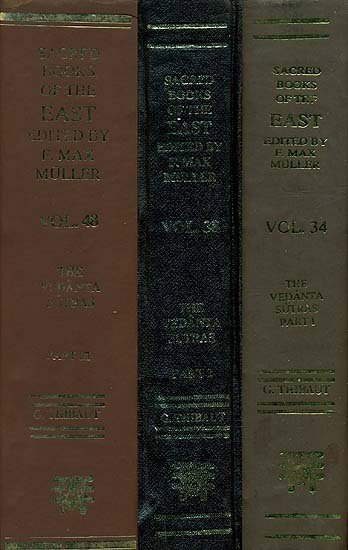

Brahma Sutras (Ramanuja)

by George Thibaut | 1904 | 275,953 words | ISBN-10: 8120801350 | ISBN-13: 9788120801356

The English translation of the Brahma Sutras (also, Vedanta Sutras) with commentary by Ramanuja (known as the Sri Bhasya). The Brahmasutra expounds the essential philosophy of the Upanishads which, primarily revolving around the knowledge of Brahman and Atman, represents the foundation of Vedanta. Ramanjua’s interpretation of these sutras from a V...

Sutra 3.4.2

2. On account of (the Self) standing in a complementary relation, they are arthavādas, as in other cases; thus Jaimini opines.

What has been said as to Scripture intimating that a beneficial result is realised through the meditations by themselves is untenable. For texts such as 'he who knows Brahman reaches the Highest' do not teach that the highest aim of man is attained through knowledge; their purport rather is to inculcate knowledge of Truth on the part of a Self which is the agent in works prescribed. Knowledge, therefore, stands in a complementary relation to sacrificial works, in so far as it imparts to the acting Self a certain mystic purification; and the texts which declare special results of knowledge, therefore, must be taken as mere arthavādas. 'As in the case of other things; so Jaimini thinks,' i.e. as Jaimini holds that in the case of substances, qualities, and so on, the scriptural declaration of results is of the nature of arthavāda.—But it has been shown before that the Vedānta-texts represent as the object to be attained, by those desirous of Release, on the basis of the knowledge imparted by them, something different from the individual Self engaged in action; cp. on this point Sū. I, 1, 15; I, 3, 5; I, 2, 3; I, 3, 18. And Sū. II, 1, 22 and others have refuted the view that Brahman is to be considered as non-different from the personal soul, because in texts such as 'thou art that' it is exhibited in co-ordination with the latter. And other Sūtras have proved that Brahman must, on the basis of numerous scriptural texts, be recognised as the inner Self of all things material and immaterial. How then can it be said that the Vedānta-texts merely mean to give instruction as to the true nature of the active individual soul, and that hence all meditation is merely subservient to sacrificial works?—On the strength of numerous inferential marks, the Pūrvapakshin replies, which prove that in the Vedānta-texts all meditation is really viewed as subordinate to knowledge, and of the declarations of co-ordination of Brahman and the individual soul (which must be taken to imply that the two are essentially of the same nature), we cannot help forming the conclusion that the real purport of the Vedānta-texts is to tell us of the true nature of the individual soul in so far as different from its body.—But, again it is objected, the agent is connected no less with ordinary worldly works than with works enjoined by the Veda, and hence is not invariably connected with sacrifices (i.e. works of the latter type); it cannot, therefore, be maintained that meditations on the part of the agent necessarily connect themselves with sacrifices in so far as they effect a purification of the sacrificer’s mind!—There is a difference, the Pūrvapakshin rejoins. Worldly works can proceed also if the agent is non-different from the body; while an agent is qualified for sacred works only in so far as he is different from the body, and of an eternal non-changing nature. Meditations, therefore, properly connect themselves with sacrifices, in so far as they teach that the agent really is of that latter nature. We thus adhere to the conclusion that meditations are constituents of sacrificial actions, and hence are of no advantage by themselves.—But what then are those inferential marks which, as you say, fully prove that the Vedānta-texts aim at setting forth the nature of the individual soul?—To this the next Sūtra replies.