Brahma Sutras (Ramanuja)

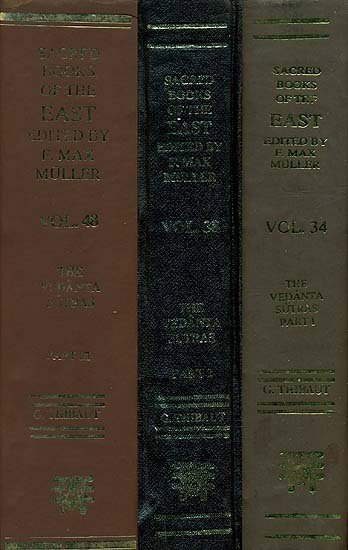

by George Thibaut | 1904 | 275,953 words | ISBN-10: 8120801350 | ISBN-13: 9788120801356

The English translation of the Brahma Sutras (also, Vedanta Sutras) with commentary by Ramanuja (known as the Sri Bhasya). The Brahmasutra expounds the essential philosophy of the Upanishads which, primarily revolving around the knowledge of Brahman and Atman, represents the foundation of Vedanta. Ramanjua’s interpretation of these sutras from a V...

Sutra 1.1.32

32. If it be said (that Brahman is not meant) on account of characteristic marks of the individual soul and the chief vital air; we say no, on account of the threefoldness of meditation; on account of (such threefold meditation) being met (in other texts also); and on account of (such threefold meditation) being appropriate here (also).

An objection is raised. 'Let none try to find out what speech is, let him know the speaker'; 'I slew the three-headed son of Tvashṭṛ; I delivered the Arunmukhas, the devotees, to the wolves'; these passages state characteristic marks of an individual soul (viz. the god Indra).—'As long as Prāṇa dwells in this body, so long there is life'; 'Prāṇa alone is the conscious Self, and having laid hold of this body, it makes it rise up.'—These passages again mention characteristic attributes of the chief vital air. Hence there is here no 'multitude of attributes belonging to the Self.'—The latter part of the Sūtra refutes this objection. The highest Self is called by these different terms in order to teach threefoldness of devout meditation; viz. meditation on Brahman in itself as the cause of the entire world; on Brahman as having for its body the totality of enjoying (individual) souls; and on Brahman as having for its body the objects and means of enjoyment.—This threefold meditation on Brahman, moreover, is met with also in other chapters of the sacred text. Passages such as 'The True, knowledge, infinite is Brahman,' 'Bliss is Brahman,' dwell on Brahman in itself. Passages again such as 'Having created that he entered into it. Having entered it he became sat and tyat, defined and undefined,' etc. (Taitt. Up. II, 6), represent Brahman as having for its body the individual souls and inanimate nature. Hence, in the chapter under discussion also, this threefold view of Brahman is quite appropriate. Where to particular individual beings such as Hiraṇyagarbha, and so on, or to particular inanimate things such as prakṛti, and so on, there are attributed qualities especially belonging—to the highest Self; or where with words denoting such persons and things there are co-ordinated terms denoting the highest Self, the intention of the texts is to convey the idea of the highest Self being the inner Self of all such persons and things.—The settled conclusion, therefore, is that the being designated as Indra and Prāṇa is other than an individual soul, viz. the highest Self.