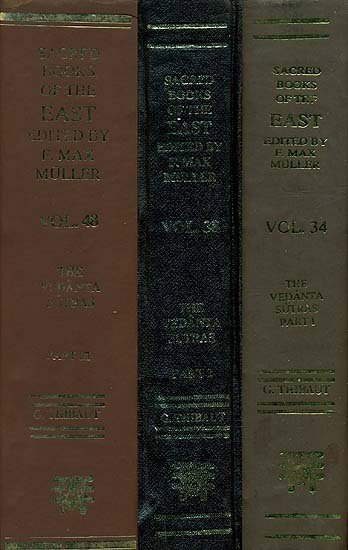

Brahma Sutras (Ramanuja)

by George Thibaut | 1904 | 275,953 words | ISBN-10: 8120801350 | ISBN-13: 9788120801356

The English translation of the Brahma Sutras (also, Vedanta Sutras) with commentary by Ramanuja (known as the Sri Bhasya). The Brahmasutra expounds the essential philosophy of the Upanishads which, primarily revolving around the knowledge of Brahman and Atman, represents the foundation of Vedanta. Ramanjua’s interpretation of these sutras from a V...

Sutra 1.2.10

10. And on account of the topic of the whole section.

Moreover the highest Brahman constitutes the topic of the entire section. Cp. 'The wise who knows the Self as great and omnipresent does not grieve' (Ka. Up. I, 2, 22); 'That Self cannot be gained by the Veda, nor by understanding, nor by much learning. He whom the Self chooses, by him the Self can be gained; the Self chooses him as his own' (I, 2, 23).—Moreover, the clause (forming part of the text under discussion),'Who knows him (i.e. the being which constitutes the topic of the section) where he is?' clearly shows that we have to recognise here the Self of which it had previously been said that it is hard to know unless it assists us with its grace.

To this conclusion a new objection presents itself.—Further on in the same Upanishad (I, 3, 1) we meet with the following text: 'There are two, drinking their reward in the world of their own works, entered into the cave, dwelling on the highest summit; those who know Brahman call them shade and light, likewise those householders who perform the Trinakiketa-sacrifice.' Now this text clearly refers to the individual soul which enjoys the reward of its works, together with an associate coupled to it. And this associate is either the vital breath, or the organ of knowledge (buddhi). For the drinking of 'ṛta' is the enjoyment of the fruit of works, and such enjoyment does not suit the highest Self. The buddhi, or the vital breath, on the other hand, which are instruments of the enjoying embodied soul, may somehow be brought into connexion with the enjoyment of the fruit of works. As the text is thus seen to refer to the embodied soul coupled with some associate, we infer, on the ground of the two texts belonging to one section, that also the 'eater' described in the former text is none other than the individual soul.—To this objection the next Sūtra replies.