Brahma Sutras (Ramanuja)

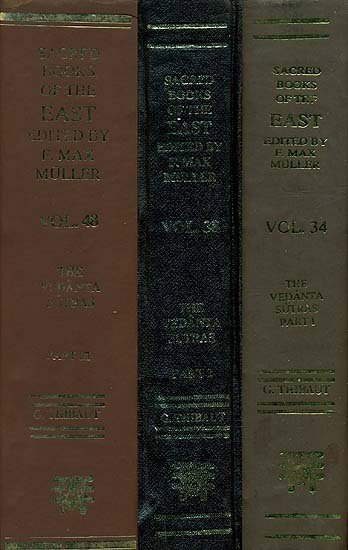

by George Thibaut | 1904 | 275,953 words | ISBN-10: 8120801350 | ISBN-13: 9788120801356

The English translation of the Brahma Sutras (also, Vedanta Sutras) with commentary by Ramanuja (known as the Sri Bhasya). The Brahmasutra expounds the essential philosophy of the Upanishads which, primarily revolving around the knowledge of Brahman and Atman, represents the foundation of Vedanta. Ramanjua’s interpretation of these sutras from a V...

Sutra 1.4.10

10. And on account of the teaching of formation (i.e. creation) there is no contradiction; as in the case of the honey.

The 'and' expresses disposal of a doubt that had arisen. There is no contradiction between the Prakṛti being ajā and originating from light. On account of instruction being given about the formation (kalpana), i.e. creation of the world. This interpretation of 'kalpana' is in agreement with the use of the verb kḷip in the text, 'as formerly the creator made (akalpayat) sun and moon.'

In our text the śloka 'from that the Lord of Māyā creates all this' gives instruction about the creation of the world. From that, i.e. from matter in its subtle causal state when it is not yet divided, the Lord of all creates the entire Universe. From this statement about creation we understand that Prakṛti exists in a twofold state according as it is either cause or effect. During a pralaya it unites itself with Brahman and abides in its subtle state, without any distinction of names and forms; it then is called the 'Unevolved,' and by other similar names. At the time of creation, on the other hand, there reveal themselves in Prakṛti Goodness and the other guṇas, it divides itself according to names and forms, and then is called the 'Evolved,' and so on, and, transforming itself into fire, water, and earth, it appears as red, white, and black. In its causal condition it is ajā, i.e. unborn, in its effected condition it is 'caused by light, i.e. Brahman'; hence there is no contradiction. The case is analogous to that of the 'honey.' The sun in his causal state is one only, but in his effected state the Lord makes him into honey in so far namely as he then, for the purpose of enjoyment on the part of the Vasus and other gods, is the abode of nectar brought about by sacrificial works to be learned from the Ṛk and the other Vedas; and further makes him to rise and to set. And between these two conditions there is no contradiction. This is declared in the Madhuvidyā (Kh. Up. III), from 'The sun is indeed the honey of the Devas,' down to 'when from thence he has risen upwards he neither rises nor sets; being one he stands in the centre'—'one' here means 'of one nature.'—The conclusion therefore is that the Śvetāsvatara mantra under discussion refers to Prakṛti as having her Self in Brahman, not to the Prakṛti assumed by the Sāṅkhyas.

Others, however, are of opinion that the one ajā of which the mantra speaks has for its characteristics light, water, and earth. To them we address the following questions. Do you mean that by what the text speaks of as an ajā, consisting of fire, water, and earth, we have to understand those three elements only; or Brahman in the form of those three elements; or some power or principle which is the cause of the three elements? The first alternative is in conflict with the circumstance that, while fire, water, and earth are several things, the text explicitly refers to one Ajā. Nor may it be urged that fire, water, and earth, although several, become one, by being made tripartite (Ch. Up. VI, 3, 3); for this making them tripartite, does not take away their being several; the text clearly showing that each several element becomes tripartite, 'Let me make each of these three divine beings tripartite.'—The second alternative again divides itself into two alternatives. Is the one ajā Brahman in so far as having passed over into fire, water, and earth; or Brahman in so far as abiding within itself and not passing over into effects? The former alternative is excluded by the consideration that it does not remove plurality (which cannot be reconciled with the one ajā). The second alternative is contradicted by the text calling that ajā red, white, and black; and moreover Brahman viewed as abiding within itself cannot be characterised by fire, water, and earth. On the third alternative it has to be assumed that the text denotes by the term 'ajā' the three elements, and that on this basis there is imagined a causal condition of these elements; but better than this assumption it evidently is to accept the term 'ajā' as directly denoting the causal state of those three elements as known from scripture.

Nor can we admit the contention that the term 'ajā' is meant to teach that Prakṛti should metaphorically be viewed as a she-goat; for such a view would be altogether purposeless. Where—in the passage 'Know the Self to be him who drives in the chariot'—the body, and so on, are compared to a chariot, and so on, the object is to set forth the means of attaining Brahman; where the sun is compared to honey, the object is to illustrate the enjoyment of the Vasus and other gods; but what similar object could possibly be attained by directing us to view Prakṛti as a goat? Such a metaphorical view would in fact be not merely useless; it would be downright irrational. Prakṛti is a non-intelligent principle, the causal substance of the entire material Universe, and constituting the means for the experience of pleasure and pain, and for the final release, of all intelligent souls which are connected with it from all eternity. Now it would be simply contrary to good sense, metaphorically to transfer to Prakṛti such as described the nature of a she-goat—which is a sentient being that gives birth to very few creatures only, enters only occasionally into connexion with others, is of small use only, is not the cause of herself being abandoned by others, and is capable of abandoning those connected with her. Nor does it recommend itself to take the word ajā. (understood to mean 'she-goat') in a sense different from that in which we understand the term 'aja' which occurs twice in the same mantra.—Let then all three terms be taken in the same metaphorical sense (aja meaning he-goat).—It would be altogether senseless, we reply, to compare the soul which absolutely dissociates itself from Prakṛti ('Another aja leaves her after having enjoyed her') to a he-goat which is able to enter again into connexion with what he has abandoned, or with anything else.—Here terminates the adhikaraṇa of 'the cup.'