. Interest on Debt and Management of Debt — £8,052,410

2. Cost of Mail Service, Telegraph Lines, etc. charged to India — 227,288

3. Railways, State, and Guaranteed (Interest and Annuities) — 6,416,373

4. Public Works (Absentee Allowances, etc.) — 51,214

5. Marine Charges (including H. M. Ships in Indian Seas) — 178,502

6. Military Charges (including pensions) — 2,945,614

7. Civil Charges (including Secretary of State’s Establishment, Cooper’s Hill College, Pensions, etc.) — 2,435,370

8. Stores (including those for Defence Works) — 2,057,934

Total — £17,368,655

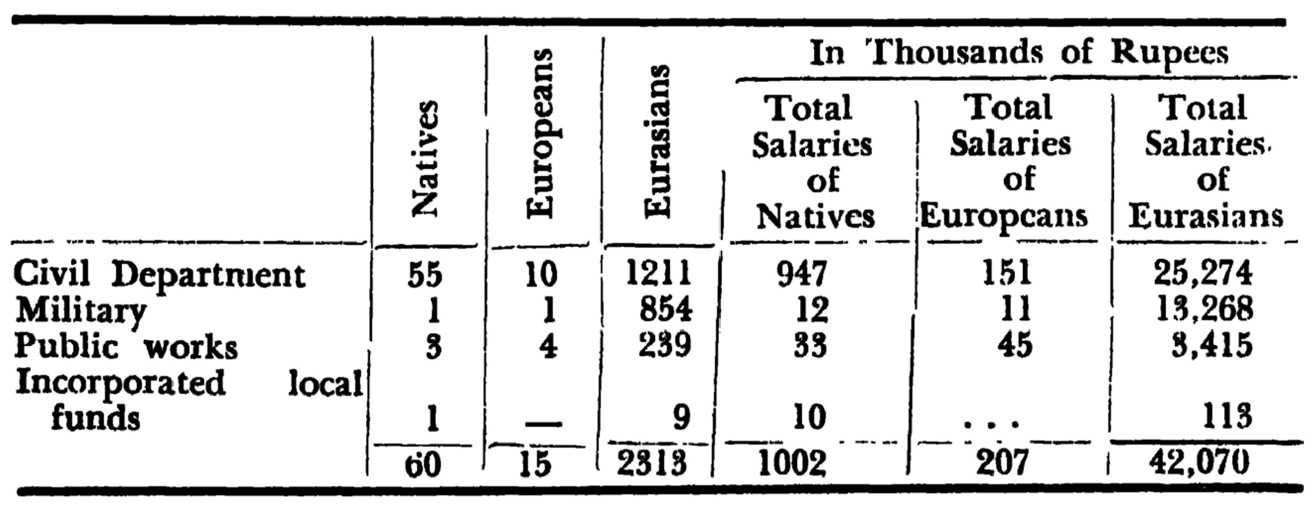

The following, again, is a comparative table of salaries paid out:

Besides these, 105 officers drawing Rs. 10,000 a year or more are employed by the railway companies; they are all Europeans, and their salaries amount to 16 lakhs and 28 thousand rupees (about $542,667). Among the officers, who are paid between Rs. 5000 and Rs. 10,000 a year, we find 421 natives in the civil department as against 1207 Europeans and 96 Eurasians. In the military department 25 natives are employed and 1699 Europeans and 22 Eurasians; while, in the Department of Public Works, there are 85 natives, as against 549 Europeans and 3 Eurasians.

Mr. Alfred Webb (late M.P.), who has studied the subject with care, says: “In charges for the India Office (in London); for recruiting (in Great Britain, for soldiers to serve in India); for civil and military pensions (to men now living in England, who were formerly in the Indian service); for pay and allowances on furloughs (to men on visits to England); for private remittances and consignments (from India to England); for interest on Indian Debt (paid to parties in England); and for interest on railways and other works (paid to shareholders in England),—there is annually drawn from India, and spent in the United Kingdom, a sum calculated at from £25,000,000 to £30,000,000” (between $125,000,000 and $150,000,000).

It would have been bad enough if this drain had continued for a few years, or even for one year, but it began with the day when India came under England’s power and has been kept up ever since. Of this Mr. Brooks Adams writes: “Very soon after Plassey (fought in 1757) the Bengal plunder began to arrive in London, and the effect seems to have been almost instantaneous.... Possibly since the world began, no investment has ever yielded the profit reaped from the Indian plunder”.[20] The stream of wealth ruthlessly drawn from the conquered people of India, and poured from Indian treasuries into English banks, between Plassey and Waterloo (fifty-seven years, has been variously calculated at from £500,000,000 to £1,000,000,000. The Westminister Gazette of London, April 24, 1900, estimates the drain from India to England, during the closing twenty-five years of the nineteenth century, to have been £500,000,000 ($2,500,000,000). It would be impossible to believe these enormous figures if they were not taken from authentic records. Can we wonder that India today is so impoverished? Could any nation withstand so merciless and unceasing a drain upon its resources?

The popular belief is that England has sunk her enormous capital in the development of India; but the truth is, that England has not spent a cent in governing India (compare this with the Colonial Governments). The Indian Government means today the government of a bureaucracy, which includes the Viceroy and the Members of the Executive Council, the Commander-in-Chief, the Military Member, the Home Member, the Public Works Member, the Finance Member, and the Legal Member. The people are not represented in this Council; their agriculture, their landed interests, their trades and industries, are not represented; there is not, and never has been, a single Indian member in the Council. The members are high English officials, who draw large salaries and get pensions for life after their service is over.

Then in each large Indian province there is a Legislative Council, and some of the members of these smaller Councils are elected under the Act of 1892. The principal function of the Legislative Council is legislation. In theory it exercises control over finance, but in practice the budget is submitted to the autocracy merely for criticism; the representatives, however, can exercise no control over its being passed.

The Council consists of twenty-five members, four of whom are Indians, recommended by certain constituencies but appointed by the Viceroy. He has the power to appoint any one he pleases. He calls them elected, for the purpose of argument. The four Indians sit at one end of the table and the Englishmen at the other end. Beginning with the Indians, each one reads the speech he has prepared in order of seniority, each speech being prepared without knowledge of what the others will say, consequently without reference to what they have said. There is no real discussion. The Viceroy may turn its course as he pleases. The representatives cannot produce any impression on the Council, nor can they divide the Council or shape the decision in any way. It is indeed no representation of the natives in the proper sense of the term.

The Viceroy of India is under the orders of the Indian Secretary of State, who is a member of the English Cabinet. The Secretary of State lives in England, six thousand miles away from the governed people. He is assisted by a Council of ten retired Anglo-Indian officials, who seek the interest of their own nation. The whole system is, as Sir William Hunter calls it, an “oligarchy” which does not represent the people.

The Government of India is as despotic as it is in Russia, because three hundred millions of people who are governed have neither voice nor vote in the government. The interest of the British nation is the first aim of the present system of government. People pay heavy taxes of all kinds, and that is all. The government sends out expeditions to Sudan, Egypt, China, Tibet, and other places outside of India, and then the poor people of India are forced to pay the enormous cost of these expeditions, amounting to millions of dollars.[21] The land-tax, income-tax, and various kinds of taxes are higher than in any other civilized part of the world. “In India the State virtually interferes with the accumulation of wealth from the soil, intercepts the incomes and gains of the tillers, and generally adds to its land-revenue demand at each recurring settlement, leaving the cultivators permanently poor. In England, in Germany, in the United States, in France, and in other countries, the State widens the income of the people, extends their markets, opens out new sources of wealth, identifies itself with the nation, grows richer with the nation. In India the State has fostered no new industries and revived no old industries for the people; on the other hand, it intervenes at each recurring land settlement to take what it considers its share out of the produce of the soil.”[22]

“But the land-tax levied by the British Government is not only excessive, but, what is worse, it is fluctuating and uncertain in many provinces. In England, the land-tax was between one shilling and four shillings in the pound, i.e., between 5 and 20 per cent. of the rental, during a hundred years before 1798, when it was made perpetual and redeemable by William Pitt. In Bengal the land-tax was fixed at over 90 per cent, of the rental, and in Northern India at over 80 per cent, of the rental, between 1793 and 1822”.[23]

Today the masses of people in India live on from two to five cents a day and support their families with these earnings. Expecting to have their grievances removed by the government, they have been agitating for the last twenty years by calling annual public meetings and special public meetings, where the best classes of educated people have been represented. Although the Indian Government has spared no pains to stop all such agitations, still the people have been passing resolutions and sending them to the Viceroy and to the Secretary of State. Not one single word of encouragement has ever come from the despotic rulers, who are determined to follow the steps of the Russians in their methods of administration. Indeed, Sir Henry Cotton says: “Even the Russian Government, which we are accustomed to look upon as the ideal of autocracy, is not such a typical autocracy as the Government of India”.

Ambitious, unsympathetic young civilians go out to India for a few years to exploit the country, satisfy their greed and self-interest, and return home to live like lords, drawing upon the taxes of the impoverished millions. I will give you an illustration of Lord Curzon’s administration. Lord Curzon was the most unpopular Viceroy ever in India. His policy was one of interference and distrust. He is no believer in free institutions or in national aspirations. He took away the freedom of the press, which was steadily gaining in weight and importance, by passing the Official Secrets Act. The policy of his administration was to keep all civil as well as all military movements of the government secret. He sent expedition to Tibet. He wasted the resources of the country on the vain show and pomposity of the Durbar while millions were dying of famine and plague. He condemned the patriotic and national spirit of the Indians, and lastly he carried out the Roman policy of divide and rule by partitioning the Province of Bengal, simply to cripple the unity of the educated natives, as also of seventy millions of inhabitants. All these and many acts he carried out with such despotism and high-handedness, against the unanimous opinion of seventy million people, that they were driven to boycott all English goods and manufactures. The fire of boycott has spread all over the country, like wildfire in a forest. The people have unanimously appealed to the Viceroy and to the Secretary of State again and again, but all the higher officials of India and England have turned deaf ears to them. It is to be hoped that this boycott will bring the English autocrats and despots to their senses.

The people of India are loyal and peace-loving, but they are discontented and impoverished after carrying for one hundred and fifty years the burden of an unsympathetic alien government. There would have been continuous rebellion and mutiny had they not so long depended upon passive resistance with the expectation that some day the famous proclamation of the late Queen Victoria would be carried into effect.

On the morrow of the dark mutiny Queen Victoria proclaimed:

“We desire no extension of our present territorial possessions; and, while we will permit no aggression upon our dominions or our rights to be attempted with impunity, we shall sanction no encroachment on those of others. We shall respect the rights, dignity, and honour of Native Princes as our own; and we desire that they, as well as our own subjects, should enjoy that prosperity and social advancement which can only be secured by internal peace and good government.

“We hold ourselves bound to the Natives of our Indian territories by the same obligations of duty which bind us to all our subjects, and those obligations, by the blessing of Almighty God, we shall faithfully and conscientiously fulfil.

“Firmly relying ourselves on the truth of Christianity, and acknowledging with gratitude the solace of religion, we disclaim alike the right and the desire to impose our convictions on any of our subjects. We declare it to be our royal will and pleasure that none be anywise favoured, none molested or disquieted, by reason of their religious faith and observances, but that all shall alike enjoy the equal and impartial protection of the law; and we do strictly charge and enjoin all those who may be in authority under us that they abstain from all interference with the religious belief and worship of any of our subjects, on pain of our highest displeasure.

“And it is our further will that, so far as may be, our subjects, of whatever race or creed, be freely and impartially admitted to offices in our service, the duties of which they may be qualified, by their education, ability, and integrity, duly to perform.”

(Lord Curzon, however, openly declared that all Indians were disqualified by reason of their race.)

This proclamation was repeated by King Edward VII on the day of his coronation. But have the Anglo-Indian bureaucracy shown any desire to do the things which were promised by the late Empress and the present Emperor, King Edward? No.

People have now organized themselves, have sent delegates to England and America, and have awakened to the truth of what John Stuart Mill said: “The government of a people by itself has a meaning and a reality, but such a thing as government of one people by another does not and cannot exist. One people may keep another for its own use, a place to make money in, a human cattle farm for the profit of its own inhabitants”.

The natives of India are now determined to stand on their own feet, but it is a hard problem for an enslaved nation to raise their heads while the dominant sword of a powerful alien government is held close to their necks. If the people of America wish to know what would have been the condition of the United States under British rule, let them look at the political and economic condition of the people of India today.

Well has it been said by Mr. Reddy, an English friend of India: “England, through her missionaries, offered the people of India thrones of gold in another world, but refused them a simple chair in this world”.[24]

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Cf. Civilization in Ancient India, Vol. I, p. 58.

[2]:

Vide MacCrindle’s Translation.

[3]:

Ibid.

[4]:

Vide Civilization in Ancient India, Vol. II, p. 102.

[5]:

Cf. Brahminism and Hinduism, p. 455.

[6]:

Mogul, Moghal, Mughal, etc. these are different spellings in different books.

[7]:

House of Commons Third Report, 1773, Appendix, pp. 391-398.

[8]:

Economic History of British India, p. 39.

[9]:

Cf. Economic History of British India, p. 42.

[10]:

Extracts from India Office Records quoted in Hunter’s Annals of Rural Bengal, 1868, pp. 21, 399.

[11]:

Ibid. 51.

[12]:

Cf. R. C. Dutt: Indian Famines, p. 2.

[13]:

Cf. by R. C. Dutt: Indian Famines, p. 10.

[14]:

Cf. Report of the Select Committee, p. 402.

[15]:

Cf. Economic History of India, p. 294

[16]:

Cf. The National System of Political Economy, p. 42.

[17]:

Cf. India in the Victorian Age, p. 543.

[18]:

Cf. India in the Victorian Age, p. 352.

[19]:

Cf. Economic History of India, p. xii.

[20]:

Cf. Law of Civilization and Decay, pp. 259-264.

[21]:

Vide India in the Victorian Age, p. 604.

[22]:

Cf. Economic History of British India, p. xi.

[23]:

Ibid. p. ix.

[24]:

Cf. India, Oct. 13, 1905.

FAQ (frequently asked questions):

Which keywords occur in this article of Volume 2?

The most relevant definitions are: India, Bengal, Manu, Aryan, Madras, Megasthenes; since these occur the most in “political institutions of india” of volume 2. There are a total of 63 unique keywords found in this section mentioned 294 times.

Can I buy a print edition of this article as contained in Volume 2?

Yes! The print edition of the Complete works of Swami Abhedananda contains the English discourse “Political Institutions of India” of Volume 2 and can be bought on the main page. The author is Swami Prajnanananda and the latest edition is from 1994.